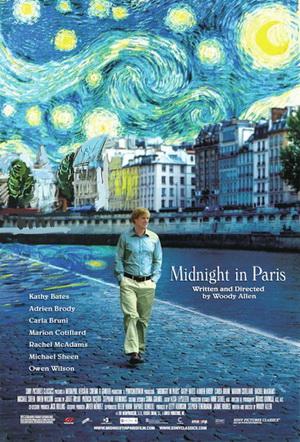

Woody Allen’s new film Midnight in Paris opens with a sumptuous montage of the City of Light, clearly establishing from the get-go that the movie is Allen’s love letter to Paris. The romantic overture idealizes Paris, just as the film’s protagonist Gil, played pitch perfect by Owen Wilson, idealizes the Lost Generation of writers and artists who populated the cafes and bars of Paris in the ’20s. Gil is on a working vacation with his fiancé and future in-laws; he’s a successful Hollywood screenwriter but dreams of becoming a great novelist. Only he’s struggling with his novel-in-progress, which features a protagonist who runs a nostalgia shop. Nostalgia, or the romance of nostalgia, is the primary idiom of Midnight in Paris, and Owen Wilson transcends the usual parameters of Woody-surrogate in bringing this idiom to life. Wilson’s breezy charisma propels the movie forward at all times; indeed, the entire plot rests on Wilson’s charm, which saves the film from falling into syrupy dreck or boring indie whimsy.

Midnight in Paris works to literally charm its viewers and its protagonist, transporting the narrative back into the ’20s via a magical motorcar, where Wilson’s Gil falls in with a host of notable writers, artists, dancers, and other personalities. There are Cole Porter and Salvador Dali, Man Ray and Luis Bunuel, Pablo Picasso and Josephine Baker—but the standouts are the Fitzgeralds, Gertrude Stein, and Ernest Hemingway. The Hemingway character is a marvelous parody of both Hemingway’s caricature and Hemingway’s prose—although I think the humor in his scenes was lost on more than a few of the audience members I watched the film with. On Hemingway’s advice, Gil submits his manuscript to Gertrude Stein for an honest critique. In the meantime, Gil engages in a romance with Adrianna, Picasso’s muse and mistress, who herself pines for the Belle Époque era. Through another magical transposition, Gil and Adrianna move again through time, heading back to the 1890s to meet Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Gaugin. As Gil pursues a romance with Adrianna (and the nostalgia of an idealized past), his own fiancé seems to be spending a bit too much time with a windbaggish and pretentious American who is a visiting lecturer at the Sorbonne. The reality of this conflict pulls Gil into making dramatic choices about his own future.

Midnight in Paris falls squarely into Allen’s fantasy films like The Purple Rose of Cairo, A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, Alice, and Shadows and Fog. The film has much to offer those who, like Gil, find themselves fascinated by the romance of the Lost Generation. Allen’s parodies of the Fitzgeralds, Hemingway, and the rest are loving and gentle, and will surely be appreciated by most English majors. At the same time, Midnight in Paris is a slight, ephemeral work, one that relies on beautiful cinematography and the charm of its lead character more than plot, insight, or even jokes. There is no risk or danger in Gil’s fantasy, no sense that his sanity is in jeopardy or that he might not come to realize the theme of the film, which he spells out clearly for the audience if they somehow missed it—the tendency to romanticize the past has more to do with a dissatisfaction with the present than with any objective evidence that the past was somehow better, and dissatisfaction with the present should be viewed positively, for dissatisfaction can be productive and meaningful if we engage it. Recommended.

[…] Midnight in Paris – Woody Allen (biblioklept.org) […]

LikeLike

[…] Midnight in Paris – Woody Allen (biblioklept.org) […]

LikeLike

Nice post on a charming flick. Corey Stoll as Hemingway is tops.

LikeLike

[…] out Biblioklept for another take. Affiliate […]

LikeLike