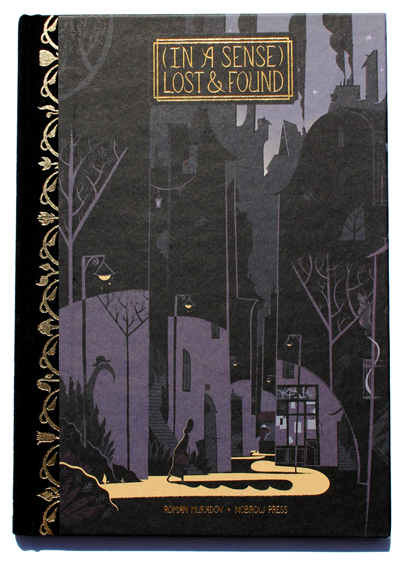

I’ve been a fan of Roman Muradov’s strange and wonderful illustrations for a while now, so I was excited late this summer to get my hands on his début graphic novella, (In a Sense) Lost and Found (Nobrow Press). In my review, I wrote: “I loved Lost and Found, finding more in its details, shadowy corners, and the spaces between the panels with each new reading.” The book is a beauty, so I was thrilled when Roman agreed to discuss it with me over a series of emails. We also discussed his influences, his audience, his ongoing Yellow Zine projects, his recent cover for Joyce’s Dubliners, and his reaction to some of the confused Goodreads reviews his novella received. Check out Roman’s work at his website. You won’t be disappointed.

Biblioklept: When did you start working on (In a Sense) Lost and Found? Did you always have the concept kicking around?

Roman Muradov: The idea came to me in 2010 in the form of the title and the image of a protracted awakening. I wrote it as a short story, which had a much more conventional development and actually had some characters and plot movements, all of them completely dropped one by one on the way to the final version apart from the basic premise. I didn’t have a clear understanding of what was to be done with that premise, but the idea kept bothering me for some time, until I rewrote it a few times into a visual novella when Nobrow asked me if I wanted to pitch them something. Since then it went through several more drafts and even after everything was drawn and colored I had to go back and edit most of the dialogues, which is a nightmarish task in comics, since it involved re-lettering everything by hand.

Biblioklept: When you say you wrote it as a short story, I’m intrigued—like, do you mean as a sketch, or a set of directions, or as a tale with imagery? Part of the style of the book (and your style in general) is a confidence in the reader and the image to work together to make the narrative happen. When you were editing the dialogues, were you cutting out exposition, cues, contours?

RM: No, I mean a traditional pictureless short story. I was struggling with forms at the time and didn’t feel confident with any of them. In a way this still persists, because my comics are often deliberately deviating from the comics form, partially in my self-published experiments. The story itself was still ambiguous, I never considered showing what she lost, or how. With time I edited down all conversation to read as one self-interrupting monologue.

Biblioklept: I want to circle back to (In a Sense) Lost and Found, but let’s explore the idea that your work intentionally departs from the conventions of cartooning. When did you start making comics? What were the early comics that you were reading, absorbing, understanding, and misunderstanding?

RM: I came to comics pretty late; I only discovered Chris Ware & co around 2009. As a child I spent one summer drawing and writing little stories, ostensibly comics, then I stopped for a couple of decades. I’m not really sure why I started or stopped. In general my youth was marked by extraordinary complacency and indifference. I followed my parents’ advice and studied petroleum engineering, then worked as a petroleum engineer of sorts for a year and a half, then quit and decided to become an artist. I still feel that none of these decisions were made by me. Occasionally certain parts of my work seem to write themselves and I grow to understand them much later, which is weird.

Biblioklept: Was Ware a signal figure for you? What other comic artists did you find around that time?

Ware, Clowes & Jason were the first independent cartoonist I discovered and I ended up ripping them off quite blatantly for a year or so. Seth was also a big influence, particularly his minute attention to detail and his treatment of time, the way he stretches certain sequences into pages and pages, then skips entire plot movements altogether. Reading Tim Hensley’s Wally Gropius was a huge revelation, it felt like I was given permission to deviate from the form. Similarly, I remember reading Queneau’s “Last Days” in Barbara Wright’s translation, and there was the phrase “the car ran ovaries body” or something like that, and I thought “oh, I didn’t know this was allowed.”

