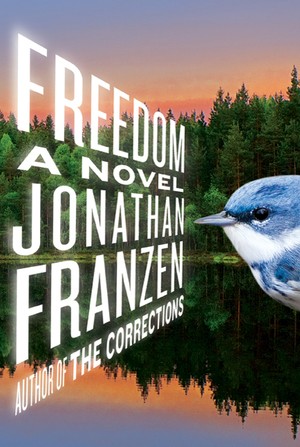

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The reviews have been overwhelmingly positive, even when they can find something to nitpick or quibble with. Obama picked up a copy last week on vacation. In an act of hyperbole so ridiculous as to turn comical, The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones called it “the novel of the century.” (Nevermind that the century isn’t even a decade old). But it’s probably the fact that Franzen appeared on the cover of Time magazine–the first writer in a decade to do so (the last was Stephen King)–that’s caused some professional jealousy and a backlash against Franzen. Again, this is all before the book has been released.

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The reviews have been overwhelmingly positive, even when they can find something to nitpick or quibble with. Obama picked up a copy last week on vacation. In an act of hyperbole so ridiculous as to turn comical, The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones called it “the novel of the century.” (Nevermind that the century isn’t even a decade old). But it’s probably the fact that Franzen appeared on the cover of Time magazine–the first writer in a decade to do so (the last was Stephen King)–that’s caused some professional jealousy and a backlash against Franzen. Again, this is all before the book has been released.

Yes, Franzenfreude. Authors Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner felt the need to speak out against coverage of Freedom, crying foul that their books were not receiving the same critical attention as the “white male literary darling.” You can read an interview with the pair here, where their position seems to be that their work, frequently on the bestseller lists, is dismissed as genre fare. I don’t know Weiner’s stuff but Picoult’s novels strike me as the sort of maudlin crap that get turned into Lifetime movies (which they do). Picoult and Weiner don’t just play the gender card though. No, they also whip out a populist argument, the idea that literary critics ought to give more weight to “what people actually read.” In a series of recent columns on the attention Freedom has garnered, Lorin Stein pointed out that “It has become immensely hard to get a “literary” writer the attention he or she deserves.” (The comments section of Stein’s posts showcase a remarkable debate about just what “literary fiction” is).

Stein is absolutely right of course. (Weiner and Picoult will have to console themselves by sobbing into their piles of money). Franzen’s Freedom has become an opportunity for those who love literary fiction–which might be an endangered species–to call attention to the fact that novels are important, that they can somehow diagnose and analyze the spirit of an age. In his article for The Guardian, William Skidelsky strips the rhetoric away and gets to the point–

Underneath the words “Great American Novelist”, Time‘s strapline ran: “He’s not the richest or most famous. His characters don’t solve mysteries, have magical powers or live in the future. But in his new novel, Jonathan Franzen shows us all the way we live now.” It isn’t hard to unpick the subtext here: “Remember, folks, there’s such a thing as serious literature; it has little to do with Dan Brown or Harry Potter, and these days most of us tend to ignore it, but it’s actually kind of important.”

At The Faster Times, Lincoln Michel is even brassier–

There has always been a segment of the population that does not like it when intelligent artistic work gets praise. These people cry foul when an Academy Award goes to a well-crafted film with limited distribution instead of the latest Hollywood blockbuster, they moan when magazines cover innovative indie musicians instead of the most recent Nickelback CD, and you better believe they can’t stand it when that elitist literary fiction gets awards and coverage that should be reserved for books that people are “actually reading.”

Much of the critical reception of Freedom, then, is more about how the public–the reading public–is to connect with and interact with novels in an age of new media, in an age where some like to pretend the literary novel has lost its relevance, in an age where bozos go around declaring manifestos against novels. While Freedom need not be the novel to “save” the novel, it also shouldn’t be an occasion for backbiting, jealousy, and backlash. Maybe everyone should just calm down and read the damn thing.

[UPDATE: Read our obligatory review of Freedom].

shit’s shit even on judgement day

LikeLike

care to elaborate?

LikeLike

Authors Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner were using the Frazen hoopla to make a greater point about the New York Times. Their complaint was somewhat about Frazen, but also about the bias of the New York Times.

Plenty of people are sick of the Frazen media, even if they enjoy and/or respect his work. Weiner defines it this way: “Schadenfreude is taking pleasure in the pain in others. Franzenfreude is taking pain in the multiple and copious reviews being showered on Jonathan Franzen.” I don’t know if Weiner enjoys or respects Frazen’s work, but her target is the NYTimes and other media. Heck, this post seems bored with the attention even as it strives to put better books in more people’s hands; the “obligatory” review.

So, Picoult and Weiner are having some bitchy fun with Frazen’s press to make a point (and some with Frazen, too); their crime seems to be that they lean more towards being hacks (they admit as much, and also joke about crying in their royalties).

