Yuri Herrera’s sharp, thrilling novella Signs Preceding the End of the World opens with calamity. A sinkhole — “the earth’s insanity” — nearly swallows our hero before we can properly meet her:

I’m dead, Makina said to herself when everything lurched: a man with a cane was crossing the street, a dull groan suddenly surged through the asphalt, the man stood still as if waiting for someone to repeat the question and then the earth opened up beneath his feet: it swallowed the man, and with him a car and a dog, all the oxygen around and even the screams of passers-by. I’m dead, Makina said to herself, and hardly had she said it than her whole body began to contest that verdict and she flailed her feet frantically backward, each step mere inches from the sinkhole, until the precipice settled into a perfect circle and Makina was saved.

This opening passage sets the tone of Signs Preceding the End of the World. Makina will repeatedly plunge into and out of danger as she treks from her village in borderland Mexico into the weird world of the Big Chilango–the United States.

Makina crosses the border to find her estranged brother, who left the village years ago with the dubious plan of claiming some land (supposedly) owned by his family. (Reader, mark the symbolism there). Makina’s mother prompts her journey, but she’s also aided by a trio of adversarial gangsters—Mr. Double-U, Mr. Aitch, and Mr. Q. At the end of the first chapter of Signs, Mr. Q summarizes Makina’s impending quest (and the novella itself) in terse but eloquent language:

You’re going to cross and you’re going to get your feet wet and you’re going to be up against real roughnecks; you’ll get desperate, of course, but you’ll see wonders and in the end you’ll find your brother, and even if you’re sad, you’ll wind up where you need to be.

Mr. Q plays seer in his short monologue, just one example of the novella’s mythic overtones. Or maybe the word I want is undertones: Signs Preceding the End of the World opens with the earth swallowing victims; underworld mobsters send a hero on a night-quest over rough waters and alien terrain; aided by an underground network, Makina must traverse labyrinths and mazes and dark spaces; and, yes, the book ends underground. This is subterranean fiction.

The mythic dimensions of Signs work so well precisely because of the novella’s concrete contours. Herrera’s prose (in Lisa Dillman’s marvelous English translation) is somehow simultaneously compact but expansive, each detail vital. (Reading Signs Preceding the End of the World, I finally understood what might be meant by that critical placeholder “muscular prose” — there is no fat here, but the book is in no way thin). Take for example an early passage wherein Herrera establishes Makina’s grit. As she boards a bus headed north, Makina faces ogling and harassment by two men — “hardly more than kids, with their peach fuzz and journey pride.” One sits next to her, uninvited, emitting bad intentions:

Makina felt the first contact, real quick, as if by accident, but she knew that type of accident: the millimetric graze of her elbow prefaced ravenous manhandling. She sharpened her peripheral vision and prepared for what must come , if the idiot did persist. He did.

After the boy brushes Makina’s thigh, she breaks his finger:

Makina turned to him, stared into his eyes so he’d know that her next move was no accident, pressed a finger to her lips, shhhh, eh, and the other hand yanked the middle finger of the hand he’d touched her with almost all the way back to an inch from the top of his wrist; it took her one second. The adventurer fell to his knees in pain…

(The notation of the “adventurer” strikes me as both funnier and crueler as I read it again now to type this out).

Signs is full of exhilarating moments, sharp, economic turns, both at plot and sentence level. To use its own term, the book “verses,” moves, exits, shifts. Verse is Dillman’s smart translation of Herrera’s own neologism jarchar. Dillman writes in her translator’s note that jarchar derives from “jarchas (from the Arabic kharja, meaning exit), which were short Mozarabic verses or couplets tacked on to the end of longer Arabic or Hebrew poems written in Al-Andulus, the region we now call Spain.” Note here, dear reader, the synthesis, the shifts, the hybridization, the semiotic openness of Dillman’s verse. The word encapsulates not just the book’s rhythm and tone, but also its spirit of transmission, transmogrification, and change.

