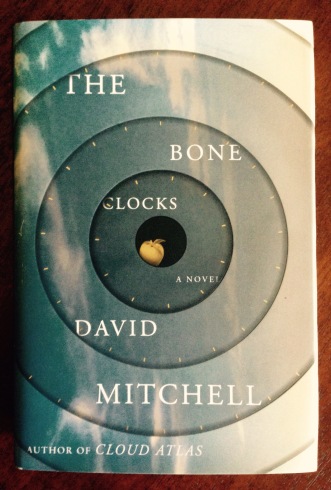

David Mitchell’s latest novel The Bone Clocks is 624 pages in hardback, its sprawling metaphysical plot jammed into six overlapping sections that move through six decades and several genres. Any number of critical placeholders might be applied here: Sweeping, ambitious, genre-skewering, kaleidoscopic (I stole that last one from the book jacket). Or, perhaps we prefer our descriptors more academic? Okay: Postmodern, metatextual, metacritical, polyglossic. With The Bone Clocks, Mitchell has used these functional, formal postmodernist techniques to string together a few good novellas with some not-so-good novellas into a novel that’s not bad—but also not particularly good.The Bone Clocks is just okay. It fills space, it fills time. But unlike Mitchell’s previous stronger novels—Black Swan Green and Cloud Atlas in particular—The Bone Clocks fills without nourishing.

The Bone Clocks opens in 1984 with “A Hot Spell,” introducing us to the novel’s ostensible subject, Holly Sykes, a fifteen year-old who runs away from home. This section also introduces us to Mitchell’s consistent idiom here, a first-person present tense narration that forces the plot forward like an engine. When Mitchell needs to deliver any background information, the narrator simply trots out old memories, or a character politely shows up to dump exposition. The exposition-dumping is particularly egregious in the novel’s final sections.

Our heroine Holly Sykes helps out with some of that exposition early on, filling in some of the contours we’ll need to understand if we want to suss out the Big Metaphysical Plot of The Bone Clocks: There are “the radio people,” voices that contact Holly, um, telepathically; there are the strange figures of Marinus and Constantin; there is the drama of Holly’s deep-souled, old-souled little brother Jacko, who ominously makes her memorize a labyrinthine map in the book’s early pages (foreshadowing!):

The one Jacko’s drawn’s actually dead simple by his standards, made of eight or nine circles inside each other.

“Take it,” he tells me. “It’s diabolical.”

“It doesn’t look all that bad to me.”

“ ‘Diabolical’ means ‘satanic,’ sis.”

“Why’s your maze so satanic, then?”

“The Dusk follows you as you go through it. If it touches you, you cease to exist, so one wrong turn down a dead end, that’s the end of you. That’s why you have to learn the labyrinth by heart.”

Christ, I don’t half have a freaky little brother.

“Right. Well, thanks, Jacko. Look, I’ve got a few things to—” Jacko holds my wrist. “Learn this labyrinth, Holly. Indulge your freaky little brother. Please.” That jolts me a bit.

See how young Holly doesn’t quite cotton that Jacko has, like, responded to her by using the same phrase she thought but didn’t say aloud? Mitchell has a talent for crafting characters like this—characters who can’t see their own blind spots, characters utterly naïve to how we see them. Mitchell excelled at this technique in Black Swan Green, whose narrator Jason Taylor describes for us what he cannot name or fully understand. Holly’s 1984 narrative often feels like a rewrite of Black Swan Green. Jason actually shows up—sort of—in The Bone Clocks; his cousin Hugo Lamb, a minor character in Black Swan Green, narrates the section after young Holly’s story.

Hugo Lamb’s “Myrrh Is Mine, Its Bitter Perfume” propels us to 1991. Lamb is a charming, conniving con man. If young Holly echoes Adam Ewing of Mitchell’s superior novel Cloud Atlas in her naïve innocence (she does), then Hugo Lamb echoes Cloud Atlas’s genius con man, Robert Frobisher. Indeed, most of the central narrators in The Bone Clocks read like familiar repetitions of characters from Cloud Atlas. I enjoyed Frobisher’s plotting and scheming, and I enjoyed it again in Lamb, a sympathetic rake. I was digging The Bone Clocks all through his section, despite feeling vaguely worried that Mitchell was not exactly doing much to flesh out The Big Metaphysical Plot that would have to hold this thing together.

It’s after Lamb’s section (nice cliffhanger!) that The Bone Clocks really begins to stumble. Mitchell jumps to 2004, into the consciousness of war journalist Ed Brubeck (first introduced in Holly’s narrative, as a non-war-journalist teen). Holly’s here in 2004 too—and she was in Lamb’s riff, and all the sections, of course—but she’s a marginal figure, which is fine, I suppose. However, instead of using Brubeck’s narrative to advance The Big Metaphysical Plot (which begins to feel like a MacGuffin at this point), Mitchell indulges in a long rant against Blair and Bush and the Iraq War and etc. Look, I get it: I’ll never forget those years either—I don’t think I’ll ever be able to sustain outrage in the manner in which I did through the Bush years—but the effect is numbing, boring, dull.