After moving past the sizzle of Frazen, their argument gets interesting. They wonder if authors with less literary ambition, such as Nick Hornby or Carl Hiaasen, get critical cred by being reviewed in the NYTimes while their ilk are left to the bestseller lists only. They also wonder why crime gets plenty of attention while romance gets none, and “chick lit” is dismissed.

These are good questions. I enjoy Hornby a lot, and he’s got talent, but he is not in the category of literary fiction (he touches it at times, but does not settle in long enough, in my view). Slate did a nice piece on it called “Fact Checking the Frazenfreud” (http://www.slate.com/id/2265910/), and it looks like the NYTimes is perpetuating the old bias of the literary canon we all discussed in college.

Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner raise the issue, too, if male writers get an easy pass towards literary cred while women authors have to fight their way out of being pegged as chick lit hacks. Biblioklept’s analysis of Picoult as appropriate for Lifetime is a case in point; he’s not wrong, but Hornby’s “Fever Pitch” and “A Long Way Down” could follow them. Why is one light read trash while another a comic gem? Of course, this all goes into the value we put on women’s stories vs. men’s stories and who controls the presses.

Unfortunately the entire discussion leads to literary fiction retreating into a smaller genre than before. Literary fiction used to simply be fiction, and the good stuff stuck around. I was disappointed with Frazen for his cracks about Oprah, as she had the good taste to pick his book and try and put it in the hands of millions of people so that they could just have a good read. Because of this artificial divide between fiction and literary fiction I find myself poking the latter with a stick before delving in; I can start anything, but while pop fiction is easy to put down and walk away from, bad literary aspirations leave me disappointed.

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughtful response. My problem with Weiner and Picoult’s gripe is that they try to intertwine their populist argument with the idea that there’s a bias against women. So, yeah, Hornby is a great example of “dude lit” (contra “chick lit”) that perhaps gets more of a pass than Picoult, but it seems like they’re quick to forget Toni Morrison, Zadie Smith, Jhumpa Lahiri, and many more less famous female authors who the NYT (and other literary organs) regularly review positively.

When you look at the critical and commercial success of authors like Margaret Atwood and Hilary Mantel–arguably both “genre” writers who prove that genre writing can “transcend” to literary fiction (whatever that might mean–set it aside for a moment, at least)–it seems like Picoult and Weiner’s argument is really a case of sour grapes.

I totally agree with you that what is “good” — what we canonize — is what lasts; the corollary there I suppose is that we don’t really get to see, that even guessing would be difficult, perhaps, as new eras recover lost authors (even Melville was obscure for decades).

I think part of Picoult/Weiner’s gripe is the misguided belief that literary fiction is actually a genre. In an article at the Millions earlier this year (http://www.themillions.com/2010/03/what-about-genre-what-about-horror.html), another genre writer, Peter Straub made the claim explicit:

“Just for beginners, let’s admit that literary fiction is a genre, too, shall we? Expectations guide its readers, that of respect for consensus reality and the poignancy of seemingly ordinary lives, of sensitive character-drawing and vivid scene-painting, of the reversals and conflicts characteristic of the several sub-genres of literary fiction.”

I think Picoult subscribes to this idea and part of her hurt feelings result from it, perhaps — “My themes and subjects might be mawkish, but look, I’m following the conventions!”

True literary fiction–which is just another way of saying art, of recognizing that the work moves beyond mere entertainment, that it performs a judgment or analysis or critique, that it is a type of poem–true literary fiction explodes or dismantles or subverts convention. That’s why pretenders come off so bad, or, as you put it “bad literary aspirations leave me disappointed.” I think specifically now of Eugenides’s *Middlesex*, a novel that strives so hard to be more than entertainment, that buckles under the weight its author keeps piling upon it. It’s badly written (but Upton Sinclair was a bad writer too…).

But I’ve gone tangential.

I have no evidence to support what I’m about to say, but I hope that this discussion leads to more people reading literary fiction–which is expansive, inclusive, and largely unread–and less people griping that their Swedish thrillers and tawdry Movie of the Week fictions are regarded as the stepchildren that they are.

LikeLike

Hey I know I’m wayy late to this party. But what about the fact that 62% of the fictional works reviewed are by men? And 72% of the double reviews?

Scott Lemieux pointed out that “Authors given two reviews for a single book by the Times include the “commercial”* writers Steig Larrson, Scott Turow, Stephen King, John Irving, Nick Hornby, Elmore Leonard, John LeCarre, Christopher Buckley, and Stephen Carter, not to mention John Grisham(!) and Dan Brown(!!). There are some female equivalents, but many fewer, and Bushnell is the only one whose novels seem to clearly fit in a “chick lit” category.”

What about that?

It’s entirely possible that women writers enjoy positive reviews, but that there’s still bias in coverage. Moreover, I think the reason Franzen comes into this discussion is the question of why such crazy declarations. Sam T. compared Franzen to Dickens and Tolstoy and called the book a masterpiece in his first sentence. The estatic gushing is worth asking about. Robinson’s ‘Housekeeping’ was very well-reviewed in 1981,but there wasn’t craziness like what.

