Beyond the fact that audiobooks allow me to experience more books than I would be able to otherwise, I like the medium itself: I like a reader reading me a story. Like a lot of people, some of my earliest, best memories are of someone reading to me. (The narrative in my family was always that my mother fell asleep while reading me The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and that I picked it up and finished it on my own and that’s how I “learned” to read—I’m not really sure of this tale’s veracity, which makes it a good story, of course). So I’ve never fully understood folks who sniff their noses at audiobooks as less than real reading.

Indeed, the best literature is best read aloud. It is for the ear, as William H. Gass puts it in his marvelous essay “The Sentence Seeks Its Form”:

Breath (pneuma) has always been seen as a sign of life . . . Language is speech before it is anything. It is born of babble and shaped by imitating other sounds. It therefore must be listened to while it is being written. So the next time someone asks you that stupid question, “Who is your audience?” or “Whom do you write for?” you can answer, “The ear.” I don’t just read Henry James; I hear him. . . . The writer must be a musician—accordingly. Look at what you’ve written, but later … at your leisure. First—listen. Listen to Joyce, to Woolf, to Faulkner, to Melville.

Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner, Melville—a difficult foursome, no? I would argue that the finest audiobooks—those with the most perceptive performers (often guided by a great director and/or producer) can guide an auditor’s ear from sound to sense to spirit. A great audiobook can channel the pneuma of a complex and so-called difficult novel by animating it, channeling its life force. The very best audiobooks can teach their auditors how to read the novels—how to hear and feel their spirit.

I shall follow (with one slight deviation, substituting one William for another) Gass’s foursome by way of example. Joyce initiates his list, so:

I had read Joyce’s Ulysses twice before I first experience RTÉ’s 1982 dramatized, soundtracked, sound-effected, full cast recording of the novel (download it via that link). I wrote about the Irish broadcast company’s production at length when I first heard it, but briefly: This is a full cast of voices bringing the bustle and energy (and torpor and solemnity and ecstasy and etc.) of Bloomsday to vivid vivacious vivifying life. It’s not just that RTÉ’s cast captures the tone of Ulysses—all its brains and hearts, its howls and its harrumphs—it’s also that this production masterfully expresses the pace and the rhythm of Ulysses. Readers (unnecessarily) daunted by Ulysses’s reputation should consider reading the book in tandem with RTÉ’s production.

Woolf is next on Gass’s list. Orlando is my favorite book of hers, although I have been told by scholars and others that it is not as serious or important as To the Lighthouse or Mrs. Dalloway. It is probably not as “difficult” either; nevertheless, put it on the list! Clare Higgins’s reading of Orlando remains one of my favorite audiobooks of all times: arch without being glib, Higgins animates the novel with a picaresque force that subtly highlights the novel’s wonderful absurdities.

Faulkner…well, did you recall that I admitted I would not keep complete faith to Gass’s short list? Certainly Faulkner’s long twisted sentences evoke their own mossy music, but alas, I’ve yet to find an audiobook with a reader whose take on Faulkner I could tolerate. I tried Grover Gardner’s take on Absalom, Absalom! but alas!—our reader often took pains to untangle what was properly tangled. I don’t know. I was similarly disappointed in an audiobook of The Sound and the Fury (I don’t recall the reader). And yet I’m sure Faulkner could be translated into a marvelous audiobook (Apprise me, apprise me!).

Let me substitute another difficult William: Gaddis. I don’t know if I could’ve cracked J R if I hadn’t first read it in tandem with Nick Sullivan’s audiobook. J R is a tragicomic opera of voices—unattributed voices!—and it would be easy to quickly lose heart without signposts to guide you. Sullivan’s reading is frankly amazing, a baroque, wild, hilarious, and ultimately quite moving performance of what may be the most important American novel of the late twentieth century. A recent reread of J R was almost breezy; Sullivan had taught me how to read it.