Biblioklept: Your work strikes me as having more in common with a certain streak of modernist and postmodernist prose literature than it does with alt comix. Were you always reading literature in your petroleum engineer days?

RM: That’s certainly true, nowadays I’m almost never influenced by other cartoonists. I wasn’t a good reader until my mid-twenties, certainly not back in Russia. I stumbled upon Alfred Jarry (not in person) while killing time in the library, and then it was a chain reaction to Quenau, Perec and Roussel, then all the modernists and postmodernists, particularly Kafka, Joyce, Nabokov and Proust.

Biblioklept: How do you think those writers—the last four you mention in particular—influence your approach to framing your stories?

RM: From Nabokov I stole his love for puzzles and subtle connections, a slightly hysterical tone, his shameless use of puns and alliteration, from Kafka–economy of language and a certain mistrust of metaphors–it always seems to me that his images and symbols stretch into an infinite loop defying straightforward interpretation by default, from Joyce and Proust the mix of exactitude and vagueness, and the prevalence of style over story, the choreography of space and time. I should’ve say “I’m in the process of stealing,” I realize that all of these things are far too complex, and I doubt that I’ll ever feel truly competent with any of these authors as a reader, let alone as a follower.

Biblioklept:(In a Sense) Lost and Found begins with a reference to Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and then plunges into a Kafkaesque—to use your phrasing—“infinite loop defying straightforward interpretation.” How consciously were you following Kafka’s strange, skewed lead?

RM: I wanted the reference to be as obvious as possible, almost a direct copy, as if it’s placed there as an act of surrender–I’m not going to come up with a story, here’s one of most famous opening lines that you already know. Usually I know the beginning and the ending and I often downplay their importance, so that the work becomes focused mostly on the process and so that readers don’t expect any kind of resolution or satisfactory narrative development. In the password scene the phrases are copied directly from Eliot’s Wasteland, which itself refers to Paradise Lost in these passages. It’s a bit like a broken radio, shamelessly borrowing from the narrator’s visual and literary vocabulary, the way it happens in a dream.

Biblioklept: I’m reminded here of “always already” — a phrase itself attributed variously to Marx, Heidegger, Derrida, Ricouer et al. — that communication is possible because it’s (always) already mediated by signs and symbols. I know you just finished reading Tom McCarthy’s novel C. When he was doing interviews for the novel, he claimed that what he was doing was “simply plugging literature into other literature.” (In his 2012 essay “Transmission and the Individual Remix,” he argues that this “plugging in” is both tradition and counter-tradition to all narrative formation).

