1. Let me point those of you who may care to my first riff on William Gaddis’s J R, which I wrote about half way into the book, and which will likely provide more context than I’m prepared to offer here. Also, there might be spoilers ahead.

2. The end of J R is heartbreaking. We find some of our principal characters—Bast, Gibbs, and JR—in nebulous spaces, their plans and dreams and hopes crumbling or smoking or fizzing out or jettisoned (pick your verb as I’m too lazy or unequipped).

3. The final face-to-face scene between Bast and JR, the one that begins with them riding in a limousine and ends with Bast’s psycho breakdown—heartbreaking. Little JR, we realize, is most motivated by his intense need for human connection, his desire for family, perhaps, or place, at least. Bast’s rejection of JR—really a rejection of contemporary consumer culture—is almost horrific, even more so because the reader (this reader, anyway) so readily identifies with Bast and JR simultaneously.

4. Here’s Gaddis on his character JR (from The Paris Review interview):

The boy himself is a total invention, completely sui generis. The reason he is eleven is because he is in this prepubescent age where he is amoral, with a clear conscience, dealing with people who are immoral, unscrupulous; they realize what scruples are, but push them aside, whereas his good cheer and greed he considers perfectly normal. He thinks this is what you’re supposed to do; he is not going to wait around; he is in a hurry, as you should be in America—get on with it, get going. He is very scrupulous about obeying the letter of the law and then (never making the distinction) evading the spirit of the law at every possible turn. He is in these ways an innocent and is well-meaning, a sincere hypocrite. With Bast, he does think he’s helping him out.

5. And again:

INTERVIEWER

Which is the novel you care most for?

GADDIS

I think that I care most for JR because I’m awfully fond of the boy himself.

6. In that same interview, Gaddis contends that JR is motivated by “good-natured greed,” which is probably true (see above re: letter vs. spirit). Despite his predatory capitalism, his willingness to strip company employees of basic safety nets, JR remains sympathetic.

7. Why is JR a sympathetic character? He’s just a child, one who lives in a world without adult supervision let alone love and care. In a touching scene that telegraphs the bizarre black humor that runs through the novel, JR suggests that the Eskimos on display at a museum are the work of a taxidermist: That is, said Eskimos were once, like, alive, and are now on display. Amy Joubert, his social studies teacher (and the object of Gibbs’s and possibly Bast’s affection) is moved to both pity and terror by JR’s confusion, and clutches him to her breast.

8. While we’re on Eskimos, which is to say Native Americans, which is to say, perhaps, Indians: The Indian plot in JR fascinates; it recapitulates a bloody, awful past, pointing to the brutal way the quote unquote invisible hand of the market might sweep entire people away and then come back (in a cheap costume) to offer modernity at a price.

9. Ethnic minorities in general find themselves displaced in JR, or at least displaced in the language of JR (and is there a novel that is more language than JR, if such a statement might be permitted to exist (at least metaphorically)? No, I don’t think there is, or at least I don’t know of one). The casual racism of 1%ers like Zona Selk and Cates is ugly and bitter, but the PR man Davidoff is somehow worse—he sees race as something to use, to manipulate, to control.

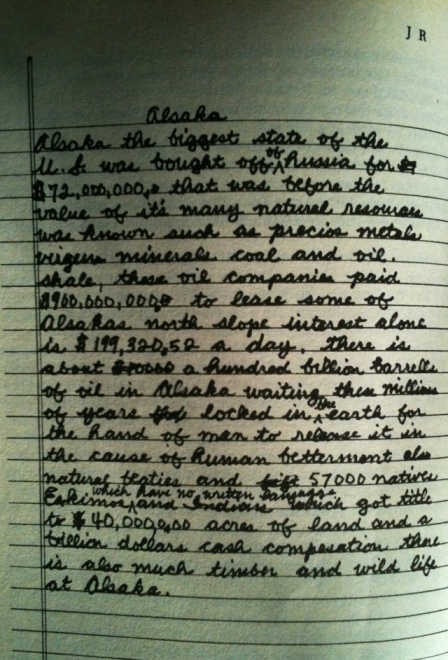

10. And, of course, JR’s infamous “Alsaka Report,” a connection to Manifest Destiny, to the valuation of our ecosystem in the most base and short-sighted terms (there’s a perhaps overlooked streak of environmentalism to JR):

11. Sci-fi elements to JR: The Frigicom process, which promises to freeze noise. The Teletravel transmission process.

12. At the end of JR, we learn that poor diCephalis is lost in Teletravel transmission.

13. I couldn’t help but be reminded—repeatedly—of David Foster Wallace’s work during JR (diCephalis stuck in Teletravel recalls poor Orin in the giant glassjar at the end of Infinite Jest). In general, the loose threads of JR recall Wallace’s loose threads (other way round, I know).