Furthermore, I think there is a question of whether bias played a role in Franzen’s reception. A few years ago, the NYT surveyed editors, critics, and writers on the best works of fiction over the quarter century. There was an underrepresentation of women, but also other groups. There tended to be “big novels” at the top. Someone posted on their blog that they wondered why small in size novels weren’t considered ambitious. A commenter responded by pointing out ethnic and gender bias. His/her quote was something to the effect of “It’s lame that some people consider only long books by white men worthwhile.” Now I wouldn’t accuse the NYT of that, strictly speaking. But it does feel like those kinds of books get special treatment. One of the people polled in the NYT survey pointed it out too.

“We’ve talked about the underrepresentation of the baby boomers on our list, but in fact they made a strong showing compared with female writers — or, going back to Day 1 of this discussion, any of the other groups on Michael’s catalog of the excluded: nonwhite writers, gay writers, experimental writers, post-boomer writers, and on and on.”

Franzen fits only one of those markers. Does the asburd reaction exemplify, in part, biases of the literary establishment? It’s a fair question.

I think Sal Gentille put it best: “Is there an element of sour grapes in Picoult’s and others’ complaints? Perhaps. But it might be unwise to cut the conversation short, as some have suggested. David Ulin of The Los Angeles Times, for one, acknowledged the gender disparity in mainstream literary coverage, only to dismiss the criticism of Franzen as motivated by “gossip, envy, a mean-spirited approach to literary life.”

That may be true, but it distracts from the underlying issue: whether the coverage of Franzen is symptomatic of gender bias in literary criticism, and whether journalists are taking sufficient responsibility for that bias.”

While plenty of women writers get positive reviews, how many enjoyed the accolades and coverage Franzen got? There isn’t one of Alice Munro’s collections that lead to a Time magazine cover AND the term ‘masterpiece’ in the first sentence of a review.

LikeLike

Thanks for your detailed, thoughtful comment, DarkLayers.

I agree with you that the Franzen coverage is hyperbolic, breathless, and generally overblown–especially as I’m finishing up Freedom right now and not particularly enjoying it.

As I tried to indicate in my post, I see the issue less as a matter of gender representation and more as a kind of commentary on what is and is not literature (especially canonical literature).

While I’m no proponent of Harold Bloom’s theories, I think his writings about “The School of Resentment” are instructive (if highly imperfect) here.

I think the canon bears out over time: dust has to settle into sediment, and then the worthy works metaphorically float up. I think there are great examples of this in both Herman Melville and Zora Neale Hurston. In turn, there’s nothing to say that 100 years from now that Franzen will be *the* zeitgeist writer for the early 21st century.

As for the Time magazine thing: sure, Alice Munro wasn’t on the cover–but I think the last writer on the cover was Stephen King, and that was a decade ago.

Lydia Davis hasn’t been on the cover, nor Margaret Atwood, nor Renata Adler…nor plenty of male writers for that matter.

Simply put, literary writers aren’t valued in our society like they used to be, and I think it’s great that an organ of the dominant culture signaled that ordinary folks needed to take note of a living, breathing writer. In turn, I think it’s rotten that Picoult and Weiner used the moment to denigrate literature. To me, their comments are as bad as those of “critics” like BR Myers and David Shields who are, I believe, essentially anti-literature.

There is probably, almost certainly, a bias for white males in the literary establishment. This is a bias that is echoed in almost every other aspect of American culture and society, and therefore, somewhat unsurprising. I’m not saying that we should ignore the bias, and I think that there have been tremendous gains in the past 50 years in both recognizing and undoing it–but petty backbiting is not the right way to call attention to this bias.

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughtful reply…I guess we’ll probably wind up agreeing to disagree. The thing about gender and the “literature versus pop art” debate is that the bar does seem to vary from male to female authors. I thought the most relevant point was the commercial male authors with double reviews from that blog post. Some other stuff seems relevant here. So I’ll just link to it, as there are a couple of valuable points.

http://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2010/09/data-2

I guess you would contend that it was this just wasn’t the place to interject those concerns, which is fair enough. I was just really struck by the NYT results a few years ago and the rapture for Franzen seems to collectively value a specific kind of work.

Anyway, I think we can leave it at agreeing (a) that bias is unfortunate, (b) the literary establishment went overboard in their coverage of this book, (c) Piccoult and Weiner aren’t writing stuff for the ages, and (d) the scholars, readers, and writers of tomorrow get to settle these questions and decide merit. (Wouldn’t it be nice if showed some consideration for them before making raves of that sort?)

Much as I’m ambivalent about the book, I hope it becomes more enjoyable for you!

LikeLike

For what it’s worth, I think that the NYT is *way* overvalued as an organ of literary criticism; I’ve gone after Kakutani a couple of times on this site.

I actually just read another huge chunk of Freedom tonight (like, almost 100 pages) and just increasingly hate it, which probably has to do with it being so wildly overrated. It’s amazingly easy to read because you never have to think; it’s like Franzen is doing all the thinking. It’s almost like a lecture.

LikeLike