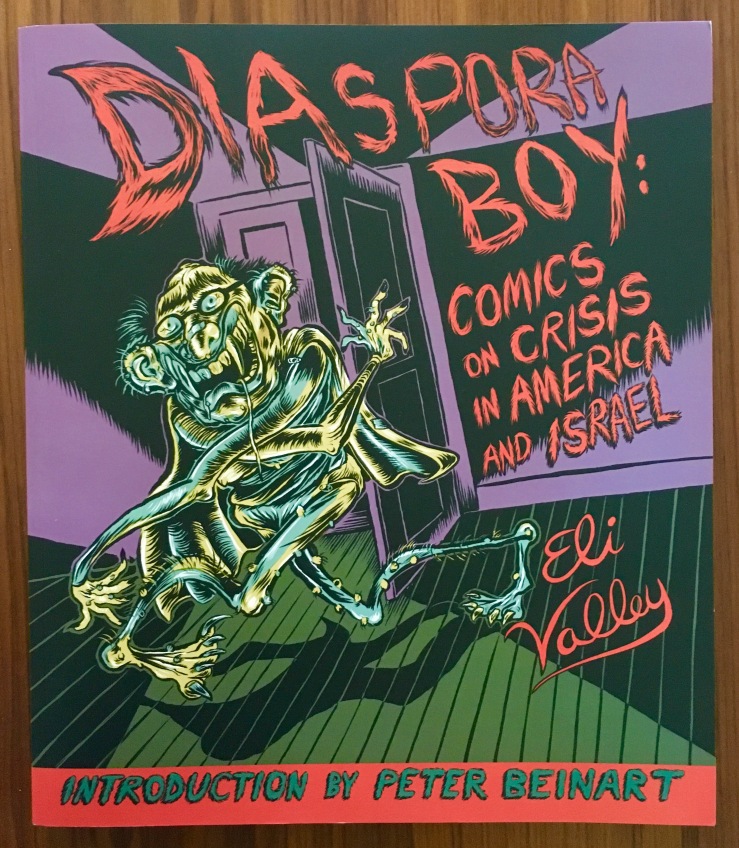

Diaspora Boy, new from O/R Books, collects Eli Valley’s comix from the past decade.

Here’s O/R’s blurb:

Eli Valley’s comic strips are intricate fever dreams employing noir, horror, slapstick and science fiction to expose the outlandish hypocrisies at play in the American/Israeli relationship. Sometimes banned, often controversial and always hilarious, Valley’s work has helped to energize a generation exasperated by American complicity in an Israeli occupation now entering its fiftieth year.

