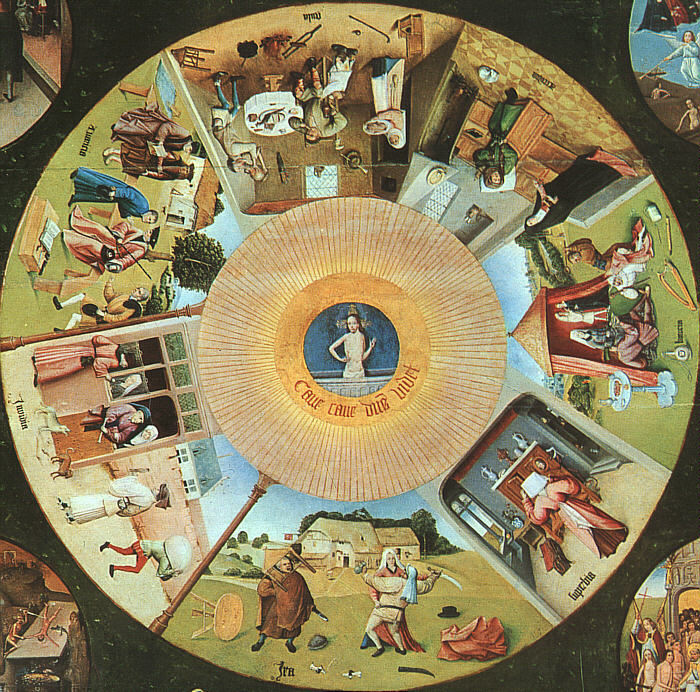

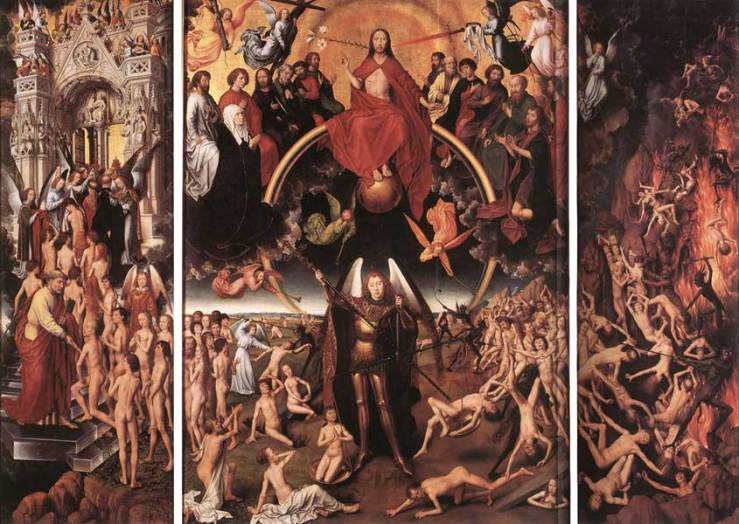

In William Gaddis‘s massive first novel, The Recognitions, Wyatt Gwyon forges paintings by master artists like Hieronymous Bosch, Hugo van der Goes, and Hans Memling. To be more accurate, Wyatt creates new paintings that perfectly replicate not just the style of the old masters, but also the spirit. After aging the pictures, he forges the artist’s signature, and at that point, the painting is no longer an original by Wyatt, but a “new” old original by a long-dead genius. The paintings of the particular artists that Wyatt counterfeits are instructive in understanding, or at least in hoping to understand how The Recognitions works. The paintings of Bosch, Memling, or Dierick Bouts function as highly-allusive tableaux, semiotic constructions that wed religion and mythology to art, genius, and a certain spectacular horror, and, as such, resist any hope of a complete and thorough analysis. Can you imagine, for example, trying to catalog and explain all of the discrete images in Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights? And then, after creating such a catalog, explaining the intricate relationships between the different parts? You couldn’t, and Gaddis’s novel is the same way. I’ve finished the first of the novel’s three parts, 277 of 956 pages, and I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that the Gaddis has structured the novel as a triptych. The first part, like Bosch’s painting, The Seven Deadly Sins, is comprised of seven sections.

