We often identify genre simply by its conventions and tropes, and, when October rolls round and we want scary stories, we look for vampires and haunted houses and psycho killers and such. And while there’s plenty of great stuff that adheres to the standard conventions of horror (Lovecraft and Poe come immediately to mind) let’s not overlook novels that offer horror just as keen as any genre exercise. Hence: Seven horror stories masquerading in other genres (and see our first post for more):

Oedipus Rex — Sophocles

Sure, Aristotle tells us that tragedy, by its very nature, must involve pity and terror, two emotions fundamental to horror as well. But the Oedipus story is so fundamental to our culture and its narratives that we easily overlook the plain fact that it is a horror story. Oedipus Rex begins with the attempted infanticide of the hero, including the brutal pinning of his feet, from which his name derives. Spared, Oedipus must endure the horrific uncertainty that he is not his parents’ natural son, a problem compounded when he learns from the Delphic oracle that he is predestined to kill his father and mate with his mother. You know what unfolds: a murder on the high road, a monster with riddles, a curse of famine, a horrible revelation, a suicide, and a bloody blinding.

Julius Caesar — William Shakespeare

History is its own horror show; Julius Caesar might be about the Roman Empire or the price of a republic, but it’s also very much a tale of paranoia, murder, and ghosts. Poor wavering Brutus recapitulates the crime of Oedipus when he stabs father-figure Brutus. The conspirators bathe their hands in Caesar’s blood, hoping to signal rebirth and shared responsibility, but the marking gestures are ultimately ambiguous. Great Caesar’s ghost will return, suicides will abound (Portia swallowing hot coals is particularly gruesome), and war will ravage the Republic.

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find” — Flannery O’Connor

This one may be a bit of a cheat, because I’m sure plenty of folks have the good sense to see “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” as the horror story it is. Still, O’Connor’s short masterpiece too often gets pushed into the “Southern Gothic” or even “Southern Grotesque” mini-genre, one which belies the story’s intense powers of horror. The intensity of “A Good Man” comes largely from its crystalline reality; half a century after its publication, the Misfit still has the power to shock readers (notice too that the Misfit’s first crime was again Oedipal—he was jailed for patricide). Here’s O’Connor on her story:

Our age not only does not have a very sharp eye for the almost imperceptible intrusions of grace, it no longer has much feeling for the nature of the violence which precede and follow them. The devil’s greatest wile, Baudelaire has said, is to convince us that he does not exist.

I suppose the reasons for the use of so much violence in modern fiction will differ with each writer who uses it, but in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work. This idea, that reality is something to which we must be returned at considered cost, is one which is seldom understood by the casual reader . . .

The Kindly Ones — Jonathan Littell

Keeping our Oedipal theme alive is Littell’s enormous novel The Kindly Ones, a horror story masquerading as a historical epic. The Kindly Ones, taking its name from the Greek tragedy, is about an SS officer who carries out probably every taboo one can think of during WWII, including incest, patricide, fantasies of coprophilia and cannibalism, and child murder. Oh, and mass murder. Lots and lots of mass murder. In my review, I argued that, “This is a novel that might as well take place in the asshole,” and I stick by that.

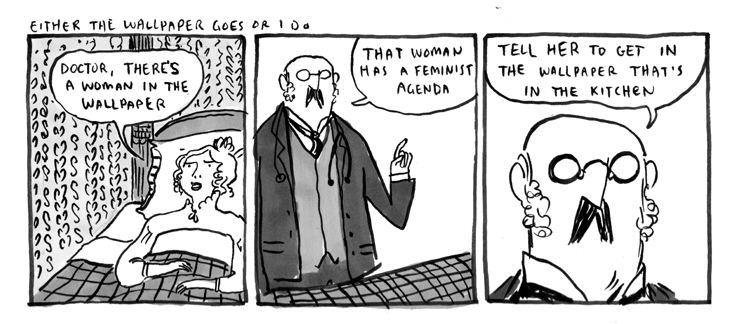

“The Yellow Wallpaper” — Charlotte Perkins Gilman

“The Yellow Wallpaper” has become a central text in feminist criticism for good reason. The story, told in first person POV, is a sad, scary descent into madness. And while it’s easy to point toward postpartum depression as the culprit, the story deserves a much more considered analysis, one which addresses the literal and metaphorical constraints placed upon the female body—a body that literary traditions have often tried to keep lying down (consider Sleeping Beauty, for example).