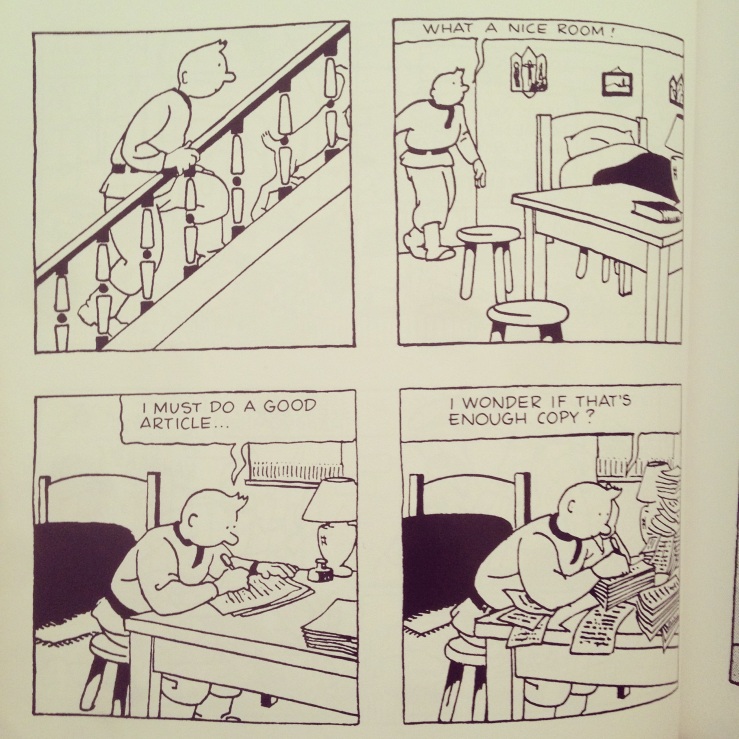

RM: Right, or “there are only other books,” I think it’s Derrida’s, though I’m not sure. I wasn’t aware of McCarthy when I was working on (In A Sense) so I certainly I wasn’t expecting to find another book heavily referencing both Tintin and Kafka. It’s a somewhat unusual combination, although it makes a lot of sense to me. I’ve always been attracted to Tintin’s intense anonymity. He’s practically sexless, pretty good at everything from guns to airplanes, yet he’s a complete failure as his character, in his role of a journalist. He attempts to write only once and immediately gives up. Of course there’s an explanation for that, the young readers would be bored by panels showing the hero writing reports, but this missing part is what really interests me. So I put Premise into his plusfours, literally, making her look “tintinnabulatingly decent” and wanted to explore the dark side of the an imposed role.

The whole idea of transmission without control from the author appeals to me greatly. I didn’t completely understand that password page with “sylvan scene” and “lean solicitor” when I drew it, but I inexplicably felt confident that it should have this exact layout, pacing and words. Now that I look at it in printed form it makes perfect sense to me, the reversed order of question-password, the setting and the actual words.

Biblioklept: Charles Burns plugged Tintin into Burroughs’s Interzone in his X’ed Out trilogy. Have you read those?

RM: I just read Sugar Skull last week, now I need to find the first two and reread them in order. Burns often refers to his experience of reading Tintin as a child without completely understanding the story and making his own sense out of the pictures (I may be misremembering this), and in the trilogy the act of reading is always an active one. There’s also a great wealth of cultural and artistic references feeding into the images and story, and I love how open and direct the treatment is. Unlike Burroughs, Burns is completely in control of the disjointed narrative and that creates an wonderful claustrophobic atmosphere, further heightened by his brushwork and coloring.

Biblioklept: Is your description of how the password scene came about indicative of your process in general? How intuitive is your process?

RM: I suppose it’s a mix of accident and design, although my process is far less intuitive nowadays, because I have a pretty clear idea of what I’m trying to do. Almost everything I write is entirely logical, I never allow myself to insert any phrase or image for the sake of prettiness or emotional impact. There’s a cultish admiration of honesty and self-expression nowadays, particularly in comics, and I’m very much going against that. It may be because I’m a fairly sentimental person myself, so Eliot’s idea of “escape from personality” appeals to me a great deal. Also, artistic anonymity is hardly possible, it seems to me that in a haphazard arrangement of stolen quotes the artist expresses herself much more clearly than through a deliberate outpouring of emotions. The only time someone told me that they “related” to my work was actually last week at SPX; a young woman said she likes to drink hot water instead of tea or coffee like a character of my strip, who considers it a gesture of austerity at a Sunday brunch.

Biblioklept: When you note a “cultish admiration of honesty and self-expression” in comics, are you referring to the glut of confessional stuff out there?

RM: Right, although it extends far outside comics. I get really annoyed when radio interviewers ask novelists if their personal life is somewhere in the book and how much of the plot is “real.” Independent comics is still a pretty young medium, and as with all such things the most radically innovative work often appears at the very beginning (Tristram Shandy/Krazy Kat), then there’s a period of platitude, then the local modernism emerges in response to the local 19th century novel. At the same time I’m weirdly attracted to all these platitudes, or rather the Gogolian concept of poshlust, probably my favorite Russian word, for its untranslatability and its deep connection to the language and the place (not to mention the punny English spelling). So, for instance, a great deal of (In A Sense) was inspired by the sudden widespread acceptance and commodification of banal nostalgia, self-expression & personal experience, which I see as a kind of torpid mass hysteria. The initial spark for most of my work is entirely satirical, to which I later add other layers.

