A. The first time I saw Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Inherent Vice, I was in the middle of rereading Pynchon’s novel The Crying of Lot 49, which I hadn’t read in fifteen years. I remembered the novel’s vibe, its milieu, but not really its details.

B. I read The Crying of Lot 49 and then immediately reread it. It seemed much stronger the second time—not nearly as silly. Darker. Oedipa Maas, precursor to Doc Sportello, trying not to lose the thread as she leaves the tower for the labyrinth, rushing dizzy into the sixties.

C. Another way of saying this: Inherent Vice is sequel to The Crying of Lot 49. Any number of details substantiate this claim (and alternately unravel it, if you wish, but let’s not travel there)—we could focus on the settings, sure, or maybe the cabals lurking in the metaphorical shadows of each narrative—is The Golden Fang another iteration of The Tristero?—but let me focus on the conclusions of both novels and then discuss the conclusion of PTA’s film.

D. A favorite line from a favorite passage from The Crying of Lot 49: “the true paranoid for whom all is organized in spheres joyful or threatening about the central pulse of himself.” Paranoia as a kind of sustained hope, a way to find meaning, order, a center.

E. The final pages of The Crying of Lot 49 find Oedipa trying to make sense of the labyrinth (my emphases in bold):

For it was now like walking among matrices of a great digital computer, the zeroes and ones twinned above, hanging like balanced mobiles right and left, ahead, thick, maybe endless. Behind the hieroglyphic streets there would either be a transcendent meaning, or only the earth. In the songs Miles, Dean, Serge and Leonard sang was either some fraction of the truth’s numinous beauty (as Mucho now believed) or only a power spectrum. Tremaine the Swastika Salesman’s reprieve from holocaust was either an injustice, or the absence of a wind; the bones of the GI’s at the bottom of Lake Inverarity were there either for a reason that mattered to the world, or for skin divers and cigarette smokers. Ones and zeroes. So did the couples arrange themselves. At Vesperhaven House either an accommodation reached, in some kind of dignity, with the Angel of Death, or only death and the daily, tedious preparations for it. Another mode of meaning behind the obvious, or none. Either Oedipa in the orbiting ecstasy of a true paranoia, or a real Tristero. For there either was some Tristero beyond the appearance of the legacy America, or there was just America and if there was just America then it seemed the only way she could continue, and manage to be at all relevant to it, was as an alien, unfurrowed, assumed full circle into some paranoia.

There is either meaning, or there is not meaning.

F. This passage comes after Oedipa drinks a lot of bourbon and decides to drive “on the freeway for a while with her lights out, to see what would happen”—precursor for the final moments of the novel Inherent Vice, where Doc—alone—drives around LA in a fog both literal and metaphorical.

G. Doc is solitary but joins a convoy of other drivers whose lights create a transitory community, ad hoc, meaningful but bound to dissolve.

H. This dissolution is prefigured in a scene just a page or two before. Doc has just met with Sparky, a character from the novel’s ARPANET plot (elided from the film). Sparky: “It’s all data. Ones and zeros. All recoverable. Eternally present.” Doc’s reply—“Groovy”—indicates a soul perhaps more at peace with the undecidable than Oedipa is.

I. Or maybe Doc, six or seven years after Oedipa’s lead, has assumed the alien paranoia necessary to navigate America. Maybe.

J. Paranoia: Paranoia, again, as the means to make the chaotic cohere.

K. The most frequent negative criticism that I’ve heard about Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Inherent Vice: The film is incoherent. (Let Dana Stevens’ review at Slate stand as a representative example).

L. I don’t think that this criticism is particularly strong—the film coheres thematically around paranoia, and can be succinctly summarized in its own terms:

M. No but hey that’s some fuzzy precis there, bro, thou protest–What’s the film about, man?

N. Let’s let the novel answer:

Sauncho was giving a kind of courtroom summary, as if he’d just been handling a case. “…yet there is no avoiding time, the sea of time, the sea of memory and forgetfulness, the years of promise, gone and unrecoverable, of the land almost allowed to claim its better destiny, only to have the claim jumped by evildoers known all too well, and taken instead and held hostage to the future we must live in now forever. May we trust that this blessed ship is bound for some better shore, some undrowned Lemuria, risen and redeemed, where the American fate, mercifully, failed to transpire…”

Land, hope, possibility. The old good vs. evil deal.

O. You said you’d talk about the film’s conclusion, man.

True.

P. Okay, so there are a couple of differences between the conclusions of the novel and the film. PTA makes his film cohere around the Coy narrative—this ends up being Doc’s good deed, his major success. While the same is true in the book, Anderson’s film is more sentimental in its treatment of the Coy/Hope/Amethyst narrative, more affecting—and more hopeful—than Pynchon’s novel.