For all its versing and speed though, Herrera’s novella is often contemplative (and poetic), as when Makina observes “the anglogaggle at the self-checkouts…how miserable they looked in front of those little digital screens.” Or when an old Mexican (who says he’s “just passing through,” despite having lived in the U.S. for fifty years), explains Americas’s favorite pastime to Makina, who’s stunned by the architecture of a baseball stadium:

Every week the anglos play a game to celebrate who they are. … One of them whacks it, then sets off like it was a trip around the world, to every one of the bases out there, you know the anglos have bases all over the world, right? Well the one who whacked it runs from one to the next while the others keep taking swings to distract their enemies, and if he doesn’t get caught he makes it home and his people welcome him with open arms and cheering.

The passage condenses realism and mythology, and shows how that very condensation underwrites so much of our own understanding (or misunderstanding) of U.S. America. The book’s mythic aesthetic is not an anesthetic to dull the cultural-political-economic realities of the borderland; rather, Makina’s quest taps into the deeper roots of story-telling and sharpens the stakes for character and reader alike. The mythic subterranean is real: In the labyrinth under the surface, tunnels disregard borders.

Makina, navigating that labyrinth, sees a future, hears it in the speech of the “homegrown” transplants making a new life in the U.S.:

They speak an intermediary tongue that Makina instantly warms to because it’s like her: malleable, erasable, permeable; a hinge pivoting between two like but distant souls, and then two more, and then two more, never exactly the same ones; something that serves as a link.

Makina finds in the language “a nebulous territory between what is dying out and what is not yet born. But not a hecatomb… not a sudden absence but a shrewd metamorphosis.” For Makina,

It’s not another way of saying things: these are new things. The world happening anew, Makina realizes: promising other things, signifying other things, producing different objects.

Language here promises a future of new things and a new we. Later, a character remarks of the anglos: “They want to live forever but still can’t see that for that to work they need to change color and number. But it’s already happening.” As Signs shuttles to its thrilling conclusion, Herrera engages the costs and payoffs of that change.

Personal and expansive, dense but compact, Signs Preceding the End of the World offers its readers a timeless and timely epic in miniature. Highly recommended.

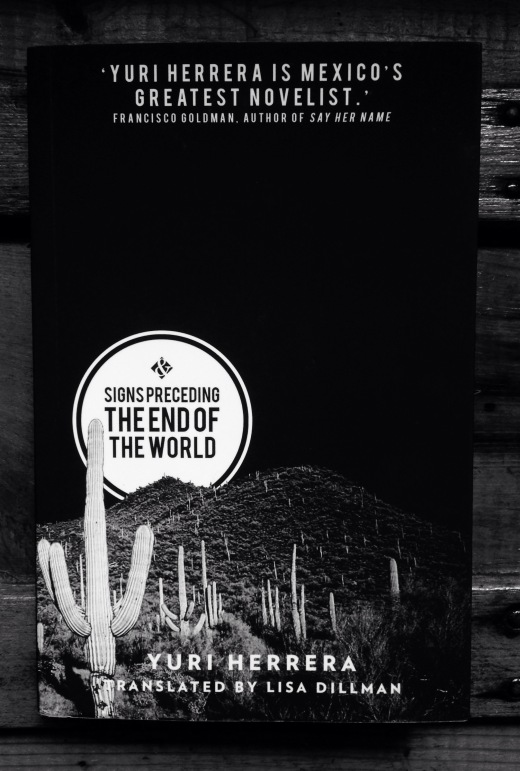

Signs Preceding the End of the World is new in paperback and ebook from And Other Stories.

Wow. I might have to go buy this book now. Thanks for reviewing it!

LikeLike

This is one of those books you want to stand on street corners and hand out to strangers. Timely epic in miniature indeed. Great review!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on world's life.

LikeLike

[…] Signs Preceding the End of the World, Yuri Herrera […]

LikeLike

[…] Signs Preceding the End of the World, Yuri Herrera […]

LikeLike

[…] in one sitting a few months back, and I owe it a proper review. Herrera’s previous novella, Signs Preceding the End of the World, was one of my favorite books published last […]

LikeLike

[…] Cons as the third part of a loose trilogy that also includes Herrera’s previous novellas Signs Preceding the End of the World and The Transmigration of Bodies. All three are published by And Other Stories and all three are […]

LikeLike

[…] Here is an example of a book review of his. He combines snippets of the text with context and plot that offers a good introduction to a book. I find it quite helpful when deciding if this is something I would be interested in reading […]

LikeLike

I love this book and this is such a good review.

LikeLike