Biblioklept: I think that nostalgia has always been a big part of American culture—maybe culture in general—I mean, maybe nostalgia is key to how a culture maintains itself. But it seems like social media in particular has allowed for nostalgia to be combined with “self-expression” to new levels of saturation.

The satire in (In a Sense) is very subtle, oblique even—the work resists the kind of allegorical neatness that satire often rests on.

RM: Definitely, and this nostalgia of course very tightly linked with the current brand of consumerism. The concept is not new, but the consumer has never had so much power in her hands, which is both frightening and fascinating.

As for satire, I feel that like plot, characters or metaphors it should be taken with suspicion as events and trends become rapidly irrelevant and pass out of vogue. Again, I’m rereading Dead Souls right now, and it doesn’t feel at all like the satirical epic that our Russian teacher told us it was–Gogol’s indignation is taken deep into his personal hell that’s thoroughly disconnected from the outside reality. And I love that rant against imaginary critics and relatable authors right in the middle of the book, how weird is that!

Most importantly, I touch upon the things that irritate me precisely because I don’t imagine myself having any significant cultural impact through art or satire. This idea of a fundamentally futile struggle, a battle that’s lost by default is very liberating and appealing to me artistically, it allows me to explore these matters, rather than point at them and try to make them go away. Even more importantly, I’m not immune to everything we’ve been talking about and I don’t know who is. Joyce carefully read all reviews of Dubliners and even took the trouble to write to the authors. Personally, I don’t think that me tweeting about a review of my work or an interview I recently did is in any way more dignified than a 12-year-old’s selfie. So when I work with themes of commodification and vanity, they’re very much my own and the target is effectively myself.

One of the earliest ideas for the book was a keychain version of Proust’s madeleine that literally buzzes when it’s dunked in tea, and it’s still there, although only in one or two panels. I can easily imagine how the premise and the entire story could be redone into a young-adult magical realism story with a cozy conclusion, but it’s more fun for me to focus on the stuff that’s usually left between the panels, the character getting on a bus for instance (three times). I have no interest in showing that keychain dunked, I’m much more invested in the shifts of color between panels, the rhythms and patterns of repetition and all such boring things.

Biblioklept: A quick scan over Goodreads shows a lot of bewilderment—even in the positive reviews. (The stock phrase “over my head” appears in three of the seven reviews currently posted). Were you ever tempted to compose a “young-adult magical realism story with a cozy conclusion”?

RM: My favorite goodreads review is “The problem with this book is that it went right over my head. Actually, that could be a problem with me…” I may misremember, but I think Flann O’Brien plugged a friend’s comment on his work-in-progress into At-Swim-Two-Birds, I might do something similar with this review. (In A Sense) must’ve gotten into the hands of very young librarians/reviewers (I’m completely oblivious to the whole YA world and I don’t really know how these things work) who were predictably bewildered by what on the surface looks like a normal comic book. Just because there are no genitals and naughty words it doesn’t make it a YA title, so it wasn’t my intention to confuse any teenagers. And no, my target audience is myself and I don’t think that approach is egoistic–writing for a target audience excludes a far greater number of people who don’t fall into that group, while writing for myself is effectively writing for anyone. Also, there was far more obscure stuff in the previous drafts and far greater density in writing, in fact I was a bit worried that the final version would feel a bit overexplained.

Biblioklept: I like that you brought up At Swim-Two-Birds—there’s a section where the narrator sums up a lot of what we’ve been talking about: “Characters should be interchangeable as between one book and another. The entire corpus of existing literature should be regarded as a limbo from which discerning authors could draw their characters as required, creating only when they failed to find a suitable existing puppet.” I think this insight is probably obvious to most writers, but a lot of readers expect (what they think is) originality. How does your work interrogate originality and authenticity?

