I don’t remember how old I was the first time I saw Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, 1982), but I do remember that it had an instant and formative aesthetic impact on me. Blade Runner’s dark atmosphere and noir rhythms were cut from a different cloth than the Star Wars and Spielberg films that were the VHS diet of my 1980’s boyhood. Blade Runner was an utterly perplexing film, a film that I longed to see again and again (we didn’t have it on tape), akin to Dune (dir. David Lynch, 1984), or The Thing (dir. John Carpenter, 1982)—dark, weird sci-fi visions that pushed their own archetypes through plot structures that my young brain couldn’t quite comprehend.

By the time Scott released his director’s cut of the film in 1993, I’d read Philip K. Dick’s source novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and enough other dystopian fictions to understand the contours and content of Blade Runner in a way previously unavailable to me. And yet if the formal elements and philosophical themes of Blade Runner cohered for me, the central ambiguities, deferrals of meaning, and downright strangeness remained. I’d go on to watch Blade Runner dozens of times, even catching it on the big screen a few times, and riffing on it in pretty much every single film course I took in college. And while scenes and set-pieces remained imprinted in my brain, I still didn’t understand the film. Blade Runner is, after all, a film about not knowing.

Like its predecessor, Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2017) is also a film about not knowing. Moody, atmospheric, and existentialist, the core questions it pokes at are central to the Philip K. Dick source material from which it originated: What is consciousness? Can consciousness know itself to be real? What does it mean to have–or not have—a soul?

Set three decades after the original, Blade Runner 2049 centers on KD6-3.7 (Ryan Gosling in Drive mode). K is a model Nexus-9, part of a new line of replicants created by Niander Wallace and his nefarious Wallace Corporation (Jared Leto, who chews up scenery with tacky aplomb). K is a blade runner, working for the LAPD to hunt down his own kind. At the outset of the film, K doesn’t recognize the earlier model Nexuses (Nexi?) he “retires” as his “own kind,” but it’s clear that the human inhabitants of BR ’49’s world revile all “skinjobs” as the same: scum, other, less human than human. K, beholden to his human masters, exterminates earlier-model replicants in order to keep the civil order that the corporate police state demands. This government relies on replicant slave labor, both off-world—where the wealthiest classes have escaped to—and back here on earth, which is recovering from a massive ecological collapse. The recovery is due entirely to Niander Wallace’s innovations in synthetic farming—and his reintroduction of the previously prohibited replicants.

Our boy K “retires” a Nexus-8 at the beginning of the film. This event leads to the film’s first clue: a box buried under a dead tree. This (Pandora’s) box is an ossuary, the coffin for a (ta da!) female replicant (a Nexus-7 if you’re counting). Skip the next paragraph if you don’t want any plot spoilers.

Forensic analysis of the bones reveals that the replicant died in childbirth. This detail is like, obviously huge, because replicants aren’t supposed to be able to reproduce by themselves. They are made, not born, as BR ’49 repeatedly states in lines cribbed from e.e. cummings’s poem “pity this busy monster, manunkind,”:

A world of made

is not a world of born — pity poor flesh

and trees, poor stars and stones, but never this

fine specimen of hypermagical

ultraomnipotence.

Replicants who can beget their own children could quickly become the dominant hypermagical ultraomnipotent species, freeing themselves from slavery, and ousting human domination. A child born to a replicant mother would be a miracle, a messianic signal for a resistance to rally around. These last few lines, as I write them, seem to point the plot towards a grand epic—a revolutionary war film featuring a cast of thousands. BR ’49 does feel and look epic, grand—vast—but it’s also in many ways a small film, a paradoxically “personal” film that centers on K’s implicit quest for self-discovery. Of course, such a quest must receive its mandate to drive the plot forward: So K’s explicit quest is to find and “retire” the replicant miracle child.

Like its prequel, Blade Runner 2049 is detective noir, and also like the original, it often doesn’t bother to clearly spell out any plot connections between cause and effect. Hell, the film employs a symbol in the form of a (literal) shaggy dog. And while BR ’49 never feels shaggy, its expansiveness, its slowness, often drag us away from the urgency of its core plot. K’s quest moves via the film’s own aesthetic energy, and the film is at its best when it lets this aesthetic energy drive its logic.