Early in The Recognitions, teenage Wyatt copies The Seven Deadly Sins–his father owns the original, a painted table top he purchased in Europe. Wyatt replaces the original with his own and gets away with this strange crime–no small feat considering the genius of his father, the Rev. Gwyon, a New England priest who, after the death of his wife at sea, comes to reject the austere puritanism of his order and embrace (much to the consternation of his dwindling congregation) a pluralistic religious world view. In one of many stunning passages centering on Gwyon and religion, the congregation is “stirred with indignant discomfort after listening to the familiar story of virgin birth on December twenty-fifth, mutilation and resurrection, to find they had been attending, not Christ, but Bacchus, Osiris, Krishna, Buddha, Adonis, Marduk, Balder, Attis, Amphion, or Quetzalcoatl.” This series of substitutions enacts a chain of recognitions, and, in a sense, compartmentalizes much of the thematic material of the novel: What is it to be a hero, a redeemer, a savior? What is originality, and how does one recognize it? Who originates whom? What does it mean to create? How is art separate from religion? Clearly, these are not simple questions, and The Recognitions is not a simple book.

In order to pose (and perhaps offer varying answers to) these questions, Gaddis employs daring, richly detailed prose, larded with esoteric (and not so esoteric) references to mythology, religion, art, music, and literature. Like the discrete sections of Bosch’s Sins, each of the chapters of the first section of The Recognitions has its own distinct idiom, comportment, and rhythm; yet, even as Gaddis’s approaches seem discontinuous from chapter to chapter, these coalesce to a larger picture.

The first chapter is the best first chapter of any book I can remember reading in recent years. It tells the story of Rev. Gwyon looking for solace in the Catholic monasteries of Spain after his wife’s death at sea under the clumsy hands of a fugitive counterfeiter posing as a doctor (already, the book posits the inherent dangers of forgery, even as it complicates those dangers by asking who isn’t in some sense a phony). There’s a beautiful line Gaddis treads in the first chapter between pain, despair, and melancholy and caustic humor, as Gwyon slowly realizes the false limits of his religion. The chapter continues to tell the story of young Wyatt, growing up under the stern care of his puritanical Aunt May, whose religious attitude is confounded by the increasingly erratic behavior of Wyatt’s often-absent father. While deathly ill, Wyatt teaches himself to paint by copying masterworks. He also attempts an original, a painting of his dead mother, but he cannot bear to finish it because, as he tells his father, “There’s something about . . . an unfinished piece of work . . . Where perfection is still possible. Because it’s there, it’s there all the time, all the time you work trying to uncover it.” This problem of originality, of Platonic perfection guides much of the novel’s critique on Modernism.

Wyatt studies but ultimately rejects the ministry, opting instead to become an artist. The second chapter finds him in Paris, attempting to sell his original work. The chapter is a bravura shift into the sounds, sights, and consciousness of another world, another distinct mythology–ex-patriot Paris, Hemingway’s Paris, Woolf’s Paris. Gaddis shows a heavy debt to James Joyce‘s innovations in Ulysses here (and throughout the book, of course), although it would be a mistake to reduce the novel to a mere aping of that great work. Rather, The Recognitions seems to continue that High Modernist project, and, arguably, connect it to the (post)modern work of Pynchon, DeLillo, and David Foster Wallace. (In it’s heavy erudition, numerous allusions, and complex voices, the novel readily recalls both W.G. Sebald and Roberto Bolaño as far as I’m concerned). By the third chapter we find Wyatt married, quite unhappily, producing hack work, copies he lets his boss put his name on. The chapter is painful and often ugly, as we see his marriage disintegrate. In this chapter he meets Recktall Brown, the Mephistophelean business man who will arrange Wyatt’s future career as a counterfeiter of original paintings. As the chapter ends, Wyatt is no longer referred to by his name, a device that continues throughout the rest of part one (and perhaps the whole book). It’s as if he’s lost something intrinsic, some core originality in exchange for the ability to “become” the artist he is emulating. Wyatt now disintegrates into the background of the narrative, and is exchanged for a young Harvard grad named Otto. Otto follows Wyatt around like a puppy, writing down whatever he says, absorbing whatever he can from him, and eventually sleeping with his wife. Otto is the worst kind of poseur; he travels to Central America to finish his play only to lend the mediocre (at best) work some authenticity, or at least buzz. He fakes an injury and cultivates a wild appearance he hopes will give him artistic mystique among the Bohemian Greenwich Villagers he hopes to impress. In the fifth chapter, at an art-party, Otto, and the reader, learn quickly that no one cares about his play–everyone’s busy making their own original art. Gaddis’s evocation of a Village party in the late forties/early fifties here is wonderful, fly-on-the-wall stuff. His rhetoric captures the buzzing musicality of a raucous house party, and even if his mockery of the assembled artists, critics, and wannabes is savage, it’s also loving. Gaddis has an astute ear for the mid-twentieth century, where gossip infiltrates debate on aesthetics, and commercials punctuate classical scores on the radio.