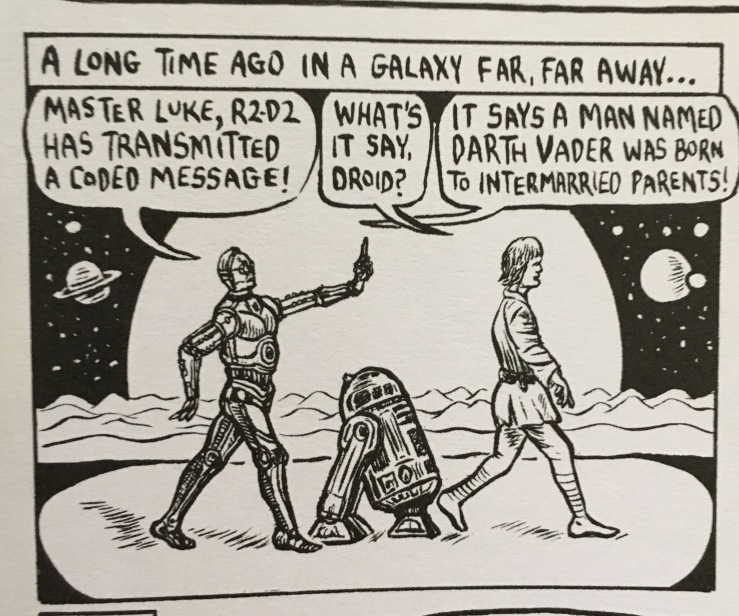

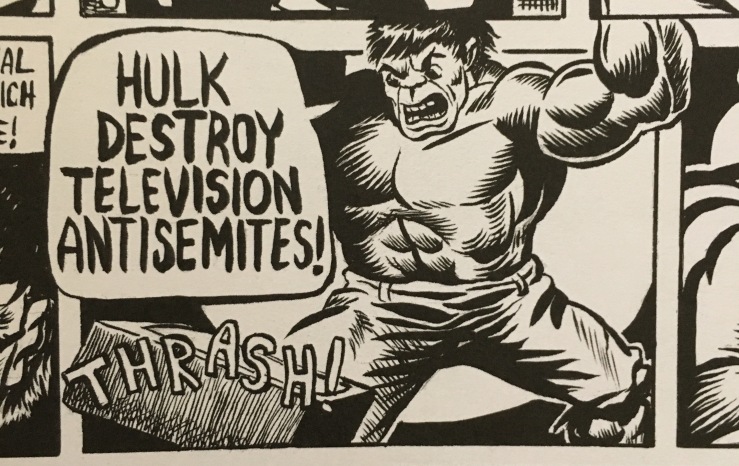

This, the first full-scale anthology of Valley’s art, provides an essential retrospective of America and Israel at a turning point. With meticulously detailed line work and a richly satirical palette peppered with perseverating turtles, xenophobic Jedi knights, sputtering superheroes, mutating golems and zombie billionaires, Valley’s comics unmask the hypocrisy and horror behind the headlines. This collection supplements the satires with historical background and contexts, insights into the creative process, selected reactions to the works, and behind-the-scenes tales of tensions over what was permissible for publication.

Brutally riotous and irreverent, the comics in this volume are a vital contribution to a centuries-old tradition of graphic protest and polemics.

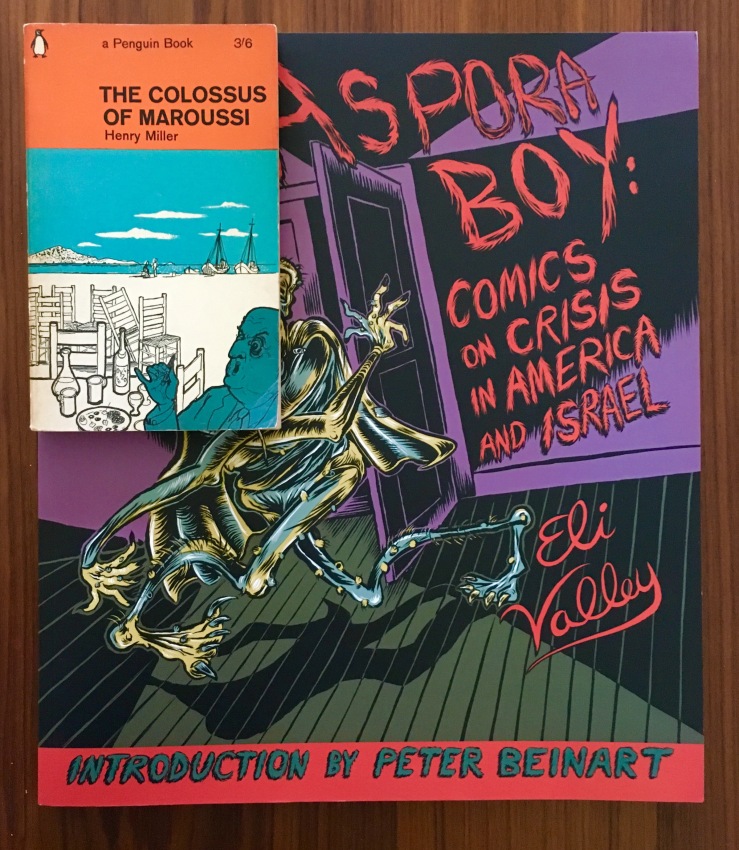

Diaspora Boy, subtitled Comics on Crisis in America and Israel, is enormous (if a slim 144 pages). Valley’s comix are reproduced on full pages; his thick inks and worried lines are never cramped here—and neither are his words. Here’s a shot of the book with a Penguin novel as a comparison point:

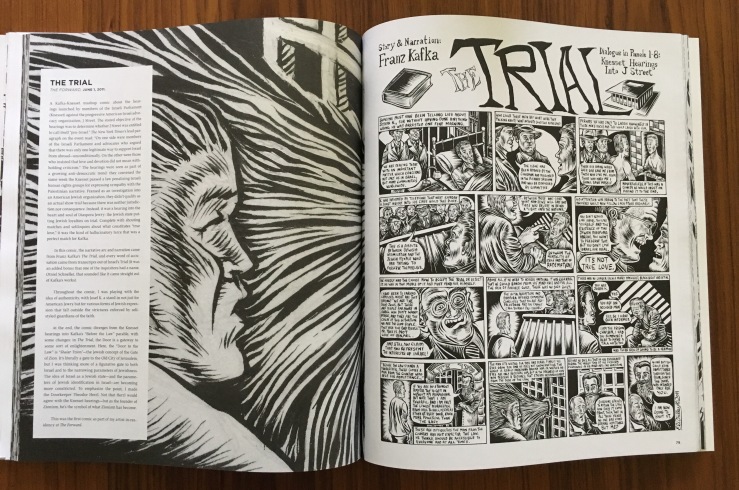

The anthology makes great use of its oversized format. On the left-hand pages, Valley introduces each comic (all chronologically-ordered, by the way) with a short essay that offers context, personal reflections, and even analysis or interpretation. The comics are then reproduced on the right-hand pages. You can see this below, in Valley’s mash-up of Kafka’s The Trial with the Knesset vs. J Street hearings:

The cultural, political—and personal—contexts that Valley provides are perhaps essential for many readers, like me, who may know a bit about comix and Kafka, but are perhaps lost when it comes to a discussion of a “hearing into the heart and soul of Diaspora Jewry” (as Valley puts it).

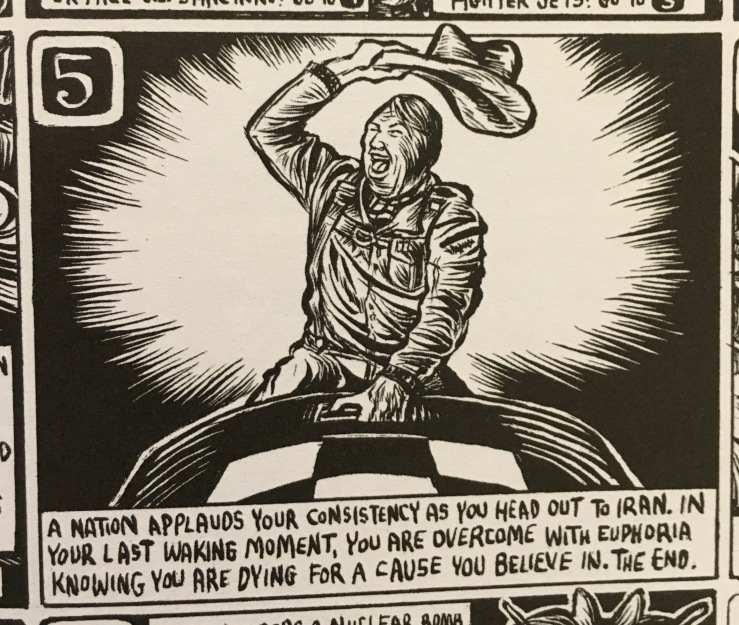

Valley is constantly riffing on American popular culture, mining comic books, films, television and music for his bitter mash-ups, as in “Choose Your Own Apocalypse” below, a comic that turns the Iran debate into a grotesque and ironic Choose Your Adventure tale:

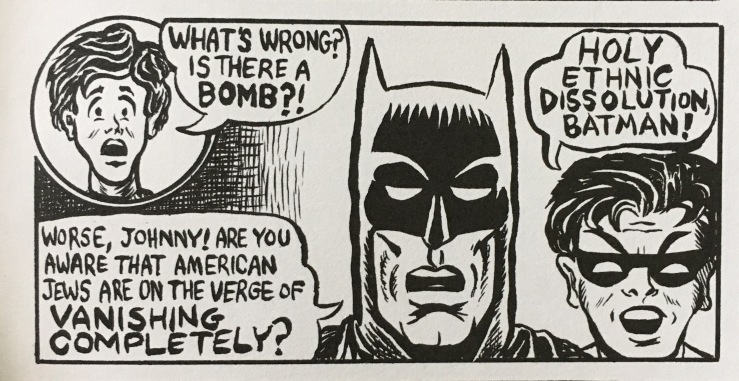

Like many comix artists, Valley’s target audience is nebulous—or rather maybe it’s just himself. He appropriates American culture’s broad shared mythic signifiers to satirize the incredibly specific details of an American Jew’s relationship to Israel—namely, his relationship. The first comic in the collection, 2007’s “What if Batman and Robin Worked in the American Jewish Community?” satirically captures Valley’s teenage anxieties about his relationship to Jewish identity:

In his thorough (and completely necessary) introduction to Diaspora Boy, Valley recounts at some length a complicated relationship with his parents, both Ba’alei Teshurva (he points out that this Hebrew expression “literally means ‘Masters of Return,'” but continues then characterizes it as “a fancy way of of saying ‘Born Again Jews'”). Valley writes that his father interrogated him daily as to whether or not his new friends and acquaintances in his public high school were Jewish or not, and it’s hard not to read these personal anxieties into Valley’s comix (even if I know it’s not good criticism to extrapolate that Valley is “Johnny” in the Batman riff above). Valley’s mother later left the orthodoxy and the marriage, becoming “secular.” Valley positions them, perhaps, as two poles of “reverence and rebellion” which inform his work.

The “reverence” might be hard to spot. In their press page for Diaspora Boy, after three quotes praising Valley’s comix, O/R includes some scathing gems: from former New Republic publisher Marty Peretz: “Your work is disgusting. And also stupid”; Abraham Foxman, former National Director of the Anti-Defamation League: “Bigoted, unfunny”; neocon hack Bret Stephens: “Grotesque…Wretched.” It’s plain to see how conservatives like these might be offended by Valley’s comix. Indeed, it’s not just the message, but the form that they might object to—Valley’s style is sharp but rough, its subtlety relying almost wholly on an extremely ironic viewpoint.

If it’s easy to see how conservatives might resent Valley’s satire, it’s also possible to see how moderates or liberals might misunderstand these comix too. Cartooning has always been a form with an inherently broad appeal. Editorial cartoons are meant to telegraph their ideas quickly and coherently, message and medium intertwined. Valley’s cartoons are harder to suss out. The layering of meaning is intense, magnified. Comic book heroes become displaced into ironic inversions of themselves, consumed by self-hatred. Literary tropes are twisted into a complex entanglement of Jewish-American cultural relations. Biblical stories are transposed into hallucinatory modern horror stories. And in turn contemporary figures—political, economic, cultural, etc.—are subsumed into the same mythic tropes that superheros operate within. It can all be a bit perplexing, and readers who only glance over the surface will miss the real message.

Thus, Valley’s introduction to the volume and his prefaces to each comic become essential context to understanding how to read these comix. The need for political context is especially strong when a cartoon has lost some of its currency due, simply, to the passing of time (they were editorials, after all). However, even when Valley is satirizing a particular news story or political moment that we might have forgotten, a viewpoint comes through, coherent and biting but sincere under all the ironic mechanisms in play. I’ll give Valley the last word here, letting him characterize his own project:

The comics in this collection take pride in Diaspora. Not just in a general sense but in a specific strain of Diaspora experience: the secular, post-Enlightenment, universalist Judaism informed by centuries of Jewish narrative tradition as well as by the experience of living in and amongst other communities. Among other things, it transformed memories of inequality into a lasting cultural norm of solidarity with the oppressed. Theses comics celebrate, relish, and dialogue with that history, a strain of Diaspora that finds far more inspiration in early and mid-twentieth-century social justice movements than in anything wrought in the contemporary Middle East. That is Jewish Pride: pride in the Jewish tradition practiced, experienced, and cherished by the vast majority of American Jews today. And for me, it’s personal. If I’d been brought up solely in the strain of secularism and social justice, I probably wouldn’t have come to filter political passions through an emphatically Jewish lens.

[…] Read here. […]

LikeLike

Well, shit—now I have to buy this, and it looks *expensive*.

LikeLike

It’s like $25 from their website, which I don’t think is too bad for the size and print quality.

LikeLike

If only I lived in America, dear author. $25 doesn’t sound too bad—hopefully somebody will be selling it within the UK at a not-too-painful markup. Sincerely though, thanks for continuing to bring this kind of thing to my attention.

LikeLike