In his introduction to Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita, Richard Pevear (who translated the book with Larissa Volokhonsky) notes

the qualities of the novel itself — its formal originality, its devastating satire of Soviet life, and of Soviet literary life in particular, its ‘theatrical’ rendering of the Great Terror of the thirties, the audacity of its portrayal of Jesus Christ and Pontius Pilate, not to mention Satan.

Pevear also offers a concise (if mechanical) summary:

The novel in its definitive version is composed of two distinct but interwoven parts, one set in contemporary Moscow, the other in ancient Jerusalem (called Yershalaim). Its central characters are Woland (Satan) and his retinue, the poet Ivan Homeless, Pontius Pilate, an unnamed writer known as ‘the master’, and Margarita. The Pilate story is condensed into four chapters and focused on four or five large-scale figures. The Moscow story includes a whole array of minor characters. The Pilate story, which passes through a succession of narrators, finally joins the Moscow story at the end, when the fates of Pilate and the master are simultaneously decided.

As you might gather from its translator’s descriptions, there’s a lot going on in The Master and Margarita.

Bulgakov satirizes early Soviet life, particularly focusing on the phonies and fops who populate Moscow’s art scene. This aspect of the narrative is full of disappearances; characters are taken away forever by the secret police. Bulgakov elides the secret police from the reader, a brilliant rhetorical move that heightens the book’s paranoia. The paranoid comedy edges quickly into horror though as the reality of living in such confined spaces and under such controlled surveillance bleeds into Bulgakov’s fantasy.

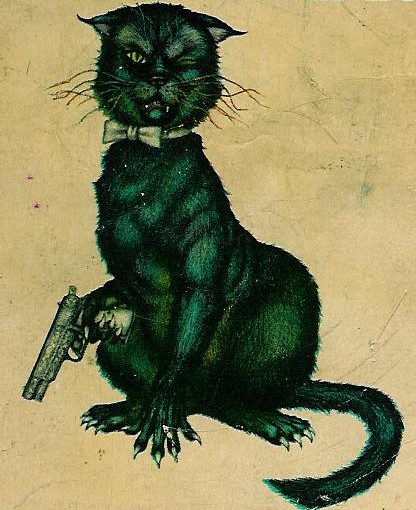

Indeed, the realities of life in the Soviet police state (“No papers, no person”) come across as far scarier than the supernatural characters of The Master and Margarita. Woland’s retinue, in particular his cat Behemoth (who seems to grace—can that be the right verb?—the covers of most editions of the novel), imbue the novel with a compelling manic energy. The most memorable sequences for most readers will likely involve Woland’s troupe’s antics, including their wild performance at the Variety Theatre, which climaxes in this bit of comic violence before culminating in a rush of greed and gratuitous nudity:

And an unheard-of thing occurred. The fur bristled on the cat’s back, and he gave a rending miaow. Then he compressed himself into a ball and shot like a panther straight at Bengalsky’s chest, and from there on to his head. Growling, the cat sank his plump paws into the skimpy chevelure of the master of ceremonies and in two twists tore the head from the thick neck with a savage howl.

The two and a half thousand people in the theatre cried out as one. Blood spurted in fountains from the torn neck arteries and poured over the shirt-front and tailcoat. The headless body paddled its feet somehow absurdly and sat down on the floor. Hysterical women’s cries came from the audience. The cat handed the head to Fagott, who lifted it up by the hair and showed it to the audience, and the head cried desperately for all the theatre to hear:

‘A doctor!’

(Don’t worry, Bengalsky gets his head back. Sort of).

Another highlight of the book is the Walpurgis Night episode—Chapter 23, “The Great Ball at Satan’s”—which I’d argue can stand on its own, free of context, as a lovely, dark, bizarre short story. Margarita plays hostess to a seemingly-endless parade of “kings, dukes, cavaliers, suicides, poisoners, gallowsbirds, procuresses, prison guards and sharpers, executioners, informers, traitors, madmen, sleuths, seducers,” who arrive via fireplace, their corpses reanimated to take part in the grand dance. Bulgakov cribs freely from history, populating the episode with condemned persons obscure and infamous alike.