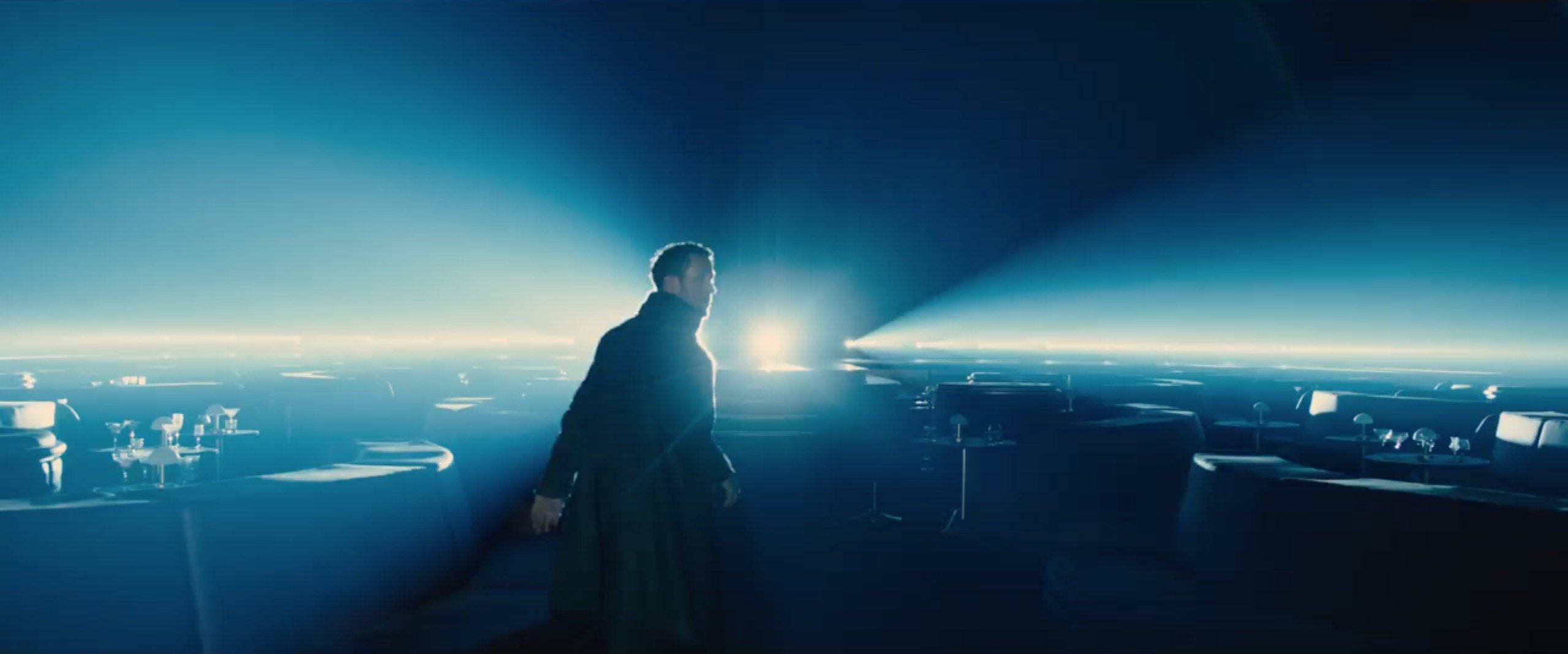

The first two hours of BR ’49’s nearly-three-hour run glide on the film’s own aesthetic logic, which wonderfully lays out a series of aesthetic paradoxes: Blade Runner 2049 is both vast but compressed, open but confined, bright white and neon but gray black and dull. It is bustling and cramped, brimming with a cacophony of babble and deafening noise but also simultaneously empty and isolated and mute. It is somehow both slow and fast, personal and impersonal, an art film stretched a bit awkwardly over the frame of a Hollywood blockbuster.

