The classical Greeks understood that literature is a form of competition. The eminent literary critic Harold Bloom folded a bit of Freudian psychology into this insight, describing the “anxiety of influence” that lurks beneath the impetus to write, the motivation to enter into an agon with the history of letters, to Oedipally assassinate—or at least assimilate—one’s literary forebears. To put this another way: What does it take to write after, say, The Odyssey? How does one answer to The Book of Job? The gall to write after Don Quixote, after Shakespeare, after Dostoevsky, after George Eliot . . .

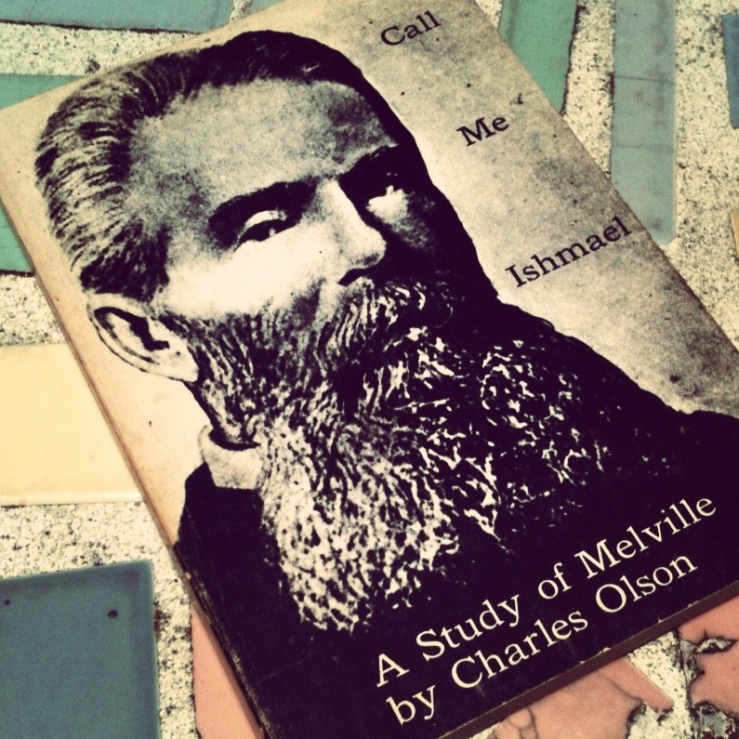

What about Moby-Dick? What are the possibilities of even writing about Moby-Dick? (One thinks here of Ishmael’s own futile attempts to measure whales). How could Melville write after Job? After Lear? After Moby-Dick? How did Melville assimilate the texts that presented the strongest anxieties of influence in his opus? Could Melville survive the wreckage of The Pequod? These are the questions that poet-critic Charles Olson tackles—sometimes directly, sometimes obliquely, and always with brisk, sharp language—in Call Me Ishmael, his study of Melville and Moby-Dick.

Here’s one answer to my list of questions. It comes early in Olson’s book:

The man made a mess of things. He got all balled up in Christ. He made a white marriage. He had one son die of tuberculosis, the other shoot himself. He only rode his own space once—Moby-Dick. He had to go fast, like an American, or he was all torpor. Half horse half alligator.

Melville took an awful licking. He was bound to. He was an original, aboriginal. A beginner. It happens that way to the dreaming men it takes to discover America . . . Melville had a way of reaching back through time until he got history pushed back so far he turned time into space. He was like a migrant backtrailing to Asia, some Inca trying to find a lost home.

We are the last “first” people. We forget that. We act big, misuse our land, ourselves. We lose our own primary.

Melville went back, to discover us, to come forward. He got as far as Moby-Dick.

This passage illustrates Olson’s forceful, often blunt prose, the kind of language that cracks directly at Melville’s own impossible prose in Moby-Dick. I think here of the critic James Wood’s notation in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” that

The writer-critic, or poet-critic, has a competitive proximity to the writers she discusses. The competition is registered verbally. The writer-critic is always showing a little plumage to the writer under discussion. If the writer-critic appears to generalize, it is because literature is what she does, and one is always generalizing about oneself.

Olson may generalize as he shows a little plumage to master Melville, cutting through huge swaths of history and making poetic leaps into strange similes, but Call Me Ishmael is ultimately keenly attenuated to detail, to the processes of Melville’s constructions at the historical, economic, psychological, religious, and, yes, literary level. Although a slim 119 pages in my 1947 City Lights edition, Call Me Ishmael nevertheless vividly conveys the sources Melville synthesized to create Moby-Dick.

The book begins with an unsourced account of the whaleship Essex, attacked and destroyed by a sperm whale in the Pacific in 1820, a year after Melville’s birth. Olson trusts his readers to connect The Essex to The Pequod. Unlike so much literary scholarship, Olson’s Ishmael doesn’t torture every element of the text into overwrought explications. He provides an overview of the importance of whaling-industry-as-world’s-fuel source in a chapter that reads more like a prose poem than a stuffy history book, and then, in a chapter appropriately titled “Usufruct,” offers up entries from Melville’s own journals as primary evidence of the material that led to Moby-Dick. Olson rarely sticks his nose in here, letting the reader synthesize the selections.

