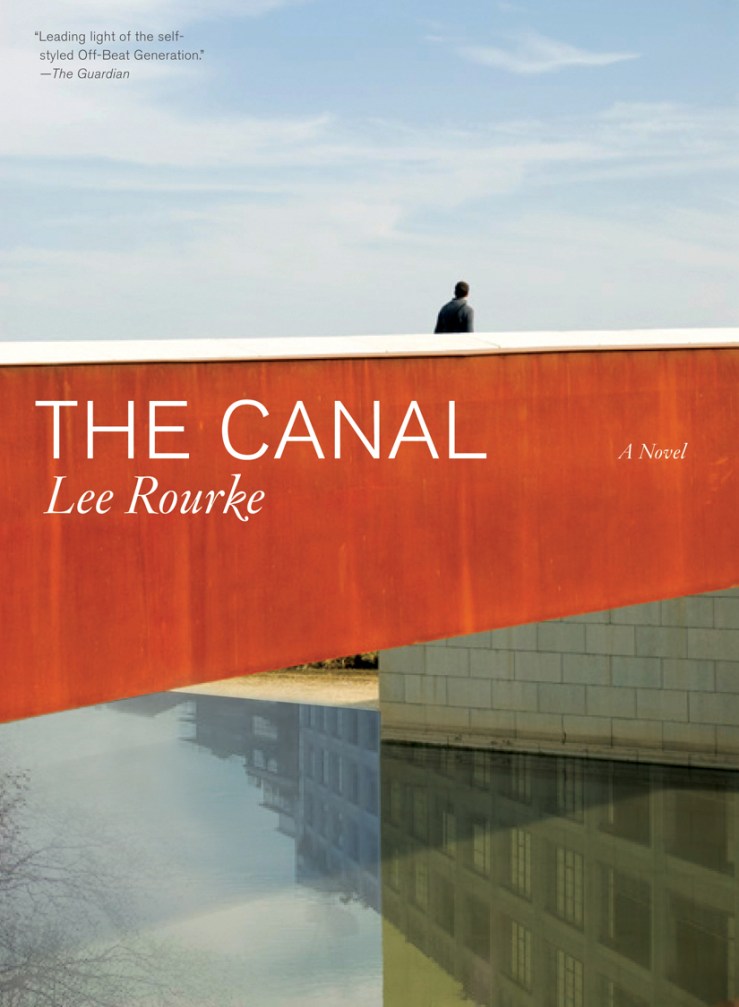

In Lee Rourke’s début novel The Canal, the unnamed narrator quits his job and begins walking to a canal everyday. Why? Out of boredom. At the titular canal, he watches (and describes in banal detail) the geese, swans, and coots that swim in the filthy water. He also keeps one eye on the drudges who go about emailing and faxing in the office building across from the bench on which he sits each day. A strange, icy young woman soon begins sharing the bench with the narrator; in time, she also shares her morbid secrets with him. Complicating the narrator’s paradise of boredom is a gang of youths who terrorize the area with random violence. The novel’s steady pace escalates to frantic tragedy as the narrator’s bored repose gives over to desperate obsession with his erstwhile bench mate and her horrific past.

The Canal takes boredom as its explicit subject. In the second paragraph of the book, the narrator tells us–

Some people think that boredom is a bad thing, that it should be avoided, that we should fill our lives with other stuff in order to keep it at bay. I don’t. I think boredom is a good thing: it shapes us; it moves us. Boredom is powerful. It should never be avoided. In fact, I think boredom should be embraced. It is the power of everyday boredom that compels people to do things–even if that something is nothing.

The canal seems (at first) the right place for the narrator to embrace his boredom, but it soon becomes a space–a “real” space, as the narrator eventually realizes–of transformation and excitement. This space quickly complicates the narrator’s will toward “nothing,” that pull toward nihilism. He’s keenly interested in the various birds that make the canal their home, and his obsessive derision toward the office workers highlights the fact (a fact he doesn’t seem to see) that his apathy is not as pure as he would like it to be. Rather, his “boredom” is a direct response to the apparent meaninglessness of 21st century life in general and, specifically, life in post-Blair London. His horror and fear at the four hoodied teens from a nearby estate (the English equivalent of an American housing project) who insult and attack him is grounded in a relatively conventional morality, one that belies his enduring belief in his own apathy.