Mitchell has a get-out-of-jail-for-free card under his side of the game board, however, in the form of Crispin Hershey, a writer who fears his best days are far behind him. (Crispin’s Cloud Atlas predecessor, if you’re keeping count, is Timothy Cavendish). Set over the next few years of our own future (forgive this clunky dependent clause), “Crispin Hershey’s Lonely Planet” is perhaps the strongest section of The Bone Clocks. We’re treated to/subjected to an extended parody of the so-called literary world, with Hershey standing in for a certain type of White Male Writer in general (and Martin Amis, in particular). The satirical section allows Mitchell to anticipate, enact, and respond to criticisms of The Bone Clocks itself. The opening pages of “Crispin Hershey’s Lonely Planet” give us a critic thrashing Hershey’s latest novel, Echo Must Die (note the not-so-subtle allusion in the title):

So why is Echo Must Die such a decomposing hog? One: Hershey is so bent on avoiding cliché that each sentence is as tortured as an American whistleblower. Two: The fantasy subplot clashes so violently with the book’s State of the World pretensions, I cannot bear to look. Three: What surer sign is there that the creative aquifers are dry than a writer creating a writer-character?”

Yes, the creation and insertion of a writer-character is a meat-and-potatoes postmodern gambit, but I think it works here, even if we might roll our eyes at the metacritical moves—the fantasy subplot does clash against The Bone Clocks’ “State of the World Pretensions”. In fairness though, Mitchell doesn’t seem to worry too much about resting on clichés. (Maybe I should watch out: The rest of the Hershey plot revolves around revenge against the critic!). The Hershey narrative also does a particularly good job of checking in with and updating Holly Sykes, who, in her middle age, has found unlikely success in writing a book called The Radio People.

The Hershey section balances The Big Metaphysical Plot well, slowly teasing out intriguing details. Unfortunately, the next section, “An Horologist’s Labyrinth,” tangles those threads into a messy net of tired YA sci-fi tropes. This is the climax, people!, the penultimate chapter in which The Big Metaphysical Plot reveals itself. There is a psychic war, people!, and here it will reach its Big Final Battle—and of course Holly Sykes is involved, deeply, intimately, labyrinthically. Simultaneously rushed and bloated, “An Horoglogist’s Labyrinth” should be the acme of The Bone Clocks, but it feels like the nadir. The chapter introduces a superhero team of near-immortals who must endlessly battle a supervillain squad (psychic vampires, natch)—only, like that endlessly deal is, like, coming to an end. Mitchell mashes all these new characters (and whatever hopes and motivations they may have had) up against the back-story of the section’s narrator, Marinus, which unspools over a few centuries. Overstuffed with stories and plots and counterplots, “An Horologist’s Labyrinth” relies on exposition dump after exposition dump to move forward. Loose ends tangle into a mess. After slowly simmering The Big Metaphysical Plot for 400 pages, Mitchell turns up the gas, burning through (what should be) key events before the reader can remember to care.

The Bone Clocks concludes by pulling the same post-apocalyptic trick that Mitchell used in the center of Cloud Atlas. We’re back with Holly Sykes now; its 2043 in the south of Ireland, where a little bit of stability remains after the Endarkenment. You know what the Endarkenment is, dear reader, having, I assume, read or seen any number of post-apocalyptic/dystopian narratives. Mitchell offers here a scornful lecture and a dire prognosis, but little else.

If The Bone Clocks is derivative (and what novel isn’t?), it’s mostly derivative of Mitchell’s own novel Cloud Atlas. I was and am a fan of that book, which used its postmodern gimmickry to deliver some really good yarns—and then weave those yarns into a coherent and compelling tapestry, a Big Picture. The Bone Clocks doesn’t achieve that cohesion, nor does it offerany particularly profound analyses of the Big Themes it seeks to address. Unwieldy but not sloppy, often clever and charming, The Bone Clocks is not a bad book—but it’s never more than the sum of its parts, and it’s not exactly clear what those parts add up to.

I see that I’ve committed the sin of using too much plot summary in my review (I will make my excuses and prayers to St. Updike). Perhaps—and perhaps I’m just grasping to excuse my own failures—perhaps I’ve overshared The Bone Clocks’ plot because I could find little else in the novel beyond plot, platitudes, and screeds.

I read The Bone Clocks in tandem with an auditing of the audiobook version produced by Recorded Books (and sent to me by the kind people at Audible). The audiobook is an excellent production, well-directed and well-acted, with six distinct actors (

It’s a shame to hear this. I’ve had my eye on it!

LikeLike

I can’t think of any way one might review The Bone Clocks without going into a lot of plot summary — I’m quite glad you did. I’ve had trouble knowing what sort of customers at my bookshop would like this book. Your review has helped immensely, so thanks!

LikeLike

Steer them away from this one and to any of Mitchell’s other titles. This is his first misfire in an otherwise stellar career.

LikeLike

Second misfire… first being Number 9 Dream. I’d still place this at #4 or 5 out of his novelistic oeuvre.

LikeLike

[…] The Bone Clocks, David Mitchell […]

LikeLike