This weekend I picked up a new audiobook collection of Robert Coover short stories which has been titled Going for a Beer (presumably because “Going for a Beer” is a perfect short story). The audiobook contains 30 stories and is read by Charlie Thurston, a more than capable as an orator.

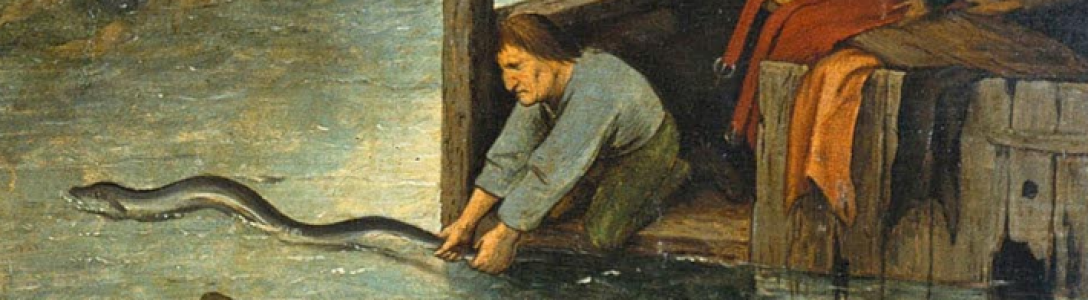

The opening story is one of Coover’s earliest published stories. “The Brother” (1962) retells the Noah narrative from the book of Genesis. I just wrote “retells,” but that’s not really the right term. Instead of retelling the story of Noah and the ark and YHWH’s flood, Coover imagines the apocalyptic affair from the perspective of Noah’s younger brother, who narrates this tale.

Noah’s unnamed brother is an earthy, sensual fellow who loves his wife and loves his wine. His wife—a sympathetic and endearing figure—is pregnant with their first child. They’re already picking out names (“Nathaniel or Anna”). Brother Noah keeps taking the narrator from his own familial duties to help build a boat though:

right there right there in the middle of the damn field he says he wants to put that thing together him and his buggy ideas and so me I says “how the hell you gonna get it down to the water?” but he just focuses me out sweepin the blue his eyes rollin like they do when he gets het on some new lunatic notion and he says not to worry none about that just would I help him for God’s sake and because he don’t know how he can get it done in time otherwise and though you’d have to be loonier than him to say yes I says I will of course I always would crazy as my brother is I’ve done little else since I was born and my wife she says “I can’t figure it out I can’t sec why you always have to be babyin that old fool he ain’t never done nothin for you God knows and you got enough to do here fields need plowin it’s a bad enough year already my God and now that red-eyed brother of yours wingin around like a damn cloud and not knowin what in the world he’s doin buildin a damn boat in the country my God what next? you’re a damn fool I tell you” but packs me some sandwiches just the same and some sandwiches for my brother

That’s kinda-sorta the opening paragraph—although no it’s not, because the whole story is just one big paragraph, a big oral fragment really, which begins with a lower-case r and keeps going in a verbal rush whose only concessions to punctuation are question marks and quotation marks. No periods or commas here folks. On the page, “The Brother” perhaps approximates the blockish brickish look of a Gutenberg Bible or even the Torah, neither of which give the reader a nice period to rest on, let alone a friendly pause between paragraphs.

“The Brother” might be typographically daunting, but the apparent thickness of verbal force on the page belies its oral charms. The story is meant to be read out loud. Hell, it’s biblical, after all—a witnessing. Read aloud, “The Brother” shows us a deeply sympathetic pair of characters, a husband and wife whose small pleasures, telegraphed in naturalistic speech, might remind the auditor of real persons living today. And yet there’s an apocalyptic backdrop here. Noah’s brother and Noah’s brother’s wife—and their unborn child, and all the unborn children—will not survive YHWH’s flood.

Coover does not paint Noah as anything but a shrugging reluctant weirdo. He’s no prophet who warns and helps his brother, but rather a defeated man:

and it ain’t no goddamn fishin boat he wants to put up neither in fact it’s the biggest damn thing I ever heard of and for weeks wee\s I’m tellin you we ain’t doin nothin but cuttin down pine trees and haulin them out to his field which is really pretty high up a hill and my God that’s work lemme tell you and my wife she sighs and says I am really crazy r-e-a-l-l-y crazy and her four months with a child and tryin to do my work and hers too and still when I come home from haulin timbers around all day she’s got enough left to rub my shoulders and the small of my back and fix a hot meal her long black hair pulled to a knot behind her head and hangin marvelously down her back her eyes gentle but very tired my God and I says to my brother I says “look I got a lotta work to do buddy you’ll have to finish this idiot thing yourself I wanna help you all I can you know that but” and he looks off and he says “it don’t matter none your work” and I says “the hell it don’t how you think me and my wife we’re gonna eat I mean where do you think this food comes from you been puttin away man? you can’t eat this goddamn boat out here ready to rot in that bastard sun” and he just sighs long and says “no it just don’t matter” and he sits him down on a rock kinda tired like and stares off and looks like he might even for God’s sake cry

Noah’s dismissing his brother’s work strikes me as utterly cruel—he makes no attempt to explain why his brother’s efforts at creating a better world are in vain. I shared the passage at length again in part because I hope you’ll read it aloud gentle reader, but also that you’ll note that maybe you didn’t note all its blasphemies—Coover’s story is larded with “my Gods” and “damns” and “goddamns,” no different than the speech of 1962, no different than the speech of 2018.

Coover gives us a narrator like us, human, earthly, driven by simple pleasures and a basic sense of love. Noah comes off like a prick. The Bible loves its heroes, but the ordinary folks don’t even get to live in the margins. There’s more morality in orality though—in conversation and communication and talk.

You don’t have to buy the audiobook though to hear “The Brother.” Here is Coover reading it himself:

Listening to Coover read it through is pretty special. You’re right about it having to be read aloud. I had to go straight over to the “Going for a beer” link and read that one as well, and it’s just as good. Thanks for sharing

LikeLike

[…] The Brother. (listen) […]

LikeLike