The Walpurgisknacht episode highlights The Master and Margarita‘s strong Easter/Faust theme, which plays out for several characters who are reborn (figuratively or otherwise). The least interesting of these by far is the master himself. But perhaps this is unfair. It’s entirely plausible that the master is the storyteller of The Master and Margarita. In any case, his unnamed novel (within the text) depicts an alternate version of Jesus of Nazareth’s crucifixion, and it’s here that we find what I take to be The Master and Margarita’s most interesting and complex character, “the fifth procurator of Judea, Pontius Pilate.” The episodes with Pilate (who employs his own secret police, a wonderful parallel to the Soviet setting) offer a kind of moral ballast to the supernatural sequences, which fluctuate between manic-comic anxiety and big-R Romanticism. Of all the souls in turmoil in The Master and Margarita’s, I found the depiction of Pilate’s troubles the most profound.

The Master and Margarita’s lurching structure threatens narrative coherence until the novel’s final moments, when the master meets his creation. The moment is unexpectedly poignant, and does much to amend some of the novel’s ungainliness. The middle sections in particular get bogged down, as Bulgakov subjects his Muscovite extras to all sorts of fates (some more terrible than others). While some of these episodes are funny, and they certainly give the book some of its satirical power, they ultimately read as variations on a theme. I found my eyes glazing over in the novel’s epilogue when Bulgakov decides to check in on the survivors.

I’ve failed to remark on so much of The Master and Margarita, and I’m certain that much of its rich allusive texture was lost on me. (I should point out here how helpful the end notes of my edition were). Persons interested in early Soviet life who have not yet found their way to Bulgakov’s novel will wish to do so (as well as the work of Bulgakov’s contemporary Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky); the novel also makes a strange but worthy companion piece to William Gaddis’s enormous Faust tale The Recognitions. Although The Master and Margarita sags at times, at its finest moments—of which there are many—it is funny, dark, and engrossing.

It’s my favorite novel, but admittedly, I am not a worthy critic. I don’t like most Literature with a capital L. And I was a Russian and Soviet Studies major in college, meaning that for one thing I love it simply as a lifelike illustration of a familiar history (the bizarre horrors of the early Stalinist period). It is one thing to read history books about the intellectual and artistic culture and controls of that time and another to read the novel.

While the book does drag a bit under its own weight in the middle, I think that it also delights more than your review may make clear for some readers. I think that people who like fantastical novels in general could enjoy much of it simply for those ridiculous delights. Not only the heights like the Variety Theatre performance, but the cutting humor of Woland and his cohorts’ interactions with the human beings trying in various ways to make lives in the Hellish reality of that time. And the juxtaposition of all of that wonderful nonsense with the figure of Pilate, and his headaches, and his conflictedness. It’s just…really something. You can always skim the middle parts if you tire of them. :-)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on thegooners16 and commented:

Michael Bulgakov’s Novel

LikeLike

I’m not sure that it drags in the middle, but as a samizdat novel, it was a labour of love where Bulgakov could indulge himself, free of critical and official constraints on his writing. A much tighter novel is A Dog’s Heart, but it lacks the baroque glory of The Master of Margarita. I did a review of them both on my blog too a few months back: http://alastairsavage.wordpress.com/2013/05/01/mikhail-bulgakov-when-the-devil-came-down-to-moscow/

Love that picture of Behemoth!

LikeLike

Behemoth is one cool cat dude. Must be a Russian relative of the Furry Freak Brothers cat.

LikeLike

Many books lose much of their linguistic beauty in translation, perhaps, this book is one of them. It has been torn into quotes that live the life of their own in the Russian language today. Apart from its linguistic beauty, the novel is often misunderstood for satire on the early Soviet life, In fact, it is a book about the repeating biblical story of betrayal that can be redeemed through love only. Pilatus betrayed Jesua, and Master betrayed his book (that doesn’t burn, as it turns out and resurrects, just like Jesua). And it was the love of Margarita that saved Master at the end. Perhaps, its satirical “nature” prevents many readers from seeing beyond just the ethnographic detail, with which it is so rich)

LikeLike

[…] Mikhail Bulgakov’s Novel The Master and Margarita Reviewed (biblioklept.org) […]

LikeLike

[…] Mikhail Bulgakov’s Novel The Master and Margarita Reviewed (biblioklept.org) […]

LikeLike

[…] Mikhail Bulgakov’s samizdat Soviet-era novel Master and Margarita has improved in my memory; reviewing my review of it a few years ago, I find that I remember it fondly, and stronger. (I wrote … […]

LikeLike

[…] the more. I liked The Heart of a Dog more than Bulgakov’s posthumously-published classic, The Master and Margarita. I had a rough idea of Master’s plot, whereas my ignorance of the events in The Heart of a […]

LikeLike