RM: As with C, I read At Swim-Two-Birds after (In A Sense) was in a fairly finished state (apart from several pages and panels that I redrew/rewrote last year) but yes, this passage had a profound effect on me. Perhaps not as direct influence, but rather as confirmation of everything I believed but felt uneasy to admit even to myself.

I see originality and authenticity as rather meaningless constructs, continuously shoveled into our faces from every outlet. People always tell me that my work unlike anything else currently produced, and yet I make a point of stealing more obviously than artists usually allow themselves to. Most importantly, it’s all about treatment for me. If you ignore the style, nothing really happens in my stories, it’s the same modernist concept of extraordinary treatment of the ordinary, style is substance etc. I engage in deliberate suppression of personality because I know it’s ultimately futile–no matter how repetitive and disconnected I want my work to be, the warmer sides of my personality will leak through and I’d much rather have it admitted that way, than spell anything out in plain words or put conscious effort into making something unique. Perec’s Life A User’s Manual can be seen as a celebration of futility, among many other things, and it the most touching and uplifting book I’ve read despite all its constraints and lists.

As for the authenticity of experience, it’s given no room at all–I didn’t leave any hints on what (if anything) happened to Premise, that question is of no relevance, since the entire story is fed directly through her perception and has no place for objective reality. If she wakes up and sees it as lost, then it’s lost.

Biblioklept: The strips in your comic Yellow Zine demonstrate that principle of style-as-substance. How did you start Yellow Zine? Where does the name come from?

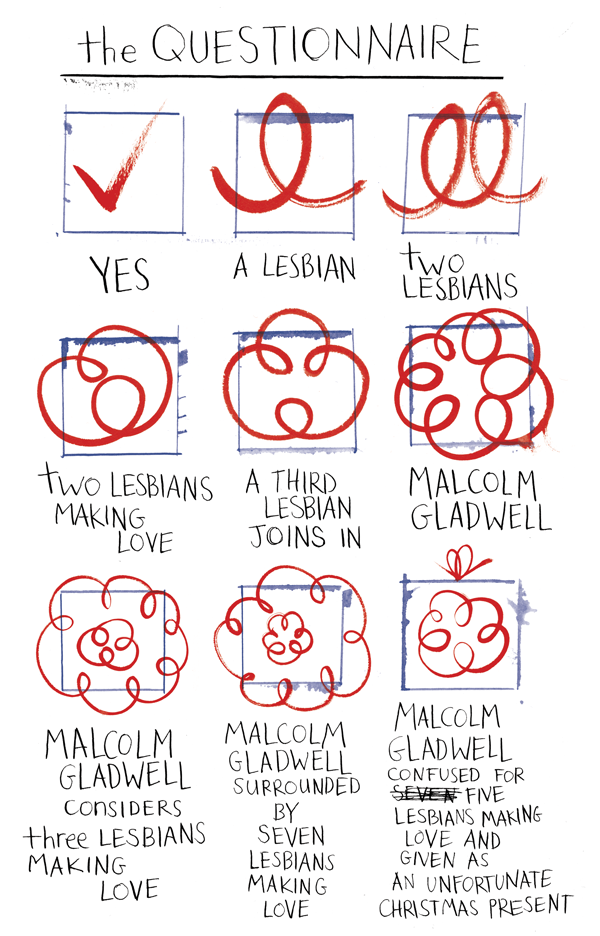

RM: I had a few strips and I wanted to put them together into a zine, so I copied the design from Beardsley’s Yellow Book, since a lot of my work was somewhat decadent (or rather whiny) in tone back then. The first issue is pretty awful, the second is slightly better, around the third one the strips got a bit more interesting and coherent, the fourth one had an overall concept of Only Disconnect (after E.M.Forster in reverse), number five is the latest and it’s all about smalltalk. The next one will be about scale, although I’m not sure what that means. My favorite parts of 5 are the ones that don’t look like comics, illustration, poems or anything really, like the Malcolm Gladwell page. I will probably continue in that format-bending direction in the further Yellow Zines, so that they remain an outlet for semi-unpublishable experiments in a cheap and disposable form.