14. The phone motif alone might have led me to compare Wallace to Gaddis—but there’s also all that, y’know, thematic unity.

15. And clearly, too, style. I’m sure that longtime readers of Gaddis have likely made the comparisons already, but throughout his work, Wallace repeatedly uses chapters or sections that comprise only dialogue. A good example is §19 of The Pale King (which I riffed on a bit this summer), a conversation between three IRS agents stuck in an elevator. In some ways, the scene, set only a few years after the publication of JR feels like a strange little sequel, or an echo of a shadow of a chapter of a sequel (or maybe not—just riffing here). Wallace’s concerns about civics, ethics, and compassion seem more straightforward than Gaddis’s angry vision of a desacralized world, a world where symphonies must be chopped into three minute segments to allow for commercial interruptions (or, rather, that symphonies must interrupt commercials). Wallace is obviously writing after the victory of Pop Art, of populism, of the slow sprawling stripmalling of America . . . but I’ve riffed off track (there is no track).

16. ” . . . I mean they never lose these banks don’t, I mean where we’re getting screwed . . . ” — JR laments on page 653 of my Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition.

17. The above quote as the briefest illustration that, published in 1975, JR is more relevant than ever.

18. To wit, Gaddis again, again from The Paris Review interview, commenting on hollow, false values:

. . . I’d always been intrigued by the charade of the so-called free market, so-called free enterprise system, the stock market conceived of as what was called a “people’s capitalism” where you “owned a part of the company” and so forth. All of which is true; you own shares in a company, so you literally do own part of the assets. But if you own a hundred shares out of six or sixty or six hundred million, you’re not going to influence things very much. Also, the fact that people buy securities—the very word in this context is comic—not because they are excited by the product—often you don’t know what the company makes—but simply for profit: The stock looks good and you buy it. The moment it looks bad you sell it. What had actually happened in the company is not your concern.

19. Gaddis’s take on the “art” of capitalism: design mock ups for a potential logo for the JR Family of Companies:

20. JR is one of the most prescient novels I’ve ever read—and not just in its illustration of the the chaos at the intersection of corporatism, Wall Street, government, and military, but also in its handling and treatment of education. Gaddis is way ahead of an ugly curve, showing us an educational system largely disinterested in intellectual, aesthetic, or even athletic development. Instead we get a storehouse for children, reliant on programmed lessons delivered via technology and assessment by standardized testing. It’s ugly and it’s more real than ever now.

21. And here’s Gibb’s railing against it, in a way, in (what’s likely a half-drunken or at least hung-over) rant to his students:

Before we go any further here, has it ever occurred to any of you that all this is simply one grand misunderstanding? Since you’re not here to learn anything, but to be taught so you can pass these tests, knowledge has to be organized so it can be taught, and it has to be reduced to information so it can be organized do you follow that? In other words this leads you to assume that organization is an inherent property of the knowledge itself, and that disorder and chaos are simply irrelevant forces that threaten it from the outside. In fact it’s the opposite. Order is simply a thin, perilous condition we try to impose on the basic reality of chaos . . .

(That’s from page 20 of my Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition, by the bye).

22. There are no happy families in JR. Just broken families.

23. I said this at the top of the riff, but again–-heartbreaking.

24. This is probably a direction out of this riff—to resuscitate the emotional dimension of the novel, which is too easily overlooked, perhaps, because Gaddis’s manipulations (and all novelists manipulate their audience) require so much active participation from the reader. JR is without exposition, without the overt imposition of the novelist telling us how to feel: instead there’s a thickness to it, a building of buzz and clatter, yes, but music under all that noise: even a kernel of love (and hope!) under the heavy folds of anger.

25. Very highly recommended.

“JR is one of the most prescient novels I’ve ever read—and not just in its illustration of the the chaos at the intersection of corporatism, Wall Street, government, and military, but also in its handling and treatment of education. Gaddis is way ahead of an ugly curve, showing us an educational system largely disinterested in intellectual, aesthetic, or even athletic development. Instead we get a storehouse for children, reliant on programmed lessons delivered via technology and assessment by standardized testing. It’s ugly and it’s more real than ever now.”

Hear hear. The man was a soothsayer. JR is the book that opened up postmodernism for me in that I finally was reading literature that was both of its time but forward-looking, predictive, etc… in ways that the realists/minimalists that were in vogue while I was in my formative years of study were not and never could be. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.) Even today’s big names of lit-fic, Franzen, Eugenides, Patchett write books that trail in the wake of the world. Gaddis was looking at the horizon. The influence on DFW can’t be understated.

