Making a weekend trip from the east coast of Florida to its Gulf shores, my family and I listened to Nicol Williamson’s early 1970s recording of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Williamson’s recording is rich and expressive, his command of each voice bringing Tolkien’s characters to life.

I first heard Williamson’s recording over twenty years ago on a series of LPs that I checked out from the library. I had probably already read The Hobbit half a dozen times by then, but Williamson’s sonorous voice—along with the music and audio production effects—added another layer to Middle Earth.

My daughter, five, already familiar with the 1977 Rankin-Bass film, had no problem keeping pace with the story (although she occasionally asked me to pause for clarification on a few finer points, such as the delicate distinctions between goblins and trolls, or just who exactly is this guy Bard who shows up all of a sudden?) My favorite part of the entire weekend was my two year old imitating Gollum, sniveling a sinister, “My precious!” while squinting gleefully.

There are few books I’ve read as many times as Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy: I read it countless times between the ages of 11 and 15, read it again as an undergrad, then read it again–twice, I’m not ashamed to admit—when Peter Jackson’s adaptations came out. However, despite reading The Hobbit repeatedly as a kid, I’ve never really gone back to it. It traffics in a gentle folklore that seems out of square with the epic mythmaking in The Lord of the Rings, and I think that I was always unsettled by a certain discontinuity between the two books that was easier to ignore if I never went back to The Hobbit.

Memory has a way of eliding details, and books are especially susceptible to this wearing down and smoothing out. So, I remembered The Hobbit as a quest, a miniature epic with Bilbo Baggins leaving the comforts of home to find treasure guarded by the dragon Smaug. I remembered Gandalf and the thirteen dwarves invading Bilbo’s tidy hobbit hole; I remembered trolls who turn to stone; I remembered riddles with Gollum and a ring that turns its wearer invisible; I remembered Mirkwood and barrels and the mountain lair of a dragon. I vaguely remembered the Battle of Five Armies, where the enormous eagles literally swoop in and save the day, deus ex machina style.

Listening to the unabridged audio, I was struck by just how much had escaped my memory: I barely recalled the spiders of Mirkwood or the talking ravens or the part where the wargs tree the dwarves. I had completely forgotten the shapeshifter Beorn, a creature straight out of Scandinavian myth.

What I found most strange in revisiting The Hobbit though was its radical compression, its tendency and willingness to pivot sharply, to cast its characters about or trample them under (metaphorical and sometimes literal) foot, or throw them in dungeons or barrels or some other danger.

Whereas The Lord of the Rings progresses from the folkloric feel of The Shire through to the high-adventure sweep of Icelandic saga and ultimately to a King Jamesish condensation of near-pure archetypery (and back again, of course), The Hobbit showcases a rambling, flowing, discursive, “out of the frying pan, into the fire” rhythm.

In short, The Hobbit, as it turns out, is a picaresque novel.

And just what is a picaresque novel, and why is The Hobbit one?, you may or may not ask.

Michael Seidel offers a clear definition in his introduction to Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (an excellent picaresque, by the way):

. . . the tradition of Continental picaresque, or rogue, literature . . . became popular throughout Europe with the publication of Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) in Spain. Picarós and picarás are orphans, vagabonds, desperadoes, and reprobates trying to manipulate the conventions of a world largely determined by established family and class connections. . . . Picaresque fiction is the story of outsiders trying to get in, and the fortunes of the protagonist often depend on adaptable, protean, and duplicitous behavior as picaresque characters become who they need to be to survive.

The Hobbit is very much the story of the topsy-turvy turns of Bilbo Baggins’s identity. At the adventure’s outset, he’s a respectable—comfortable—Baggins of Bag End. Not the sort of fellow who goes on adventures. And yet he’s enlisted by Gandalf to serve as burglar for the expedition, a picaró in the making who steals a purse from a troll and never looks back.

It’s not just Bilbo’s various thefts, but also his “adaptable, protean, and duplicitous behavior” that marks him as a picaró. His scheming is evident repeatedly in the novel, whether he’s riddling with Gollum or Smaug, devising a breakout from the Elf King of Mirkwood’s dungeon, or playing the long con against the parties involved in the Battle of Five Armies. He echoes Gandalf in this way, whose talents seem to veer more toward trickery and cunning than dazzling spells or marvelous magic.

Bilbo’s picaresque turns of fortune and turns of identity are neatly summarized in a late exchange with yon dragon Smaug, who immediately calls him out as a picaró:

“You have nice manners for a thief and a liar,” said the dragon. “You seem familiar with my name, but I don’t seem to remember smelling you before. Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?”

“You may indeed! I come from under the hill, and under hills and over the hills my paths led. And through the air, I am he that walks unseen.”

“So I can well believe,” said Smaug, “but that is hardly our usual name.”

“I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I am chosen for the lucky number.”

“Lovely titles!” sneered the dragon. “But lucky numbers don’t always come off.”