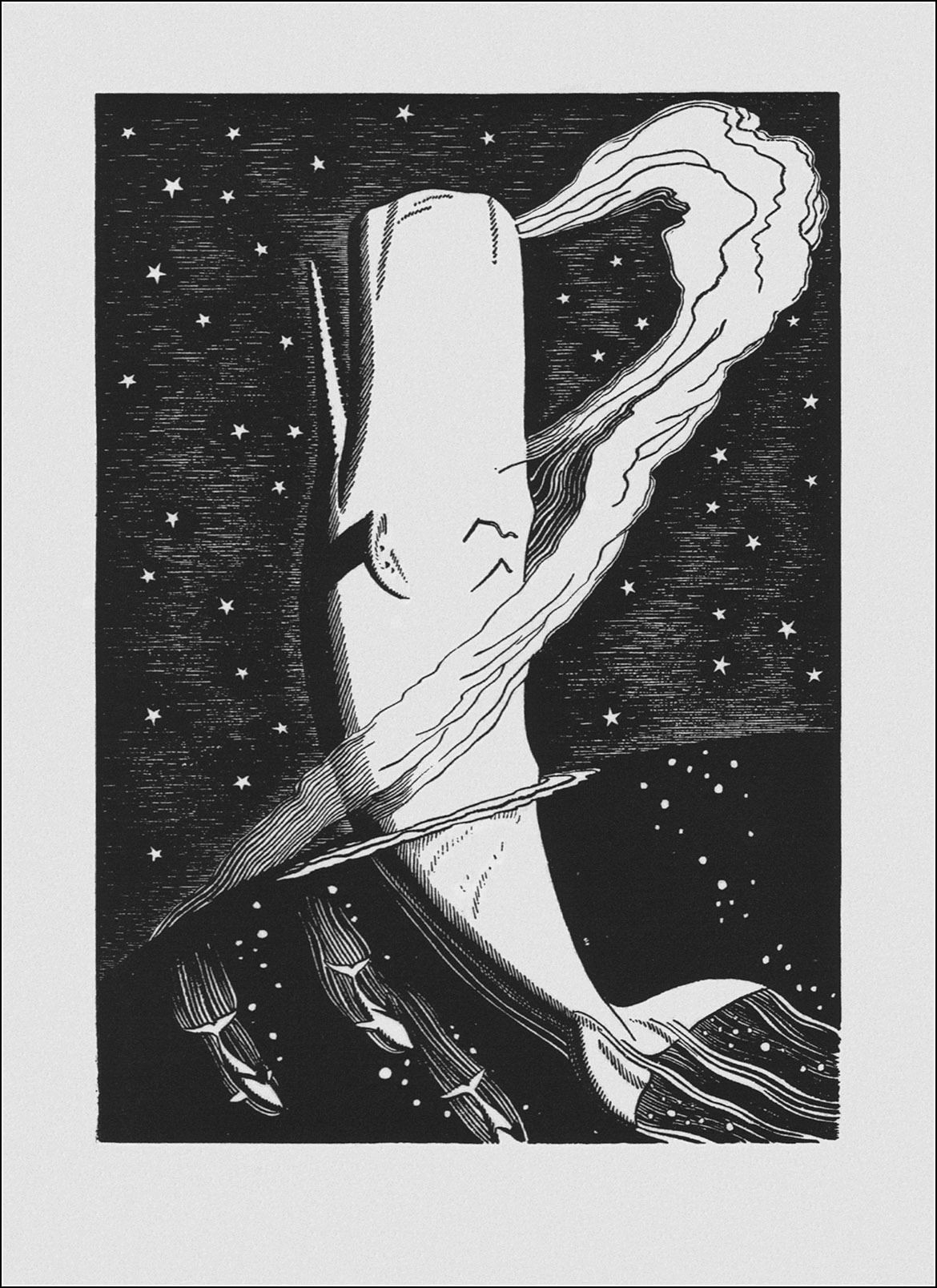

Mighty Melville caps Gass’s list. I had read Moby-Dick a number of times, studying it under at least two excellent teachers, before I first heard William Hootkins read it. (Hootkins, a character actor, is probably most well-known as the X-wing pilot Porkins in A New Hope). As a younger reader, I struggled with Moby-Dick, even as it intrigued me. I did not, however, understand just how funny it was, and even though I intuited its humor later in life, I didn’t fully experience it until Hootkins’ reading. Hootkins inhabits Ishmael with a dynamic, goodwilled aplomb, but where his reading really excels is in handling the novel’s narrative macroscopic shifts, as Ishmael’s ego seems to fold into the crew/chorus, and dark Ahab takes over at times. But not just Ahab—Hootkins embodies Starbuck, Flask, and Stubb with humor and pathos. Hootkins breaths spirit into Melville’s music. I cannot overstate how much I recommend Hootkins audiobook, particularly for readers new to Moby-Dick. And readers old to Moby-Dick too.

“What can we do to find out how writing is written? Why, we listen to writers who have written well,” advises (or scolds, if you like) William Gass. The best audiobook performances of difficult books don’t merely provide shortcuts to understanding those books—rather, they teach auditors how to hear them, how to feel them, how to read them.

Great advice. The best writing SOUNDS great, with the rhythm of the words a grand testament to the quality of the classics.

LikeLike

Are you familiar with this reading of Mony Dick? Some readers are better than others, but I enjoyed the variety of voices and interpretations.

http://www.mobydickbigread.com

LikeLike

[…] talks about listening to audio books of difficult novels, and finding their […]

LikeLike

[…] I wrote a post about listening to audiobook versions of “difficult novels,” taking my lead and license from this big quote from William H. Gass’s essay “The Sentence Seeks Its Form”: […]

LikeLike