Wyatt (unnamed) returns for the seventh (and longest) chapter of part one. He’s been very successful at his work, although he seems not to care at all for the money he’s making. Instead, he seems obsessed with channeling these ancient masters, for only in this pre-modern world is originality possible. Of course, the levels of irony are confounding here: Wyatt’s only access to originality is to pretend to be another person. The originality of the paintings he creates is subject to the condition that they be not original to him (their creator) but to another. While this attack on Modernity–namely, that originality is impossible–is severe, it’s also worth noting that Gaddis’s writing enacts originality, even as it cobbles together disparate sources. This is what makes the novel such an addictive pleasure to read. While I cannot make any final claims about a novel before finishing it, I will go out on another limb and suggest that those who already own this novel and have not yet made a crack at it for fear of its massive size and allusive structure should go ahead and take it up: it’s dark, erudite, sad, and very, very funny. It’s also not that hard to read, and if the allusions get too dense, there’s always Steven Moore‘s fantastic resource, A Reader’s Guide to William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, now available in its entirety online. Have at it. More when I finish Part II.

me again, and yeah I’ve tried to get so many people to read this damn book, the first time I read it cold, and this time I’d go back and read all the annotations… crazy how, even during a re-read I’d miss some HUGE plot points that were noted in the synopsis… drop me an e-mail if you feel like chatting about it… I’m subscribed to the Gaddis list serve but don’t have much to contribute there as I’m sure it’s all be said there before…

LikeLike

Hi, Biblioklept, I stumbled upon your interesting blog searching for a photo of a Gaddis cover to put on my FB page . . . I’m well into part 2 of The Recognitions and enjoying myself immensely with this massively difficult but rewarding read! Greets from the Netherlands,

Gertrud

LikeLike

I’ve been reading The Recognitions for about two years and whilst it’s undeniably my favourite book I find I can’t read more than about ten pages in any one month. JESUS IT’S GOOD.

LikeLike

Good post…. I appreciated the focus on the painters that Wyatt forges.

“Gaddis shows a heavy debt to James Joyce‘s innovations in Ulysses here”

Fwiw, and you may know this, Gaddis claimed to have not read Ulysses at the time he’d written this book, and was a but put off that people always assumed Joyce was the big influence. He’d’ve said Eliot, among others, instead. (He’d planned to quote the entirety of The Four Quartets, dispersed throughout the text, but apparently abandoned that plan somewhere along the way.)

Also, if you haven’t seen Orson Welles’ F for Fake, you should see it forthwith. Very entertaining documentary, about someone who did the very thing Wyatt does (create new “originals” of paintings by masters).

LikeLike

Hi, Richard,

I wasn’t aware of Gaddis’s comments on Joyce when I wrote this a few years ago, but I’ve since read his deflections (I actually posted them here, for anyone interested: https://biblioklept.org/2012/01/23/william-gaddis-on-james-joyce/ ). (I’m a bit obsessed lately re: JR).

I understand Gaddis’s annoyance (intentional fallacy be damned!), but, even if he *hadn’t* read Ulysses (and it doesn’t matter either way), it seems to me that many (or most) of his readers must have read Joyce, and, in a sense, must have learned to read (or at least been primed to read) by Joyce. But this is speculative.

I saw “F” *years* ago (in college); I have almost no real memory of it, so I’ll make sure to view it again.

LikeLike

Right, I’d actually seen that earlier post of yours (but I guess forgot it was here–everyone seems to be writing about Gaddis all of a sudden these days, so I’m losing track!).

I’m sure you’re right that most of his readers will have read Joyce first, but I think he makes an excellent and true point (which I paraphrase and re-work here) that Joyce rather gets in the way instead of helping. I think it’s the assumption people make that is what’s most galling, as if they’ve captured something meaningful by making the connection. For what it’s worth, I’ve read all of Gaddis (well, the four real novels), and still haven’t read Ulysses (though I have read Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist.

LikeLike

F Is for Fake is, uh, on YouTube. In its entirety (for now?):

LikeLike

[…] wound up distracted not quite half way through, and eventually abandoned the book. I did, however, write about its first third. I will plunder occasionally from that write-up in this riff. Like here: In William Gaddis‘s […]

LikeLike

[…] with writing about J R (which I did here and here) or The Recognitions (which I did here and here), which seems nonsensical because those books are so big and this one is so short. But that’s […]

LikeLike

Hi! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine

Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results.

If you know of any please share. Many thanks!

LikeLike