In his 1994 novel Butterfly Stories, William T. Vollmann explores the intense cost of unrelenting idealism. Butterfly Stories is a tragic-comic bildungsroman centered around the life of a protagonist who is almost certainly a semi-autobiographical stand-in for Vollmann. He’s never named in the text; few of the characters are. Instead, he goes by various appellations: the butterfly boy, the boy who wanted to be a journalist, the journalist, the husband. These names square with the protagonist’s painful idealism. He’s a professional alien, a traveler who reports on all the beautiful ugly poor places we Quiet (Ugly) Americans forget about (or never know of in the first place). The main set piece in Butterfly Stories takes place in Thailand and Cambodia:

Once upon a time a journalist and a photographer set out to whore their way across Asia. They got a New York magazine to pay for it. They each armed themselves with a tube of coll soft K-Y jelly and a box of Trojans. The photographer, who knew such essential Thai phrases as: very beautiful!, how much?, thank you and I’m gonna knock you around! (topsa-lopsa-lei), preferred the extra-strength lubricated, while the journalist selected the non-lubricated with special receptacle end. The journalist never tried the photographer’s condoms because he didn’t even use his own as much as (to be honest) he should have; but the photographer, who tried both, decided that the journalist had really made the right decision from a standpoint of friction and hence sensation; so that is the real moral of this story, and those who don’t want anything but morals need read no further.

I’ve quoted the passage at length because I think it delineates a good deal of Vollmann’s program very quickly: whoring-as-gonzo-journalism, a foreshadowing of the sexual grotesquerie to come, blackly ironic humor, and an uncomfortable gap between protagonist and narrator. It’s that gap between the narrator’s ironic detachment and the journalist’s earnest search for meaning–and love–in a world of violence and prostitution that made the book rewarding for me. However, I suspect many will not enjoy (perhaps even hate) this disconnect. The journalist falls in love with several prostitutes throughout the course of the novel, fixating on a Cambodian girl named Vanna in particular. His obsession with Vanna overcomes him, surpasses any rational course of action, and leads him to divorce his wife back in San Francisco in the hopes of marrying a girl he, over time, can no longer even visualize. In short, idealism tortures the protagonist; he’s in love with the idea of love. Late in the novel, he thinks (his thinking framed by the narrator, of course):

Better not to try anything than to be wicked! — That’s how most people acted, and they were probably right, dying their lumpish lives without collecting more than their share of the general blame; but he’d do whatever he was called to do . . .

And later, hallucinating in one of his STD-fueled fevers, he remembers the bully that tormented him back when he was the butterfly boy: “I’m not afraid of you anymore . . . Because I have someone whose life means more to me than mine.” The protagonist’s unrelentingly romanticized view of self-sacrifice is ultimately a defense mechanism against the world’s (equally unrelenting) Darwinian violence.

Vollmann’s milieu of disease-infested, war-torn, economically depressed lands dramatizes this conflict. The violence of the Khmer Rouge, the depravity of prostitution, and the specter of AIDS underpin the novel, and are never mere props for Vollmann, who places his protagonist in a paradoxically privileged vantage point from which to observe, investigate–or ignore–the atrocities of poverty. The book succeeds because of the tension between the narrator’s judgmental, ironic perspective and the protagonist’s big-hearted but ultimately facile dream of a self-sacrificing love. The narrator sees–and lets us see–the ironic selfishness of the protagonist’s dream to save the world, one prostitute at a time.

Just under 300 pages and larded with the author’s spidery black-ink sketches, Butterfly Stories is one of Vollmann’s shorter and more digestible (if that word may be used) volumes. It is bleakly funny, often depressing, and filled with erudite asides on Nobel prizewinners, transvestites, and the benefits of whiskey. And benadryl. Can’t forget the benadryl. Vollmann has an astounding gift for crafting concrete sentences that burst into blistering abstraction, but he can also drift rather aimlessly at times. Does he have an editor? What other literary writer can put out a book of at least 500 pages every year? Butterfly Stories may be a good start for those interested in Vollmann but daunted by his prolific output. It will also repel many readers with its grotesque depictions of sex, which recall Henry Miller and the best of Charles Bukowksi. I liked it very much. Recommended.

New Vollmann excerpt at Vice magazine’s website:

http://www.viceland.com/int/v17n4/htdocs/they-just-want-to-look-in-the-mirror-397.php

LikeLike

thanks for the tip, tip. will post.

LikeLike

Oh My Gosh. Lil n-gga bigger than gorilla

Cause I’m killing every n-gga that

Try to be on my sh-t

Better cuff your chick if you with her

I can get her

And she accidentally slip fall on my d-ck

Ooops, I said on my d-ck

I aint really mean to say on my d-ck

But since we talking about my d-ck

All of you haters say hi to it

I’m Done

LikeLike

okay.

LikeLike

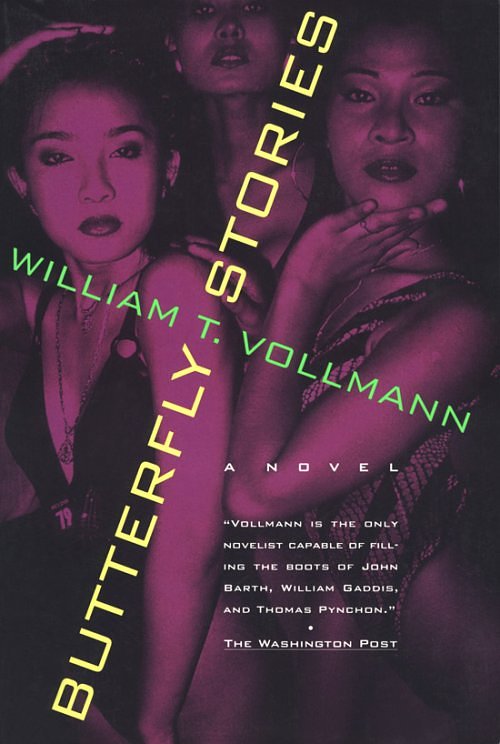

[…] T. Vollmann photographed by Ken Miller during the, uh, adventures chronicled in Butterfly Stories. (Photo […]

LikeLike