Adam Novy’s novel The Avian Gospels synthesizes dystopian themes with magical realism to tell the story of an unnamed city, in an unnamed time, afflicted by plagues of birds and bands of Gypsies. The novel is marvelous, surreal and very strange, disorienting in its tones and unnerving in its subjects; it’s at once a confounding allegory of torture, suppression, and rebellion, and at the same time a study in intrafamily relationships.

There are two families at the heart of The Avian Gospels. The aristocratic Giggs are led by the Judge, a ruthless patriarch who is both inheritor and perpetrator of endless war. Judge Giggs controls the city through fear, torture, and his fascist personal guard, the RedBlacks. While Judge Giggs seems to hold illimitable power in the city, it isn’t enough to retain the love or even respect of his family. His wife veers into a manic depressive breakdown, brought on in large part by the death of her elder son, who was killed during the last (foolish) war. His second son, Mike, is a loutish ne’er-do-well, a bully who fails to win his father’s approval. The Judge’s daughter Katherine is the apple of his eye, but as she matures in her adolescence, she begins to perceive the violent disconnect between her privileged life and the suppression and poverty forced on the city’s Gypsy population.

The other family (perhaps more of a duo, really) comprises Zvominir, an immigrant claiming to hail from Sweden, and his son Morgan, a petulant teen of an age with Katherine. Routinely beaten bloody by Mike Giggs and his RedBlack goons, Morgan develops a visceral hatred of the Judge’s regime, one that leads the lad to repeatedly (and rashly) lash out against the violent injustice he perceives around him. Zvominir and Morgan live in sad, motherless squalor, separated not only from the suburban greenzoned upper-class, but also from the Gypsies; Zvominir, who leads most of his life genuflecting to or cowering from power, will not even allow his son the joy of partaking in the Gypsies vibrant customs (like rowdy ska music and barbecues).

Most of all, Zvominir tries to contain his son’s bizarre power, a power that he shares with the boy: they can telepathically control the birds. This gift becomes both blessing and curse as the city is overrun by flocks of birds that block out the sun and make roads unnavigable. Zvominir, always kowtowing to power, agrees to employ his gift to “sweep” the city (particularly the area where the rich folks live) of the bird hordes; Morgan agrees to help, but only under the condition that he be allowed to show off his talent in the public square, where eager crowds (of Gypsies and suburbanites alike) gather to marvel at the spectacle of his “birdshows.” In time, Morgan begins writing dissent into his performances:

Birdshows were generally narrative, and featured a bird-made Morgan being chased through the streets by a soldier who was torn to bits by swans, though the swans were made of pigeons, and the soldier of flesh-colored plovers, his uniform of cardinals and crows. Swans would also be pursued through ghetto canyons by flying tigers made of orioles. These were his intentions for the birdshows, at any rate, but Zvominir would censor when the images betrayed but a hint of dangerous content, obscuring Morgan’s work with birdclouds, or worse, laughing babies made of birds. The audience found these touches psychedelic, and weren’t pacified so much as confused, so their passion turned to mumbles. The elder’s power over birds was superior, and Morgan couldn’t stop his father from suppressing the transgressive. It infuriated him.

Zvominir isn’t the only authority figure prone to parental censorship; as the poor old man tries to keep his son safe by “suppressing the transgressive,” the Judge in turn does all in his power to keep his precious daughter Katherine blind and ignorant to the violence and inequality that has purchased her material comfort. However, Katherine meets and becomes fascinated by Morgan, just as the young man’s rebellious attitude comes to find definition and ideology thanks to the Gypsy rebel Jane. Jane harnesses Morgan’s raw anger, turning him into the figurehead of a Gypsy resistance against the Judge’s terrible regime. She literally ushers him into the Gypsy underworld, a surreal setting of nightplants and black markets and ecstatic ska music and donkeys, sprawling in a labyrinthine network of caves and caverns and tunnels under the unnamed city. From this subterranean site, Jane becomes mastermind of a terrorist plot to overthrow the fascist Judge:

They—we—were helpless, and we knew it. She would do to us what Hungary had done, but with stealth; this terror stuff is easy, she mused. Who needs armies? She was poor, and lived in sewers, so nothing could be taken but her life, while we had homes, jobs, children, hopes, dreams and possessions we adored, which all gave meaning to our lives. There was no end to that of which she could deprive us. Our privilege made us vulnerable.