Steps — Jerzy Kosinski

Steps is an odd duck even for this list, because I’m not even sure if it’s ever been identified within a genre by any large group of readers. From my review:

At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Consider the vignette at the top of the review, which begins with an autophagous octopus and ends with a transvestite. In the world of Steps, these are not wacky or even grotesque details, trotted out for ironic bemusement; no, they’re grim bits of sadness and horror. At the outset of another vignette, a man is pinned down while his girlfriend is gang-raped. In time he begins to resent her, and then to treat her as an object–literally–forcing other objects upon her. The vignette ends at a drunken party with the girlfriend carried away by a half dozen party guests who will likely ravage her. The narrator simply leaves. Another scene illuminates the mind of an architect who designed concentration camps. “Rats have to be removed,” one speaker says to another. “Rats aren’t murdered–we get rid of them; or, to use a better word, they are eliminated; this act of elimination is empty of all meaning. There’s no ritual in it, no symbolism. That’s why in the concentration camps my friend designed, the victim never remained individuals; they became as identical as rats. They existed only to be killed.” In another vignette, a man discovers a woman locked in a metal cage inside a barn. He alerts the authorities, but only after a sinister thought — “It occurred to me that we were alone in the barn and that she was totally defenseless. . . . I thought there was something very tempting in this situation, where one could become completely oneself with another human being.” But the woman in the cage is insane; she can’t acknowledge the absolute identification that the narrator desires. These scenes of violence, control, power, and alienation repeat throughout Steps, all underpinned by the narrator’s extreme wish to connect and communicate with another. Even when he’s asphyxiating butterflies or throwing bottles at an old man, he wishes for some attainment of beauty, some conjunction of human understanding–even if its coded in fear and pain.

“The Shawl” — Cynthia Ozick

Ozick’s short story “The Shawl” is a study in desperation and fear, and while any hack can milk horror from a concentration camp setting and a sick child, Ozick’s psychological study of a mother and her children skewers any hope of a simple sympathetic reading. At its core, “The Shawl” is about the dramatic Darwinism that underpins our fragile bodies, a Darwinism that can, under the right circumstances, remove our humanity. I never want to read “The Shawl” again.

Freudian typo:

“he is predestined to kill his father and mate with his father.”

LikeLike

ugh. jeez. thx for the spot — emended.

LikeLike

Ok, since you asked (what do you mean you didn’t?) a terrifying thirteen:

1 Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, The Jew’s Bech-Tree (1842) Unsettling short-novel in the tradition of the German uncanny

2 Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Spinning Gears (Cogwheels) (1927) Death-haunted visions

3 Leo Perutz, The Master of the Day of Judgement (1930) Metaphysical Horror-Thriller

4 Sadegh Hedayat, The Blind Owl (1937) Depressive, claustrophobical masterpiece of Persian literature

5 Fredric Brown, Here Comes a Candle (1950) Weird, experimental horror published as crime

6 Juan Rulfo, Pedro Páramo (1955) A ghost story

7 Roland Topor, The Tenant (1964) Classic about identity and the pressure to conform which became a horror movie

8 Flann O’ Brien, The Third Policeman (1967) Yes, I find it horrifying

9 Michael Moorcock, The Black Corridor (1969) Most scary SF novel of all-time

10 Muriel Spark, The Driver’s Seat (1970) Kind like Patricia Highsmith or Shirley Jackson, but with less optimism and faith in humanity

11 Ingeborg Bachmann, The Barking (1972) One could make claims for both her major novels, but this short story is even structurally horror

12 Derek Raymond, I Was Dora Suarez (1990) Well, just look at a synopsis

13 Jack O’ Connell, World Made Flesh (1999) Starts with a flaying and gets better (worse?)

LikeLike

[…] Seven more horror stories masquerading in other genres […]

LikeLike