Q. (Parenthetically: Owen Wilson was great as Coy. Still, I like to imagine a world where frequent PTA collaborator Philip Seymour Hoffman didn’t die of a heroin overdose but lived to play Coy Harlingen, who also didn’t die of a heroin overdose).

R. Another tonal difference between film and novel is PTA’s treatment of the Bigfoot/Doc relationship, which again is perhaps more sentimental in the film—certainly in the final scene between the two, when it becomes clear that, despite what he says, Doc is, in a sense, Bigfoot’s partner. His brother’s keeper.

S. The most significant difference though in the conclusion of the film is its insertion of Shasta into the final scene. Again, there’s a touch here of PTA’s sentimentality (I use the term admiringly, to be clear); of the resolution that, y’know, resolves, that points toward reconciliation, hope, love, forgiveness, gratitude. (This is the ending of Punch-Drunk Love, Magnolia, Boogie Nights, The Master…). Doc has a final partner in Shasta Fay, a warm body to traverse the fog with. But is it all in his head? Just his imagination? Is Shasta Fey Hepworth really there? Am I being paranoid?

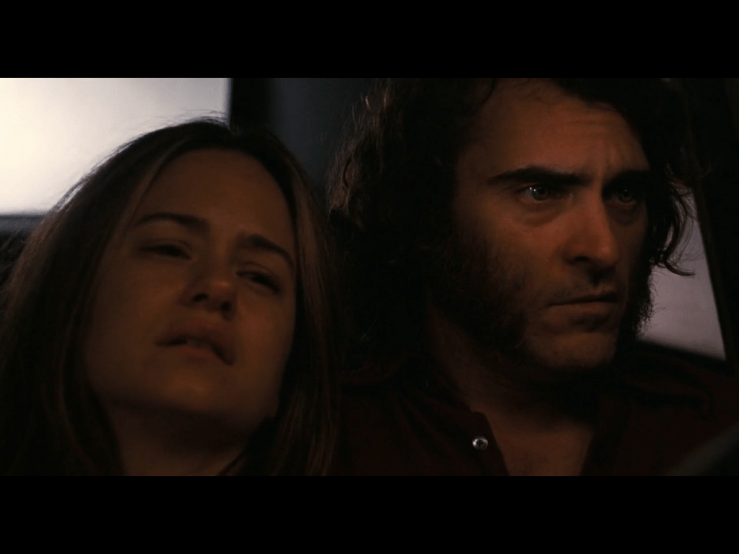

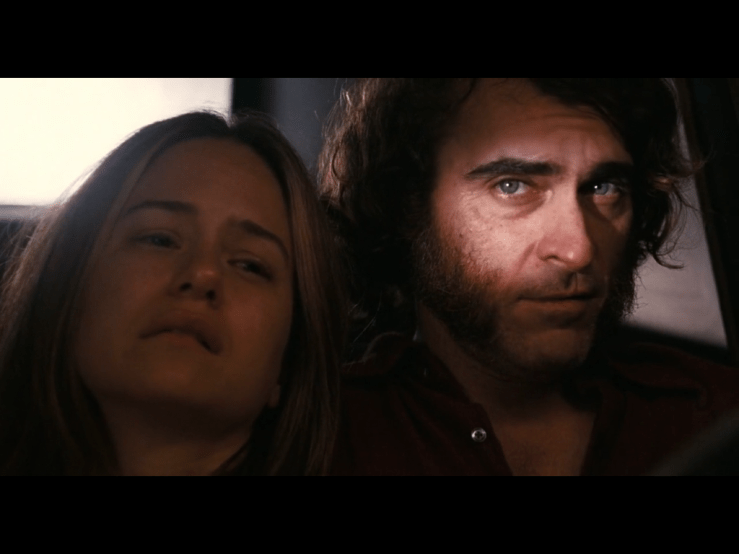

T. The last few seconds of the film are a simple aesthetic marvel. Shasta, the film’s feminine trace, flipping from Flatlander back to hippie chick, from zero to one, lays in a languid haze against Doc’s shoulder, the car encased in night noir fog. Doc seems steady yet unnerved, stolidly paranoid. In the last few seconds, an intense light shines on his face, seems to break through Johnny Greenwood’s woozy dark ominous score.

U. What does Doc see?

His expression: The edge of a smirk? Is there a moment of insight here?