Gaddis is way under appreciated, sometimes just an afterthought behind DeLillo, Pynchon, etc…but he’s a giant.

LikeLike

Love your phrase: “Even today’s big names of lit-fic, Franzen, Eugenides, Patchett write books that trail in the wake of the world. Gaddis was looking at the horizon.”

I think the problem for many young readers (here young = undergradish, early 20s) is that they’re just underequipped for Gaddis, and there isn’t the same academic system in place to rigorously equip them (in contrast with, say, Faulkner or Joyce). So Gaddis’s books are daunting because they are so big and so chock full of allusion, and for inexperienced readers, they are a challenge especially because such readers are undertrained, or, more to the point, not able to learn how to read these books on the book’s own terms (I might compare it to viewers who find Malick’s films incomprehensible because they attempt to impose their own narrative logic on the film).

I think that Wallace “taught” me how to read Gaddis.

LikeLike

I think you’re right about the lack of academic system to help introduce students to postmodern works, particularly the “difficult” ones like JR. In a lot of undergraduate English majors it’s as though literature ended with modernism, and/or postmodernism is taught as theory, as opposed to tackling the literature of the age. There was a generation of academics that codified (or maybe decoded) Faulkner, Eliot, Joyce, etc for students…, but the next generation ate its own tail.

I’m sort of hopeful that the impact of DFW as a progeny of Gaddis et al…may re-open the discourse a bit and bring us back to books like JR.

LikeLike

I agree with you—when I was an undergrad, I was exposed to postmodernist writers (Barth, Coover, Bartheleme, etc.) waaaaaaay too soon—I’d read so little of what came before. Then, there was all the Foucault and Derrida and that stuff, which ultimately obscures the literature or art, or even worse is used to replace it.

For me, Wallace is a central figure because he gets past the empty gamesmanship I find in Barth (to pull out one example). JR seems prototypical of what Wallace is doing.

LikeLike

I’m really glad you dug this one. It’s one of my favorites. People always compare Wallace to Pynchon, but I’ve always thought he owed a lot more to Gaddis. Thinking I need to reread this one soon.

LikeLike

Your enthusiasm for JR is appreciated and echoed here; thanks for renewing my desire to open it yet again. For me it’s the monolith in 2001: a thing literally MADE of words, each conjoined like masonry of pure sound. And yes, there is a heart there, beating, always.

LikeLike

Oh man I’m so glad you liked it! I agree with Daryl that yr thoughts are making me want to pick it up again, soon. nice job bringing Malick into it at the end there. I would love to know how much overlap there is between Gaddis fans and Malick fans. Or if it’s even possible to LOVE JR and HATE Tree of LIfe, or vice versa.

LikeLike

I’m interviewing Stuart Kendall about his new translation of Gilgamesh right now; he’s written a book about Malick. So I’m bending over backwards trying to figure out how to ask a question to connect the two in a way that’s not amateurish or awkward.

LikeLike

Maybe I’ll have to give it a try. I was stymied by The Recognitions about 1/3 of the way into it, but perhaps JR is a better starting place.

LikeLike

I crapped out on The Recognitions after getting half way into it, but I found JR immediately engaging—much funnier, and, though more difficult, more assured. It’s also somehow less showy.

LikeLike

Good post, Blblioklept. _J R_ is a heck of a book. Somewhere, maybe on the Gaddis site, there’s a late piece: the grown-up J R as a bureaucrat.

“Sci-fi elements to JR: The Frigicom process, which promises to freeze noise. The Teletravel transmission process.” One thinks of Vonnegut’s _Cat’s Cradle_ (ice-nine) and Heller’s Lepage glue gun from _Catch-22_.

Most times people stumble across this book (and others by Gaddis), when they’re not thrust at them, but when Wallace was first popular he acknowledged the influence of Gaddis and, I hope, turned people on to him. If you read _A Frolic of His Own_ I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts on it.

Thanks again for the post.

Jeff Bursey

author of

_Verbatim: A Novel_

LikeLike

Cheers, Jeff. I’m giving Recognitions another shot (I stalled out at half way through last time), and then I’ll see about Frolic or CG.

Cat’s Cradle is my favorite Vonnegut.

LikeLike

[…] humor tips over into a screed of despair. A more mature Gaddis handles bitterness far better in JR, I think—but I parenthesize this note, as it seems minor even in a list of minor […]

LikeLike

[…] Biblioklept reviews J R (part 2) […]

LikeLike

[…] with this review, perhaps more than I struggled with writing about J R (which I did here and here) or The Recognitions (which I did here and here), which seems nonsensical because those books are […]

LikeLike

Number 8 repeats in Carpenter’s Gothic if you understand the history of Long Island. But maybe that’s what I bring to it rather than what Gaddis intended.