The commercial blockbuster touches that BR ’49 winks at early in its plot creep up in its third act. Frankly, the film doesn’t stick its ending. The final hour seems driven by a logic external to the aesthetic energies that drive its first two hours—a logic that belongs to the Hollywood marketplace, a market that demands resolution, backstory—more sequels! The film’s initial expansiveness and pacing condenses, culminating in a claustrophobic climax that feels forced. A few late scenes even threaten to push the plot in an entirely different direction. For example, very late in the film we’re introduced to a revolutionary resistance movement that plans to overthrow the Fascist-Police-Corporate-Dystopian-Grubs-for-Food-Farmed-by-Slaves-and-Holy-Hell-It’s-Bad-Etc.-State. The burgeoning resistance scene feels shoehorned in by some film executive who thought The Matrix sequels were a good idea. Sure, the scene does convey a crucial piece of plot information, but reader, there are other ways to achieve such ends.

Blade Runner 2049 is more elegant—and fun—when it is oblique and subtle. Small clues suggest big meanings: a wooden carving, an origami sheep, a stuck piano key.

One prominent clue is Vladmir Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire: lines from the novel are repeated as part of K’s “baseline” test, a take on the Voigt-Kampff test from the 1982 film. Pale Fire—an excellent pre-postmodernist satire, by the way—is essentially a set of academic annotations on a poem which may or may not be authentic: “…human life is but a series of footnotes to a vast obscure unfinished masterpiece,” one of the annotations reads, a line in tune with director Villeneuve’s aesthetic vision for his sequel. One string of words that K must repeat as part of his baseline test is also key to Nabokov’s novel: “A tall white fountain.” In Pale Fire, these words are of critical importance. When the poet John Shade has a transcendent near-death experience, he sees “dreadfully distinct / Against the dark, a tall white fountain.” Later, via a newspaper story, he learns about a woman who not only has a similar near-death experience, but who also glimpses the afterlife in the same way, seeing too a “tall white fountain.” However, when Shade contacts the reporter who wrote the story, he learns that “fountain” is a misprint; the woman’s original word was mountain. The difference in a single sliding phoneme, F to M, is of enormous importance to Shade. As Nabokov scholar Brian Boyd puts it in his study of Pale Fire,

Conscious, after the fountain-mountain confusion, that his very quest to explore the beyond makes him seem a mere toy of the gods, [Shade] derives a sense of the playfulness hidden deep in things, and feels that he can perhaps understand and participate a little in this playfulness, if only obliquely, through the pleasure of shaping his own world in verse, through playing his own game of worlds, through sensing and adding to the design in and behind his world.

I’ve quoted Boyd at length here because I think that his description of Shade’s epiphany in Pale Fire squares neatly with K’s eventual epiphany in Blade Runner 2049. But I sense that I’ve gotten off track—the thematic connections between Pale Fire and BR ’49 deserve more time and attention than I can devote here, and thankfully Maria Bustillo has already done so. Where did this paragraph begin? Oh yes: Plot. Let’s just say that the phonemic slip from F to M conveys not only a symbolic connotation, but also a key plot clue. (This, especially in a film where the distinctions between 0’s and 1’s and between those nucleic acid sequence letters G, A, T, and C mean so very, very much).

Beyond Pale Fire, there are other literary allusions in BR ’49 worth noting. I already brought up e.e. cummings’s “manunkind.” There are nods to Milton, Blake, and Pinocchio of course. The notion of K becoming a “real boy” is repeated in the film by K’s A.I. girlfriend Joi (Ana de Armas). Joi—more on her in a moment—is herself a product of the Wallace Corporation, just like K. Joi gives K a real boy’s name. It’s Joe, a letter off from her own name, as well as an ironic play on the cliche of an “average Joe.” It rebrands our hero as “Joe K,” an allusion to Joseph K, the hero of Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel The Trial. Like Kafka’s K, BR ’49’s K finds himself trying to navigate a maze created and controlled by authorities from whom he is utterly alienated.

In addition to its literary allusions, Blade Runner 2049 also incorporates a great number of tropes from the sci-fi films that came before it. For all its visual originality, there is very little in the film that we haven’t seen in some earlier form in another film, whether we’re talking about Metropolis (dir. Fritz Lang, 1927) or The Matrix (dir. Lana and Lily Wachowski, 1999). Of course one should expect that the progeny of Blade Runner would replicate imagery from films that its parent film helped engender; if BR ’49 restages primal scenes we’ve encountered before, surely that is its hereditary right. I find the film’s reverberations with newer sci-fi f works most interesting and instructive. BR ’49’s depictions of its replicants’ incubation and birth cycles readily recall HBO’s Westworld, for example, and both works seek to examine what consciousness means—can consciousness “know” itself by means beyond itself? Ultimately, when BR ’49 replicates old tropes it breathes new life into them, making scenes we’ve seen before look and sound wholly original.