V. And then Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now” comes crashing into the audio with a martial pep that contrasts Greenwood’s somber score and the visual cut to black. The tune’s intro keyboard riff moves from a zany romp to a minor key depression in the span of a few seconds, and Johnson plaintively sings: “Any day now / I will hear you say, ‘Goodbye, my love’ /And you’ll be on your way /Then my wild beautiful bird, you will have flown, oh / Any day now I’ll be all alone.” Is this what Doc sees? That Shasta will fly?

W. So I suppose Inherent Vice is a film about looking: Looking into, over, about; looking under:

X. I wrote this riff for myself. I wrote it in the hope of pinning down the conjunctions and disjunctions between these narratives that have been rattling around in my silly skull. But all it’s done is made me more confused.

Like you, I believe PTA’s film hinges upon Doc’s relationship with Coy, Bigfoot and Shasta.

PTA ramps up the romantic side to Doc, and that pivotal scene when Shasta returns, if you remember, in the novel, it’s split in two: First Shasta appears, they talk, but he’s on the phone with Bigfoot (as in the movie), but it’s only much later that Doc goes to see Shasta and she has that whole speech. The scene in the film is electrifying, much, much more interesting than it is in the film. PTA is definitely highlighting something here… the speech is about how Mickey was much more “masculine” than Doc. Bigfoot comments on Doc’s lack of masculinity as well (when Doc gives him the Wyatt Earp mug). This is of course a big theme for PTA (see, well, all of his movies). The scene with Shasta stops the movie on its tracks (in a good way), so I think it’s worth paying attention to what PTA might be trying to say.

We learn during that phone conversation when Bigfoot’s wife talks to Doc that Doc is the cause for many of Bigfoot’s hangups (psychiatrist’s bills and all). Bigfoot is fascinated by Doc and what he represents. No wonder he gobbles up all of Doc’s pot–Bigfoot’s a very oral man, with the frozen bananas and the pancakes–as if it’s the pot which is the secret to Doc and the hippies, the life he doesn’t understand and never will.

Coy is what Doc could’ve become, the hippie who sells out and loses sight of reality. No wonder that in the book he’s so invisible. Shasta’s on that same boat, with her fixation for Mickey, ran the risk of becoming invisible herself. PTA brings her back to give Doc a sort of (hopeful) happy ending, almost turning Inherent Vice into a comedy of remarriage. It’s curious that in the script (available online), PTA puts a shot of the cars in the fog, not present in the film, and closes the film with Sortilege’s voiceover of the final lines of the book, which he also took out. Leaving things much more mysterious, I think–it’s not even entirely clear they’re going through the fog at that point, and certainly there’s no mention of a convoy of cars to which Doc adheres.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your analysis, Pedro—thanks.

I should have linked to the script, which I referenced a number of times:

Click to access iv.pdf

The Shasta/Doc sex scene in the film is much darker and weirder than (what I imagined in the book)—as you say, it sort of stops the film. And yeah, that’s kind of the last we see of her in the book—in fact, she’s “with” Coy in the narrative (of course it’s in the past) after that in the novel.

But that last scene—it’s almost like a dream scene, a dream fugue, and the light is…I don’t know…time to wake up?

LikeLike

[…] Biblioklept had me thinking that this book was going to be as dense a read as The Crying of Lot 49, so I went slow in on it at first. But slowly I realized that (a) it’s mostly dialogue and narration, and (b) the movie is fairly faithful to the book. Which creates a No Country For Old Men situation for me (or a “February in Baltimore winter-weather-wise” situation). Which means I’m going to really fucking enjoy this thing. And did I really need to say “fucking” just now? Was that really even necessary? […]

LikeLike

[…] “Paranoia as a kind of sustained hope” at Biblioklept […]

LikeLike

[…] True Detective season 2’s superior cousin, Paul Thomas Anderson’s film adaptation of Inherent Vice. There are plenty of plot convergences between these two, but the tonal overlap is more interesting […]

LikeLike

[…] The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon* […]

LikeLike

[…] know, Inherent Vice was released in late 2014 too, but I saw it and loved it and obsessed over it in […]

LikeLike

[…] is that many readers’ first experiences reading Pynchon may have been like mine: I read The Crying of Lot 49 as a college assignment, found it bewildering and baffling, and despite understanding almost none […]

LikeLike

[…] is that many readers’ first experiences reading Pynchon may have been like mine: I read The Crying of Lot 49 as a college assignment, found it bewildering and baffling, and despite understanding almost none […]

LikeLike

“For there either was some Tristero beyond the appearance of the legacy America, or there was just America and if there was just America then it seemed the only way she could continue, and manage to be at all relevant to it, was as an alien, unfurrowed, assumed full circle into some paranoia.”

“Delirium literally means going out of a furrow you’ve been plowing. Think of this as a productive sort of delirium.” Drave to Lew Basnight.

LikeLike