Now seems as reasonable a time as any to remark upon the narrator of The Avian Gospels, as its pronouns color much of the passage I just cited. A first-person plural “we” tells the story, a “we” whose contours and guts alike become more evident as the book unfolds. Much of the joy (and bewilderment and occasional frustration) I felt reading The Avian Gospels came from puzzling out just who this “we” is. As the book progresses, it becomes clear that, like the collective first plural person who narrates, say, William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” the narrator is part and parcel of the story—is the story, perhaps—and that Novy’s dystopian vision is realized not just in the book’s content, but also in the telling of that content. Calling the narrator unreliable is beside the point; the narrator is the ideology itself that Novy critiques. Rebel Jane provides a very real ideological anesthesia to the narrator’s methods, the Judge’s power, and Morgan’s artistic ambitions:

. . . Jane felt suspicious of beauty, which trafficked in desire, not in justice, and left you lonelier and sadder. It made you feel worse in the guise of feeling better, and left you hungry for more beauty. Further. It enfeebled you politically, by pointing at some hypothetical catharsis, a transcendence that could not be achieved, for who could really say they had communed with a non-religious paradise of aesthetics? The beauty effect: a crescendo of nothing. Beauty distracted from things that were important—the rights of disadvantaged people—in the name of something it claimed was more important, and which didn’t actually exist. It was a cognitive conspiracy, a con that disempowered.

If Jane seems a bit shrewish—and what zealot isn’t?—it’s worth pointing out that her ideas might be the novel’s thesis, a thesis ironically couched in the very beauty that Jane would make us wary of. She’s the cold conscience in a book filled with passions. And she’s a terrorist.

While The Avian Gospels surpasses any allegorical schema we might try to impose upon it, it’s still very much a response to America’s post-9/11 zeitgeist. Novy’s Judge is a figure of malevolence glossed in benevolence. If he’s a sicko who takes dull delight in torturing Gypsies in his Boom Boom Room, he’s also a family man with problems that most of us can relate to. He’s an authoritarian who maintains order in a fractured society through violence and suppression—but he delivers what the suburban greenzoners want from a leader. So what if security comes at the expense of justice, and on the backs of a displaced population to boot?

The Gypsies, refugees from countless wars afflicting the world of The Avian Gospels, aren’t the only displaced persons in the narrative. Novy displaces the readers as well. The Avian Gospels erupts with uncanny moments where the material of our recognizable world overlaps with the crumbled reality of the narrative. Social structures, attitudes, cultural norms and ideals—these remain, more or less. But how to puzzle out a world where China, Bolivia, Angloa, and Oklahoma are among the nations that surround the unnamed city? Or where technology has regressed to the point that the automobile is a thing of the past? (Guns remain). And, uh, the birds, of course.

Novy’s dystopian novel skews more fantasy (or, more properly, magical realism) than sci-fi, but it’s the novel’s strange, shifting tones that most likely will paradoxically estrange and engage most readers. There’s a violent zaniness to The Avian Gospels, but the zaniness is never tinted with even a hint of whimsy. The first-person plural “we” that narrates the text juxtaposes dense, poetic images against the teenspeak of the street. At times, the narrator staggers into a mordant lament, only to retreat into cruel, blackly ironic prose. The effect is disorienting and compelling. Novy’s writing moves rhythmically with a complex energy that I’m faltering to describe. You should probably just read the book.