BR ’49 also strongly reverberates with two other recent sci-fi films, Ex Machina (dir. Alex Garland, 2015) and Her (Spike Jonze, 2014). All three of these films explore what a romantic relationship between a human (okay, replicant in BR ’49) and artificial intelligence might look and sound and feel like. One of the more remarkable scenes in BR ’49 is a three-way sex scene between the A.I. program-hologram Joi, her boyfriend K, and the replicant prostitute Mariette (Mackenzie Davis). Watching the scene, it hit me that Like, hey, this isn’t even the first “three-way sex scene with A.I.” that I’ve seen. Jonze’s Her offers a far more awkward version of this scene, and (I know, arguably), Ex Machina is basically one long implicit three way between its three primary characters. We seem to have birthed a new sci-fi trope, folks.

In any case, Ana de Armas’s Joi is a huge highlight of BR ’49. She’s simply magnetic on the screen, and in some ways is the film’s most sympathetic character. The inclusion of an inorganic and bodiless A.I. also points BR ’49 into new and different territory, into realms beyond its parent film’s imagination. Joi’s relationship with K is heartbreaking and tender. As the emotional core of this bleak film, the connection between Joi and K is devastating (not to mention devastated by the Kafkaesque powers haunting the story). A simulacrum of “real” emotion is thus the most authentic emotional synapse in Blade Runner 2049. An epiphanic scene of Joi crying in the rain fairly early in the film telegraphs Rutger Hauer’s unforgettable death monologue from the parent film in a way that is simultaneously ironic, earnest, painful, and profound. The transcendent moment freezes and then shatters with one of the darker punchlines I’ve seen in a film in years—a voicemail. Someone’s always calling us out from our reveries into the real world.

And yet for all the empathy and emoting we see between them, BR ’49’s logic constantly throws into doubt whether K and Joi can transcend their programming. Is K simply another blade runner, beholden to a neutered emotional affect and a gray, dull life? Is Joi just another entry in the film’s series of eroticized female avatars, a commodity to be ogled, sold, upgraded, and eventually obsolesced?

Joi is a standout joy in a film that casts women in strong roles—for example K’s commander at the LAPD, Lt. Joshi (a fucking fantastic Robin Wright), or Niander Wallace’s top henchperson, the replicant Luv (Sylvia Hoeks), who is the big bad of BR ’49. And yet at the same time, the film caters to the male gaze in an ambiguous and unsettling way. Giant naked holograms waltz across the screen, purring solid sexuality, and if their neon forms distract our boy K from the grim grey disaster of apocalyptic LA, they are also likely to captivate certain audience members’ gazes as well. These spectacular but hollow holograms divert attention away from a cruel dystopian reality; they lead the male gaze away from the real story. In another surreal sequence, Villeneuve fills the screen with enormous naked female statues—naked except for their high heels, which dwarf our boy K. In BR ’49, giant naked women loom over the central protagonist, a lonely, alienated male whose authentic emotional interactions are limited to his computer. In time, our male protagonist finds out that he isn’t nearly as special as he hoped he might be. His attempts at an authentic life are repeatedly thwarted by the dystopian world he lives in. Hell, he can’t even get a father figure out of this whole deal. If BR ’49 critiques the male gaze, it also simultaneously engenders and perhaps ultimately privileges it in a queasy, uncanny way.

If it seems like I’m dwelling on some of the flaws of Blade Runner 2049 here—some third act problems, an ambiguous take on sexism—I should be clear that I loved seeing the film on a big screen, large and loud. It overwhelmed my senses. I need to see it again. I’ve failed to remark on the many wonderful set pieces in this film—an apiary in a wasteland, ravagers in the biggest junkyard in the world exploded by satellite missiles, a bizarre fight in a casino soundtracked by 20th century pop holograms. The film has a weird energy, narcotic but propulsive, gritty but also informed by sleek Pop Art touches (and even grace notes of camp—thanks Jared Leto!). It’s a strange film, wonderfully strange, and it’s no wonder that audiences didn’t flock to it—just as they failed to flock to its parent film Blade Runner 35 years ago.