I would need a 3d read of JR to feel empathy for JR himself. Mostly he sickened me, even though I know kids need adults to help them comprehend the world. Though I understand Gaddis’s decision to make him pre-pubescent. I always imagined JR to be the product of a family who sees the world in the way JR sees it. I understood the whole book to be Gaddis wrestling with American values, being part of American society yet not part of it. Obviously he cares little for financial chicanery, destructive selfishness, short-sightedness. All those things are a game to an 11 year old. Like taking Monopoly games from Family Game Time at home, and putting them into practice. Fun! At 11 you can’t see long-term impacts, or don’t care about them if you do.

It’s one way Gaddis can say American culture exists at the level of an 11-year-old. I’ve argued recently that America is like a drunk teenager who just found the keys to his parents’ care while they’re away for the weekend. He goes out joyriding and causes all kinds of mayhem, unable to think beyond his own immediate fun. He’s still driving and hasn’t run out of gas, hasn’t had a collision that stops the car from operating.

One of the big points of JR to me is how it foreshadowed the junk bond and arbitrage games of the 80s. It’s like Gaddis knew Boesky, Milken and friends while writing this one.

LikeLike

I have yet to read CG or Frolic.

I get your reaction to lil JR—I mean, his actions are detestable, but he’s also not really morally culpable for them—in fact, he’s playing by the rules. Bast’s reaction to him at the end of the book is really shattering to him, I think. As far as his family, I always interpreted him to have been abandoned by dad and mom was always working—basically an orphan, or at least a latchkey kids.

I agree that JR is predictive—in his ’87 interview at Paris Review, Gaddis comments on how his critique has come to fruition; 25 years after that interview, its attack on Wall St. and corporatism and greed is more meaningful than ever, sadly.

LikeLike

[…] major highlight of the year was finally reading William Gaddis’s novels The Recognitions and J R. I also read Gaddis’s posthumous novella AgapēAgape, an erudite rant that purposefully […]

LikeLike

William Gaddis was my father’s sister’s husband. As a teenager I was priviledged to spend time at his house as he was finishing J.R.. Many of the observations herein are dead on. I recall long summertime conversations on philosophy, art, history, politics and economics, thought the passage of time may have clouded and altered the memories, William Gaddis remains a major force in shaping my current world views. I have definite memories of his writing studio and the amount of time he spend rewriting single phrases.

LikeLike

John, I’d love to read about your memories.

LikeLike

[…] This is seriously big and seriously American. (image) […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on happy souls in hell.

LikeLike

[…] his amazing debut novel The Lost Scrapbook) is William Gaddis’s stuff, particularly J R—the verbal dazzle, the few stray lines of poetic stage-setting in lieu of traditional […]

LikeLike

[…] I’m going through William Gaddis’s novel J R again (via Nick Sullivan’s amazing audiobook […]

LikeLike

[…] From William Gaddis’s novel J R. […]

LikeLike

[…] I offer more description of the novel’s plot and form than I intend to here, maybe), and a thing I wrote after finishing it which (this thing I wrote before, I mean) might be better than anything I can muster here, in terms […]

LikeLike

Am wanting to take the Gaddis plunge, but unsure where to start. At the beginning with The Recognitions or with one of the three I already have…that being: JR, Agape Agape or Carpenter’s Gothic? I am presently leaning toward JR. Suggestions?

LikeLike

JR. Don’t read Agape Agape until you’ve read JR; Agape is kind of a sequel to it.

LikeLike

Well, I ended up at my local bookshop where they had The Recognitions. Couldn’t resist the temptation. So with that, then JR and then Agape Agape my summer reading list should be set.

LikeLike

Agape Agape was a great coda to JR, thanks for the recommendation. I’ve decided to stop at Carpenter’s Gothic and leave A Frolic of His Own for a later date. But God damn after months of Gaddis where does one go? Many signs and auguries seem to be pointing to me to DFW’s The Pale King–your post on phantoms vs. ghosts being such a nudge–but there’s 2666, The Tunnel and others flapping their covers at me…but Wallace, just seems inevitable

LikeLike

Try Evan Dara’s THE LOST SCRAPBOOK

LikeLike

[…] Knopf paperback copy of William Gaddis’s novel J R. The book is one of my favorites—I first read it in 2012 and then again in 2016 (which maybe means I’ll reread it again in 2020?). I’ll cobble […]

LikeLike