Biblioklept: A lot of readers will probably recognize your work from the illustrations you’ve done for organs like The New Yorker and The New York Times. What goes into those pieces? How much editorial direction do you get? There’s a really cohesive connection between those illustrations and the work in Yellow Zine and (In a Sense)—as well as the wonderful illustrations for books you share on your site. Your recent illustration for John Cheever’s classic short story “The Five-Forty-Eight” (at The New Yorker), for example, looks like it could be an outtake from Yellow Zine—but it also fits Cheever’s story perfectly…

RM: I always try to smuggle something artsy into my commercial assignments, but the illustrator and the artist are pretty separate in me. I’m completely flexible and if I’m told that the direction is not working, I rethink it without reservation. Illustration has to serve a purpose, while the absence of any purpose is the starting point for my personal work.

I’d never actually heard of Cheever before the assignment, so it was a pleasant discovery. With the somewhat dreamy treatment I tried to avoid the old-timey look that I’m sometimes pigeonholed into and highlight the rhythm and atmosphere of the piece. I feel that a great deal of classics are far more modern than their reputation may suggest.

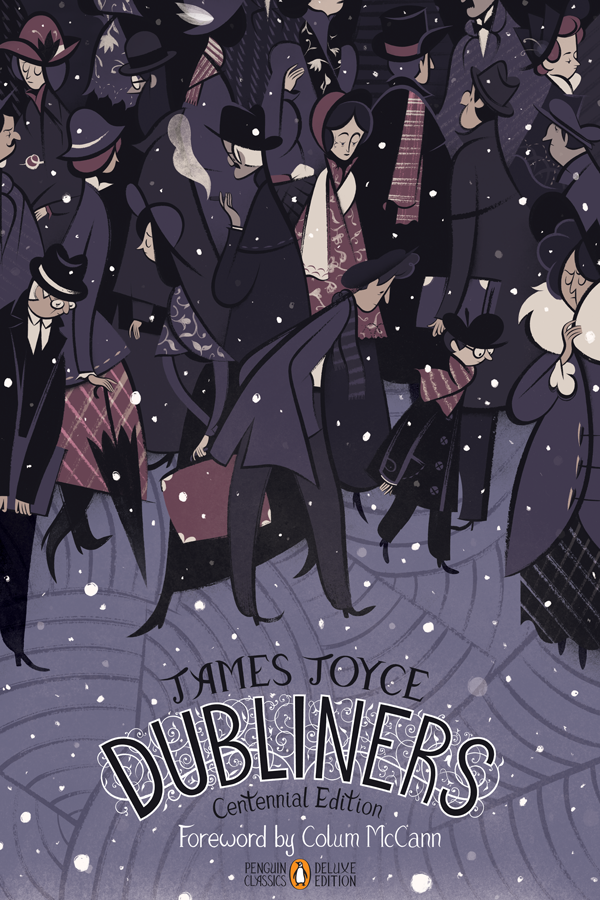

For the Dubliners cover it was a bit of a challenge, since it’s in the Penguin series that has pretty much exclusively cartoonists like Chris Ware, Seth & co. You’re expected to show off your style and have some sort of semi-sequential segments. I tried to make sure none of the characters are too specific, so that the cover is more about their unity in disconnection than about the individual narratives. Then on the back cover I wanted to play with the less obvious connections between the stories and scenes and the flaps provided the perfect vessel for linking the opening of “The Sisters” and the ending of “The Dead,” since they’re on the actual physical ends of the book. My colors were considered too depressing even for Joyce, so the printers upped the brightness for the final jacket.

Biblioklept: You’ve been doing promotion for (In a Sense). Do you think that the “comics community” is more receptive to events like author signings than the “traditional” literary community? What do you do at a book promotion event? You have one coming up in NYC, right?