The most dramatic challenge to his philosophy of boredom though is his unnamed female foil. Through cryptic, elliptical dialogues he soon becomes a bizarre confessor to her strange sins. Yet she’s remorseless in her unrepentant nihilism. In one conversation she tells him that “There’s nothing left to believe in anywhere. All is fiction. Somehow, we have to invent our own reality. We have to make the unreal real.” This cheerful little aphorism comes after she reveals her empathy for (and sexual attraction to) the perpetrators of the July 7, 2005 suicide bombings in London. Terrorism, particularly the 7/7 attacks and the 9/11 WTC attacks are a major motif of The Canal; the unnamed narrator obsesses about flight (both of airplanes and birds) and dwells on the image of the planes crashing into the towers. Although he never admits it, it seems that both flight and death are possible forms of escape from the very boredom he claims to embrace. At the same time, the violence of terrorism seems part and parcel of his philosophy of boredom–

“It is obvious to me now that most acts of violence are caused by those who are truly bored. And as our world becomes increasingly boring, as the future progresses into a quagmire of nothingness, our world will become increasingly more violent. It is an impulse that controls us. It is an impulse we cannot control.”

And yet the violent acts of the estate youths shock and disgust the narrator. In one of the book’s most stunning passages, he watches them in horror as they destroy a stolen motor scooter and then cast it into the creek while filming the whole business on a cell phone. The scooter upsets the resting birds and becomes one more piece of detritus clogging up the canal–part of the “quagmire of nothingness,” perhaps. Repeatedly in the novel, the narrator wishes that long-overdue dredges will come along to clean the canal, to restore it, an impulse to control the stochastic violence of life that doubles his horror at the teen gang’s violence. In short, despite what he tells us, the narrator cannot embrace his boredom–although he does wish to name it, recognize it, and perhaps treat it.

This treatment comes in the form of the anti-ingenue he meets with daily by the canal. His obsession with her soon gives way to outright stalking. For a man who claims to embrace boredom, he’s awfully interested in her. The narrator’s stalking feeds into the novel’s deft discourse on surveillance in the 21st-century world, where CCTV, mobile phone cameras, and live pictures of spectacular disaster make people feel alternately safe or horrified (or at least alleviate some of their boredom). The narrator’s relationship with the woman tests the bounds of his devotion to boredom and reveals to both him and the novel’s audience that opting out is not always opting out. Rourke uses a quote from Martin Heidegger – “We are suspended in dread” – as an epigraph to the novel; the narrator must learn how to live in that suspension.

What makes The Canal such a remarkable read is watching the disconnect between the narrator’s would-be solution to life-as-state-of-dread (“embrace boredom”) and his actual responses to the effects of boredom in the world around him (literal and figurative waste, violence). Although he seeks to mitigate the pain of his dread and boredom by submitting to it, the novel repeatedly finds him engaging–and resisting–the cruelty and inhumanity he perceives. While parts of The Canal occasionally seem forced or overdetermined, there is much to commend here and the novel clearly suggests Rourke as a rising talent to watch out for. Recommended.

The Canal is available from Melville House on June 15, 2010.

[…] boredom, the writing process, dialogue, foxes, and his new novel The Canal. Read our review of The Canal here. From the interview: Your narrator speaks a lot about his philosophy on boredom. How much of this […]

LikeLike

[…] Bibliokept review CultureCritic review Three Guys One Book review […]

LikeLike

[…] *Το μπλογκ του συγγραφέα, μια συνέντευξή του με δύο αποσπάσματα από το βιβλίο και μια κριτική. […]

LikeLike

I just finished reading The Canal after coming across a very enthusiastic ‘staff pick’ review at a bookstore. While I can’t embrace the novel – I was so bored with the narrator’s flashbacks and some of his descriptions that I had to skim whole passages – this review made me see The Canal in a different light. Maybe reading the book wasn’t entirely a waste of time after all.

LikeLike

Snipe, I didn’t care much for this either and am surprised by the high praise given by reviewers. I didn’t really care for the narrator. I thought he made observations (planes, ducks, swans) but left me with nothing to think about about. He might be bored. I found him boring.

LikeLike

[…] that predates Dostoevsky, Camus, and Bellow, as well as contemporary novels like Lee Rourke’s The Canal and David Foster Wallace’s The Pale […]

LikeLike