- Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tale “The Birth-Mark” — or is it “The Birthmark”? — has been a favorite story of mine for years despite (or maybe because of) its being so damn symbolically overdetermined.

-

Or perhaps you want a quick summary—a refresher—okay:

Aylmer, “a man of science,” has this totally hot wife Georgiana—only she’s got a birthmark on her cheek, a small red mark that resembles a tiny hand—and it drives our scientist mad—so mad that he determines to make her perfect by removing the mark. Tragic ending ensues.

- One of the reasons I like “The Birth-Mark” so much is that it so clearly limns the futility of idealism.

Aylmer’s driving desire for mastery over Nature (echoing Shelley’s Frankenstein): the desire to “lay his hand on the secret creative force and perhaps make new worlds.”

The word “God” does not appear in “The Birth-Mark.”

But of course gods and creators are repeatedly invoked.

One such creator is Hawthorne’s friend Hiram Powers, whose sculpture Eve Tempted is invoked (invoking that other creator, the one who made a garden . . . )

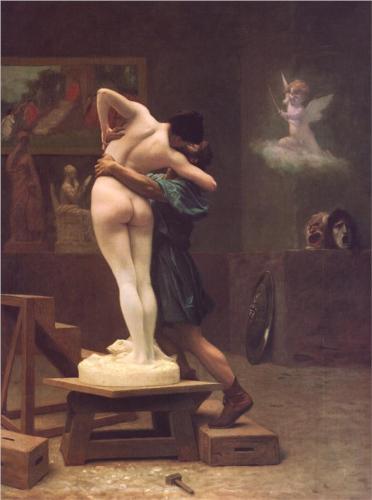

- And Pygmalion—

Aylmer, having convinced his wife that he’ll erase her mark: “Even Pygmalion, when his sculptured woman assumed life, felt not greater ecstasy than mine will be!”

- Aylmer’s plan is shameful. It’s based on an obsessive misreading of the symbolism of his wife’s birthmark. We’re told that Aylmer “select[s] it as the symbol of his wife’s liability to sin, sorrow, decay, and death, Aylmer’s sombre imagination was not long in rendering the birthmark a frightful object, causing him more trouble and horror than ever Georgiana’s beauty, whether of soul or sense, had given him delight.”

He’s a very poor reader. His judgments are overawed by idealism.

- Georgiana asks him: “Cannot you remove this little, little mark, which I cover with the tips of two small fingers?”

On one level, Georgiana is offering her husband the opportunity to play doctor with her, to get rid of the mark that’s driving him mad—but I think there’s an ironic second meaning at work here as well. I think she’s suggesting that he remove his perception of the mark, his reading of the mark. That he change his attitude.

- Hawthorne’s homeboy Herman Melville, in his big book Moby-Dick, has Ishmael point out—in a simple, charming, homey way—that there is no simply no ideal purity available to us:

We felt very nice and snug, the more so since it was so chilly out of doors; indeed out of bed-clothes too, seeing that there was no fire in the room. The more so, I say, because truly to enjoy bodily warmth, some small part of you must be cold, for there is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast. Nothing exists in itself. If you flatter yourself that you are all over comfortable, and have been so a long time, then you cannot be said to be comfortable any more.

13. Actually, even though we’re told he’s brilliant, it turns out that Aylmer is not the transcendent scientist he’d like to be. In a scene that almost edges into comedy (just a dab to give this tragedy dimension), Georgiana reads

a large folio from her husband’s own hand, in which he had recorded every experiment of his scientific career, its original aim, the methods adopted for its development, and its final success or failure, with the circumstances to which either event was attributable. The book, in truth, was both the history and emblem of his ardent, ambitious, imaginative, yet practical and laborious life. He handled physical details as if there were nothing beyond them; yet spiritualized them all, and redeemed himself from materialism by his strong and eager aspiration towards the infinite. In his grasp the veriest clod of earth assumed a soul. Georgiana, as she read, reverenced Aylmer and loved him more profoundly than ever, but with a less entire dependence on his judgment than heretofore. Much as he had accomplished, she could not but observe that his most splendid successes were almost invariably failures, if compared with the ideal at which he aimed. His brightest diamonds were the merest pebbles, and felt to be so by himself, in comparison with the inestimable gems which lay hidden beyond his reach. The volume, rich with achievements that had won renown for its author, was yet as melancholy a record as ever mortal hand had penned. It was the sad confession and continual exemplification of the shortcomings of the composite man, the spirit burdened with clay and working in matter, and of the despair that assails the higher nature at finding itself so miserably thwarted by the earthly part. Perhaps every man of genius in whatever sphere might recognize the image of his own experience in Aylmer’s journal.