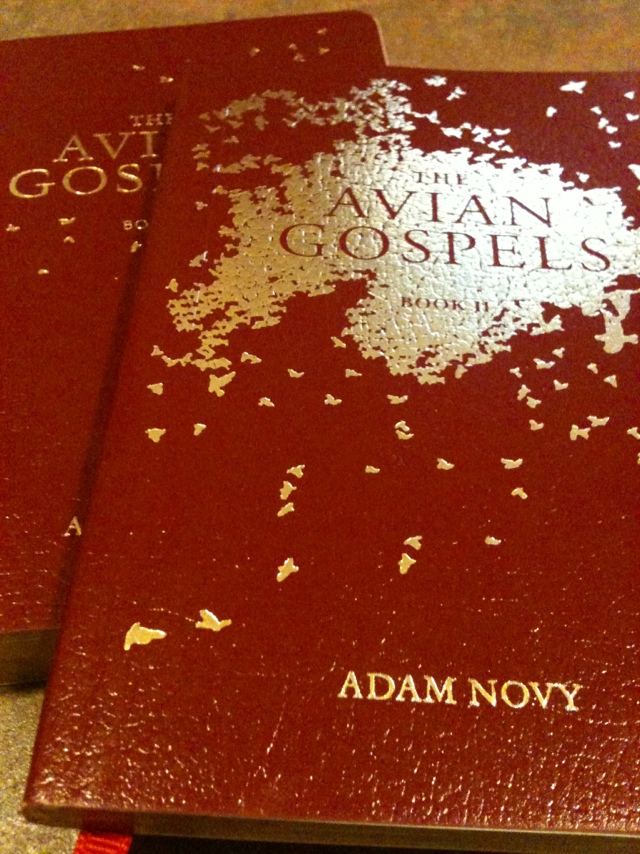

I’ve neglected thus far to comment on the actual physical books that comprise The Avian Gospels. They are beautiful, compact, oxblood volumes with gilded edges and bookmarks, reminiscent of Gideon bibles, I suppose, but more lovely. They’re also very small, the sort of thing that fits easily into a pocket or a purse. I love books like that.

The Avian Gospels deserves a place on the shelf (or in the pocket) of any fan of cult or dystopian novels. It’s a story about cyclical violence, power and powerlessness, and political and cultural repression. It’s also a story about family and parent-child relationships and what it means to love another person in the face of radical danger, a novel that foregrounds the very real stakes of rebellion, both Oedipal and political. It’s a strange book, one that offers little comfort to its readers and certainly proffers no simple answers. Deeply moving and highly original, I strongly recommend this book.

The Avian Gospels is available now from Hobart. Read my interview with Adam Novy.

This book sounds wonderful, and the cover is absolutely gorgeous! Sold! It’s now added to my lengthy to-buy list. Great review!

LikeLike

Great review. Gonna have to add it to our list.

LikeLike

sounds excellent. thanks for posting the review

LikeLike

Excellent review. Sounds extremely interesting, will keep an eye out for this book.

LikeLike

in fact, i just ordered it.

LikeLike

[…] Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. (Read my review). […]

LikeLike

[…] the narrator unreliable is beside the point; the narrator is the ideology itself that Novy critiques.” March 19, 2012 | admin | No Comments […]

LikeLike

[…] you read Adam Novy’s novel The Avian Gospels? It’s good […]

LikeLike

[…] an excerpt of Adam Novy’s work in progress, The Gore and Splatter. I was a big fan of Adam’s last novel, The Avian Gospels, a dystopian take on terror and gypsies and birds. When I interviewed Adam a few years ago, he told me he was “writing a novel about the life […]

LikeLike

[…] Άνταμ Νόβι, The Avian Gospels […]

LikeLike

[…] I just picked up Ursula K. Le Guin’s first novel Rocannon’s World on novelist Adam Novy’s recommendation. (Have you read Novy’s novel The Avian Gospels? It’s great). […]

LikeLike

[…] Novy’s novel The Avian Gospels is fantastic. Buy it from […]

LikeLike

[…] who’s written a number of excellent reviews for Biblioklept, and Adam Novy, whose novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best contemporary novels of the last decade. The weirdest part about hanging out was […]

LikeLike