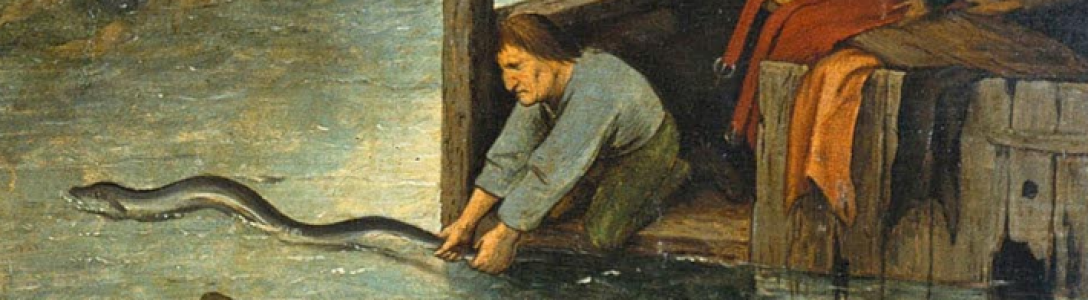

“I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me.”

“These don’t sound so creditable,” scoffed Smaug.

“I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; and I am Barrel-rider,” went on Bilbo beginning to be pleased with his riddling.

“That’s better!” said Smaug. “But don’t let your imagination run away with you!”

But imagination is of course the primary tool of the picaró, and Bilbo is no slouch: The Hobbit condemns evil, greedy Smaug when it shows the rewards of letting “your imagination run away with you.” Indeed, the entire novel is a running away, a constant deflection of stable identity, as Bilbo twists and turns his way back to The Shire.

And what happens to Bilbo? What happens to that once-stable, once-comfortable identity? We learn at the novel’s end about the queering of his identity—

. . . he had lost his reputation. It is true that for ever after he remained an elf-friend, and had the honour of dwarves, wizards, and all such folk as ever passed that way; but he was no longer quite respectable. He was in fact held by all the hobbits of the neighbourhood to be ‘queer’—except by his nephews and nieces on the Took side, but even they were not encouraged in their friendship by their elders. I am sorry to say he did not mind.

So! Queer, strange Baggins the picaró embraces his “Took side,” his disreputable adventuring side. And still the narrative comes to a lovely cozy warm respectable ending, Bilbo’s identity transformed, sullied, illuminated, and enlarged by his picaresque adventure.

And the picaresque? Well, maybe I’ve stretched its definition a bit simply because I’m so fond of picaresque narratives these days. Maybe I’ve simply revisited a childhood classic and imposed a new viewpoint upon it. (And maybe years and years from now I’ll revisit it again with grandchildren, and find something new and different there as well. I hope).

I think what I enjoyed most about The Hobbit this time was hearing the rambling discursiveness of it all—here we have a narrative that understands the perilous and precarious position of the storyteller, he or she who might lose the thread—or worse, lose the audience!—at any damn time. So keep the story sailing, shifting, rambling out into new moods, modes, movements.

Seidel gives us a lovely definition of picaresque above, but can’t do better than Ralph Ellison who, in describing his modernist classic Invisible Man, offers us a description of the picaresque as “one of those pieces of writing which consists mainly of one damned thing after another sheerly happening.”

And this is the power of The Hobbit—which is to say the staying power of The Hobbit—its ability to evoke the imaginative force of one damned thing after another sheerly happening for generation after generation.

Very interesting, and good points.

LikeLike

[…] Read thе original post: Thе Hobbit Reconsidered аѕ a Picaresque Novel | biblioklept […]

LikeLike

What picaresque narratives would you recommend? It’s another stretch of the genre (which may be stretching that term) but my favorite is The Ordways by William Humphrey.

LikeLike

I’ll take the Humphrey as a recommendation.

I use the term loosely. I mean, clearly Don Quixote is the big picaresque, I suppose.

But I think Suttree and Blood Meridian both fit the bill, as does Voltaire’s candide. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. The Sot-Weed Factor. Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat. Huck Finn. The Savage Detectives, to an extent. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Moll Flanders. Much of Dickens.

Other suggestions, people?

LikeLike

I hope you read it. Love to hear what you think. I’m a big fan of Humphrey in general and that’s one of my favorites.

Joseph Andrews is an oldie, but I liked that, too.

LikeLike

_The Travels of Jaime McPheeters_, which won the Pulitzer Prize for literature in 1956. It’s by Robert Lewis Taylor.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Mark Geoffrey Kirshner.

LikeLike

[…] The Hobbit Reconsidered as a Picaresque Novel […]

LikeLike

[…] also revisited The Hobbit this year and somehow decided it’s a picaresque novel. Definitely a picaresque: Blood Meridian, which I reread as well. In fact, I’ve reread it at […]

LikeLike

[…] The Hobbit Is a Picaresque Novel […]

LikeLike

[…] The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit (a book I’ve always loved). I’ve preserved the reviewers’ own styles of punctuation and spelling. More one-star Amazon […]

LikeLike

[…] J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, as read by Nicol Williamson […]

LikeLike