- I should clarify, perhaps, that Georgiana reads the journal as she waits out Aylmer’s experiments in his laboratory.

-

Oh, gosh, I almost forgot—there’s a third player in this piece, Aminadab, Aylmer’s manservant/lab assistant, who’s described throughout the text (usually by Aylmer) as “clod,” “man of clay,” “human machine,” “earthly mass,” “thing of the senses” — he’s the pure-material to contrast Aylmer’s (would-be) pure-spirit. Although he’s not described as hunchbacked I can’t help but see him that way, this Igor to a Hollywood Frankenstein. And he laughs.

-

Aminadab laughs at Aylmer’s folly. Here is the conclusion of this story:

Alas! it was too true! The fatal hand had grappled with the mystery of life, and was the bond by which an angelic spirit kept itself in union with a mortal frame. As the last crimson tint of the birthmark—that sole token of human imperfection—faded from her cheek, the parting breath of the now perfect woman passed into the atmosphere, and her soul, lingering a moment near her husband, took its heavenward flight. Then a hoarse, chuckling laugh was heard again! Thus ever does the gross fatality of earth exult in its invariable triumph over the immortal essence which, in this dim sphere of half development, demands the completeness of a higher state. Yet, had Alymer reached a profounder wisdom, he need not thus have flung away the happiness which would have woven his mortal life of the selfsame texture with the celestial. The momentary circumstance was too strong for him; he failed to look beyond the shadowy scope of time, and, living once for all in eternity, to find the perfect future in the present.

17. I won’t comment any further on the story, other than to suggest that the final two lines—in bold above—seem perfectly sensible and wonderfully wise to me. I think Wittgenstein may have been approaching a similar idea some eighty years later in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in the way in which our visual field has no limits.

I loved this review! Very well thought out and responded to :) Would you agree with me to say that Alymer is driven by the insanity much like Shakespeare’s character of Othello regarding the symbol of the handkerchief to the birthmark, as the “symbol of his wife’s liability to sin, sorrow, decay, and death”?

LikeLike

“Trifles light as air / Are to the jealous confirmations strong / As proofs of holy writ” — Yeah, I definitely see a connection there. The handkerchief to is red, spotted with strawberries—I’ve always taken the handkerchief to be a symbolic substitution for the wedding sheets (white with a red blood stain), a mark of experience (and thus loss of innocence).

LikeLike

I’d never read the story before, and loved reading it alongside your review. Thanks!

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

I’ve always loved this story, too, overdeterminedness and all. I like that you zero in on Aylmer-as-poor-reader. I used to teach this story in first-year Intro to Lit classes, and one angle from which to read it is as a tale about reading, or more accurately, misreading, and one can even take it further, into the realm of deconstructionism, as a discourse on the undeterminability of signs and texts. So, though Aylmer seems to read the birthmark incorrectly, in his defense, it’s not an easy thing to read. I mean, a tiny red hand? That could go almost as many different ways as there are readers (though of course the text provides other cues to nudge the careful reader toward a particular reading). But look at Georgiana’s reading of the journal too–again, a case of vastly different readings.

But that’s just one approach, really. I like that you’ve explored so many different possibilities!

LikeLike

Thanks, Juju!

LikeLike

Fear not.

LikeLike

Great review! I too love this story for so many reasons. This story is even more relevant today than it was in Hawthorn’es time. Having a 14 year-old daughter who sees the photo shopped, airbrushed, perfect bodies of models in all media formats is cause for concern. Women will go to such lengths for beauty that they never notice what beauty really is.

LikeLike

Nice connection—yeah, the story is absolutely as relevant as ever, as young girls develop eating disorders (and other problems) in trying to attain an “ideal” condition.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Mary Beth Bass.

LikeLike