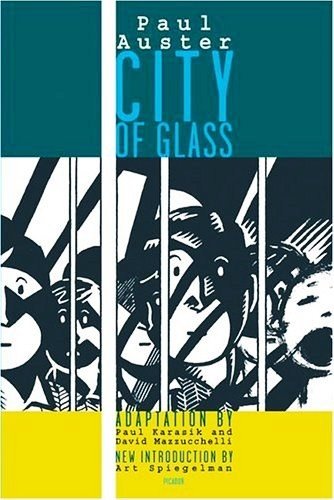

Paul Auster’s 1985 novel City of Glass explores doubling, shadowing, and what it means to wear another person’s skin, so it’s fitting that the book has its own doppelgänger in the form of a graphic novel by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli (maestro Art Spiegelman served as catalyst and counselor). I should admit upfront that although I’ve read a few of Auster’s books, I haven’t read City of Glass, considered by many to be his masterpiece. I have read Mazzucchelli’s excellent novel Asterios Polyp (and plenty of stuff by overseer Spiegelman), so the adaptation intrigued me. I wasn’t disappointed. I read Karasik and Mazzucchelli’s City of Glass in one brisk sitting and thoroughly enjoyed it. What’s it about?

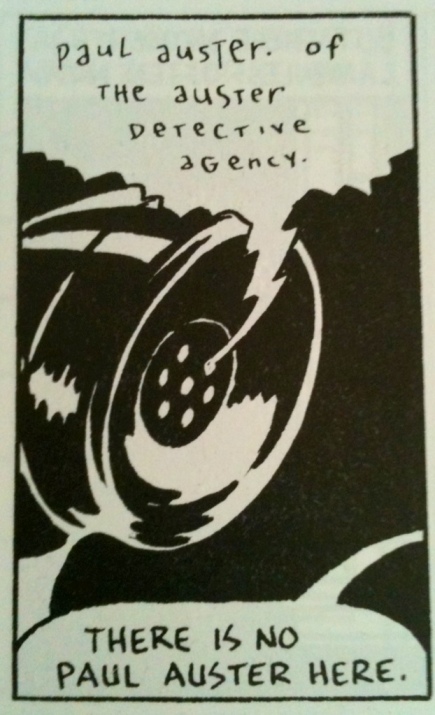

Okay, so there’s this novelist, Quinn (“rhymes with twin”), who, after the death of his wife and son, takes up writing boilerplate detective novels under the pseudonym William Wilson. Late in the book, Quinn (if he’s still Quinn at that point, which I’ll get to) identifies the pseudonym with the “real” name of NY Mets center fielder (and future coach) Mookie Wilson—but savvy readers will also recognize “William Wilson” as the name of an Edgar Allan Poe story about a man haunted by a doppelgänger of himself to the point that he goes insane. In the Poe story, Wilson and his doppelgänger (whose name is, of course, William Wilson as well) share the same birthday, January 19th, which also happens to be E.A. Poe’s birthday (and my brother’s too, although that is not germane to this review). Auster is clearly working from Poe’s story, although he never announces this explicitly (at least not in the comic-bookization). Arthur Hobson Quinn, for example, wrote an exhaustive biography of Poe (published in 1941). Crossing from the real to the fictional, from authorial to character, Auster inserts himself into the story from its outset. At the beginning of the book, protagonist Quinn gets a mysterious call, like something out of the noir novels he writes:

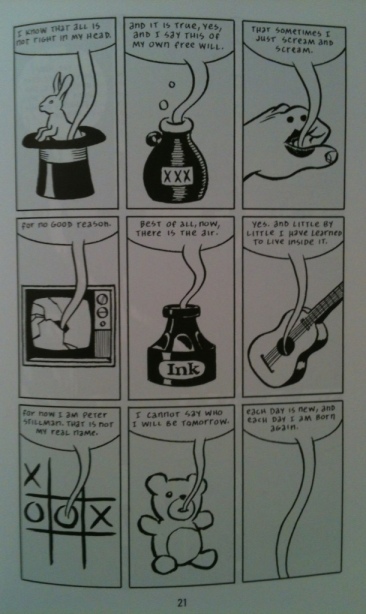

Bored, or perhaps ventriloquized by a force he doesn’t understand, Quinn takes up the identity of detective Paul Auster and agrees to take on a case for Peter Stillman, a man who, as a boy, suffered feralization at the hands of his insane father, who hoped to discover the Ur-language of god through the boy. Stillman’s monologue is one of the highlights of the book, showcasing the malleability of language—and also, significantly, the malleability of speakers:

Stillman hires Quinn/Auster to track his father, also named Peter Stillman (Peter is also the name of Quinn’s dead son). Actually, it’s Stillman the Younger”s wife/speech pathologist who hires Quinn/Auster; she’s certain that Stillman the Elder, freshly released from a mental asylum, will return to harm his son.

Quinn/Auster slides into the role of Max Work, his noir novel protagonist—or, perhaps more accurately, William Wilson’s noir protagonist—and begins tracking Stillman the Elder (or a version of Stillman the Elder—I won’t spoil the novel’s strangest, most maddening metaphysical gambit here). And, predictably, as Quinn/Auster/Wilson/Work shadows Stillman Sr., he morphs into yet another doppelgänger:

Quinn/Auster/Wilson/Work eventually confronts Stillman, and the pair have a series of fascinating conversations about language, Milton, Humpty Dumpty, and the Tower of Babel. The motifs and themes are telegraphed fairly straightforward here, but also communicated through a lens of madness that comes to dominate the book’s third act—an act that initiates in a meeting between Q/A/W/W and the “real” Paul Auster, a writer who’s working on an essay about the authorship of Don Quixote. The Don Quixote conversation is perhaps too overt, the sort of postmodern cleverness that I increasingly find a big turnoff, but it’s not clumsy or awkward. Still, there’s something mildly irritating about an author tipping his hand and then showing you how he’s tipping his hand.

The third act of City of Glass feels compressed, rushed even, and will definitely disappoint readers who wandered in for a detective stories, hoping for concrete answers and a neat and tidy plot. However, the book’s themes of fantasy and reality, play and work, sanity and madness, and character and author are rich if frustrating in their circuitousness. Mazzucchelli’s art is evocative and fitting, recalling at times the rough-hewn pop art of Raymond Pettibon and the traditional prowess of masters like Kirby and Eisner. (I’ll bring up Spiegelman again too, who introduces the volume. A friend of Auster’s, he brokered the project and oversaw its development, and his work as a creative director here is evident in the book’s cohesion). I imagine fans of Auster’s New York Trilogy, of which City of Glass is the first book, will be interested in checking this one out. Having come first to the graphic novel, I now look forward to reading its doppelgänger, Paul Auster’s City of Glass. Good stuff.

✌

LikeLike

I found the third act of the book disappointing, as if Auster had run out of ideas or, having had his fun with post-modern gimmickry, he couldn’t be bothered concluding the book in satisfying way.

LikeLike

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find many of your post’s to be just what I’m looking for.

Does one offer guest writers to write content to suit your needs?

I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write regarding here. Again, awesome web site!

LikeLike

[…] Some people find bits of it to be too clever: […]

LikeLike