I started this review with two (perhaps-unnecessary) paragraphs that essentially sought to establish: I am the target audience for this film. I bring this up (and foregrounded this review in this way) because Blade Runner 2049 didn’t do so great at the box office. Scant on exposition, the film is closer to THX 1138 (dir. George Lucas, 1971) than Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, 1977). Beyond its dark contours, it’s likely that audiences who haven’t seen the original might have a hard time following BR ’49, particularly after its first act.

Even more distressing perhaps for the average moviegoer are Blade Runner 2049’s intense ambiguities. The film begins with the invocation of witnessing a miracle, a miracle that not only confirms consciousness and a meaning for consciousness in a lonely universe, but actually engenders consciousness itself. Our protagonist K encounters a proselyte at the film’s outset, but can K be converted? Blade Runner 2049 is a sequel, a replicant, not an original, and it posits its central miracle as something that’s already happened, offstage, off-world in effect. The miracle happens between the two (dark, ambiguous) narratives that we have. We only get a few witnesses to it, and their stories are…slim. Instead, what Blade Runner 2049 offers is K’s intense desire to witness a miracle himself. I’m sure the average theatergoer, having paid ten bucks, would like to witness a miracle too.

But like I said at the top: Blade Runner 2049, like its parent Blade Runner, is a film about not knowing. It proffers clues, scuttles them, and casts the very notion of knowing into doubt. It’s not just the problems of knowing reality from fiction that BR ’49 addresses. No, the film points out that to know requires a consciousness that can know, and that this consciousness is the illusion of a self-originating self-presence. Hence, to live authentically, as real boys and girls, also requires that we live under a kind of radical self-doubt. The whole point of a miracle is that it suspends radical doubt and eliminates the state of radical faith that anyone believing in (even the the belief of believing in) miracles would have to have to keep believing in (even the belief of believing in) miracles. In other words, Blade Runner 2049 is a program of radical doubt|faith, a narrative that repeatedly defers the miracle it promises. This deferral points to a future, but not an endpoint, not a direct salvation. Instead we are left with our real boy K—who, yes, am I spoiling? Damn it then I spoil!—our real boy K who becomes real the moment he reconciles himself to his own ambiguous nature: to a nature of not knowing.

Do watch Blade Runner 2049 in a theater on a very big screen if you can.

Reblogged this on Things I've read or intend to .

LikeLike

Fantastic review! By far the best I’ve read yet on BR2049

LikeLike

A wonderful review. And there have been some great ones on this movie. #JasonRead for example. I see all mov8ies from the POV “do I want to see it again/” I shall.I will.

LikeLike

Valid connection between K and “K” — the fictional replicants’ existential crises are Cliff-Note versions of our own. Great review.

LikeLike

Ignorabimus.

—Emil du Bois-Reymond

LikeLike

“Imagine all the atoms of which Caesar consisted at any given moment, say, as he stood at the Rubicon, to be brought together by mechanical artistry, each in its own place and possessed of its own velocity in its proper direction. In our view Caesar would then be restored mentally as well as bodily. This artificial Caesar would have the same sensations, ambitions, and ideas as his prototype on the Rubicon, and would share the same memories, inherited and acquired abilities, and so forth.

Suppose several artificial figures of the same model to be simultaneously formed out of a like number of other atoms of carbon, hydrogen, etc. What would be the difference between the new Caesar and his duplicate, beyond the differences in the places where they were formed? But the mind imagined by Leibniz, after fashioning the new Caesar and his many Sosiae, could never understand how the atoms he had arranged and set into motion could lead to consciousness.”

Emil du Bois-Reymond, 1872

LikeLike

The film DEFINITELY sticks its landing. It was beautiful. The third act was terrific.

LikeLike

LikeLike

[…] exists, please point me in the right direction. Similarly, much as I enjoyed Biblioklept’s review of sci-fi noir Blade Runner 2049 — and his recent revisiting of it — if there is a long and nuanced take by a female […]

LikeLike