Olson then plumbs Moby-Dick’s literary roots, delving into Shakespeare, particularly Lear and Antony and Cleopatra. He attends to Melville’s own annotations to Shakespeare, and then points out Melville’s literary/political condensation:

As the strongest force Shakespeare caused Melville to approach tragedy in terms of the drama. As the strongest social force America caused him to approach tragedy in terms of democracy.

It was not difficult for Melville to reconcile the two. Because of his perception of America: Ahab . . .

Ahab is the FACT, the Crew the IDEA. The Crew is where what America stands for got into Moby-Dick. They’re what we imagine democracy to be. They’re Melville’s addition to tragedy as he took it from Shakespeare. He had to do more with the people than offstage shouts in a Julius Caesar. This was the difference a Declaration of Independence made.

The Shakespeare section of Call Me Ishmael marvels: Olson’s perceptive powers simultaneously enlighten and make seemingly-familiar territory dark, strange. He then moves into a discussion of post-Moby Melville, a man perhaps crushed by his own achievement—not by any financial success, no, definitely no, but the metaphysical success. Like a Moses, Melville had found the god he so desperately needed:

Melville wanted a god. Space was the First, before time, earth, man. Melville sought it: “Polar eternities” behind “Saturn’s gray chaos.” Christ, a Holy Ghost, Jehovah never satisfied him. When he knew peaces it was with a god of Prime. His dream was Daniel’s: the Ancient of Days, garment white as snow, hair like the pure wool. Space was the paradise Melville was exile of.

When he made his whale he made his god. Ishmael once comes to the bones a Sperm whale pitched up on land. They are massive, and his struck with horror at the “antemosaic unsourced existence of the unspeakable terrors of the whale.”

When Moby-Dick is first seen he swims a snow-hill on the sea. To Ishmael he is the white bull Jupiter swimming to Crete with ravished Europa on his horns: a prime, lovely, malignant white.

Olson agrees with an 1856 journal entry by Nathaniel Hawthorne that he cites at length: Melville “can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief.” In Olson’s analysis, after having found god-in-the-whale, Melville plummets into an existential crisis. He gives over to his inner-alligator, torpid, enervated, numb, but still fierce and potent and monstrous. “He denied himself in Christianity,” writes Olson, linking the downward spiral of Melville’s career and family life to this religion.

To this end, Olson is too dismissive of Melville’s later work; when he can find nothing of the “old Melville” to praise in Benito Cereno, Bartleby, or Billy Budd, it’s almost as if he’s willfully ignoring evidence that contradicts his thesis. These are marvelous books, and if they can’t win a contest against Moby-Dick, it’s worth pointing out that little of what’s been written after that book can.

And yet we can write after Melville; we can even write on Melville. The will and vitality of Olson’s forceful, intelligent prose opens a way, or at least exemplifies a way. At the same time, paradoxically, a reading of Call Me Ishmael seems to foreclose the need, if not the possibility, of reading another study of Moby-Dick. This statement is not meant to be a knock against Melville scholarship. Here’s the thing though: life is short, time is limited, and if one plans to read a book about Moby-Dick, it should be Olson’s Call Me Ishmael. It’s great, grand stuff.

✌

LikeLike

There are many who will contend The Confidence-Man is certainly in the same league as Moby-Dick. One’s assessment will be determined, though, by how much trust you have that the parts constitute a whole. (I am inclined to think so.) If this is the case, I would claim that his final novel is his far more subtle masterpiece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece, thanks. Makes me want to read Moby Dick again, and then this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] year, although it’s not “Bartleby” that sparked the desire—chalk it up to Charles Olson’s amazing study Call Me […]

LikeLike

[…] Prompted by Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson’s marvelous study of Moby-Dick, I took a fifth trip through Melville’s massive opus this past […]

LikeLike

If some one desires to be updated with hottest technologies

afterward he must be go to see this site and be up to date everyday.

LikeLike

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your

feed and I hope you write again very soon!

LikeLike

[…] Call Me Ishmael by Charles Olson. 1971 trade paperback by City Lights Books. No designer credited. Call Me Ishmael is a perfect book. […]

LikeLike

[…] Me Ishmael – Amanda learned about this book back in the spring. Then I read this review over at biblioklept. So naturally this was the first thing I read when the books arrived. So intense and so […]

LikeLike

[…] to be the central fact to man born in America,” declared Charles Olson in the beginning of Call Me Ishmael, his study of Melville’s whale. “I spell it large because it comes large here. Large, and without mercy.” The […]

LikeLike

[…] reinvent “sivilization.” As the poet-critic Charles Olson puts it in the beginning of Call Me Ishmael, “I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America. I spell it large because it […]

LikeLike

“When made his whale he made his god.”

I know you had it right before. Testing your readers?

Anyway, your posts are always a pleasure. You certainly know how to read.

LikeLike

It’s just poor old me with no copy editor! I read my reviews out loud and still can’t catch the typos. Thanks.

LikeLike