RM: The comics scene can feel like a support group sometimes–at events and such I very rarely meet anyone who’s not a cartoonist or an aspiring cartoonist. I go to both comics & noncomics signings and I rarely see anyone else doing that. I didn’t see any local cartoonists at a recent Ben Marcus reading for instance, but to be completely honest this sense of not belonging to either side gives me a certain satisfaction.

At my own signings I try to make a fairly elaborate drawing in each copy, so it’s a better deal for the reader–hardcover books are expensive, so having an original drawing in it hopefully makes it a better investment. Also, it’s more fun to come up with a new thing to draw each time.

And yes, I’m doing a signing at a Brooklyn shop called Desert Island with Stephen Collins, who’s promoting his excellent graphic novel The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil. The event is on Friday October 10th from 7 to 9 pm.

Biblioklept: (In a Sense) is a long short story. Do you have a novel in the works? What are you working on next, aside from commercial gigs?

RM: There a couple of longer book ideas I’ve been working on very slowly for the last 2-3 years and they’re both still in early stages (no drawings, no publishers, not even a decent structure). For me it takes a really long time to let an initial idea form into something coherent. One of the stories has been in the back of my mind since 2009 or so, it would be a ~100-page long pseudo-adventure, the other one would be a polyphonic exploration of a single evening. I might scrap all that and make something completely different, so I don’t really want to talk too much about these works-in-progress.

For my own amusement I’m drawing a 40-page story about the illustration industry set in a 1940s New York where twitter is a pneumatic tube and artists steal each other’s work quite literally, through mugging on the street.

There’s also the most boring thing I’ve ever done–a short story in a French anthology Papier which has just one phrase (“Is this art?”) repeated about 40 times. I’m pretty proud of this achievement.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

No, but I’ve managed to read a couple of slim novellas right between the shelves, sometimes over several visits. And we’re really fortunate to have a great library in San Francisco, so I’m never tempted.

This was great! I really, really enjoyed this. I picked up that copy of Dubliners the other day. Seems like I should get hold of his book.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Agree!

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Roman Muradov’s novella (In a Sense) Lost and […]

LikeLiked by 3 people

Reblogged this on and commented:

Interview with Roman Muradov by Edwin Turner

LikeLiked by 3 people

This was excellent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

great post thanks

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very informative and enlightening read.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I loved this piece, so intriguing.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Great Post!

http://ramonacrisstea.wordpress.com

LikeLiked by 3 people

Love his style. Will definitely have to give his graphic novella a read. Thanks for the post!

LikeLiked by 4 people

Reblogged this on ARTE, SIMPLESMENTE….

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Muradov said about the creation of (In A Sense). In an interview with Edwin Turner for the website Biblioklept, Muradov says, “… a great deal of (In A Sense) was inspired by the sudden widespread acceptance […]

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Source: Comics, Kafka, and Satire: Illustrator Roman Muradov […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Empires, Cannibals, and Magic Fish Bones and commented:

A wonderful interview with one of my favorite illustrators. I suggest pairing it with coffee.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on re-writing reality blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Source: Comics, Kafka, and Satire: Illustrator Roman Muradov […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Source: Comics, Kafka, and Satire: Illustrator Roman Muradov […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged,:

mysterious, refined. intense, smart,seroius drawings…a treat!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! I didn’t know anyone else had read At Swim To Birds! An interesting interview with an innovative illustrator, with a nostalgic twist – reminds me of German expressionist illustrators from the twenties and early thirties..

LikeLiked by 2 people

This was very interesting… Thank you very much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on msamba.

LikeLike

Terrific cover for Dubliners. Fits the stories well.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on and commented:

Love this interview

~~~

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb.

LikeLike

[…] Origen: Comics, Kafka, and Satire: Illustrator Roman Muradov […]

LikeLike

Here ist the written Story of “In a sense”: https://web.archive.org/web/20100721130535/http://www.bluebed.net/ongoing/innocence Vive l’archive!

LikeLike