It seems that for the past two weeks I have been reading mostly final exams and research papers, but I have read some other things too.

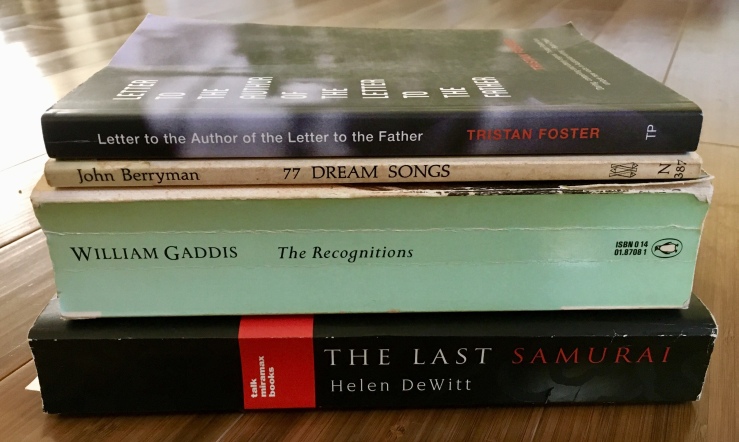

I have all but finished Tristan Foster’s collection Letter to the Author of the Letter to the Father, which I think is excellent contemporary fiction. Foster’s pieces do things that I did not know that I wanted contemporary fiction to do until I read the pieces. Read his story/poem/thing “Economies of Scale” to get an illustrating example. Letter to the Author of the Letter to the Father deserves a proper review and I will give it one sooner rather than later. For now let me say that I am jealous of that title.

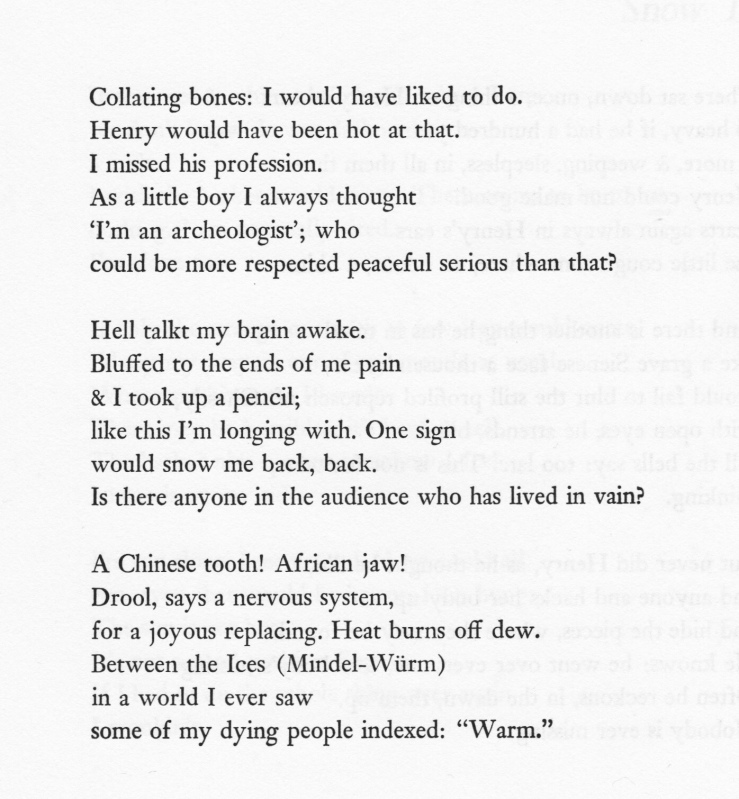

I’ve continued sifting unevenly through John Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs. Earlier this year I tried reading one Dream Song a day and then realized I didn’t like reading one Dream Song a day. Some days I wanted to read three or five and some days I wanted to read none and some days I felt like skipping ahead to later Dream Songs and some days I got stuck on a few lines or a spare image or an oblique word and then I couldn’t move on. Here is Dream Song 30, which took me two days to read (I got hung up on “Hell talkt my brain awake” for more than a little while):

I am still auditing/rereading William Gaddis’s first novel The Recognitions. I riffed on rereading it here and here and here) and hope to riff some more, but I doubt I’ll have anything comprehensible to write about the chapter I just finished, II.3 (Chapter 3 of Section II). The opening of this chapter is a stream-of-consciousness flowing so freely that it overwhelms the reader. Gaddis takes us into Wyatt’s addled brains, a space overstuffed with hurtling esoteric mythopoetic gobbledygook. (The section also strongly recalls Stephen Dedalus’s stroll on the beach in Chapter 3 of Ulysses—although Gaddis denied having read Joyce’s opus).

The interior of Wyatt’s skull is frustrating as hell, which is maybe half the point. Things don’t get any simpler when Wyatt goes to his childhood home where no one recognizes him. Or, rather, he is misrecognized, recognized as someone else: an acolyte of Mithras, Prester John, the Messiah. As always with The Recognitions though, there’s a radical ambiguity: Is Wyatt misrecognized? Or is there an originality under the surface that his ersatz fragmented family recognizes?

I have around 100 more pages left to read of Helen DeWitt’s debut novel The Last Samurai. I’ve read the book at such a fast clip that I’m frankly suspicious of it. The book is 530 pages but feels like its 150 pages. I’m not sure what that means. Maybe it means it’s not a particularly dense novel, although it is rich in ideas—ideas about art, language, family. The book won me over when DeWitt steers the narrative into one of its first major side quests, the story of a musician named Kenzo Yamamoto. I recall reading late into the night, overtired but unable to put the book down. I stayed up too late and was too tired the next day, and then sneaked in a few sections during office hours the next morning. I think that means that I like the book very much—but I also find myself irked at times by something in DeWitt’s style—a sort of archness that veers into preciousness, a cleverness that interminably announces itself. The book tries to spin irony into earnestness, which is vaguely exhausting. I think I would have been head over heels in love with this book if I had read it ten or fifteen years ago.

In his recent review of The Last Samurai at Vulture — where the book garnered the dubious prize of being prematurely called “The Best Book of the Century” — Christian Lorentzen wrote that DeWitt’s “novel was never easily subsumed in one of the day’s critical categories, like James Wood’s hysterical realism.” But reading The Last Samurai, I am reminded of the books that Wood thought of as “hysterical realism.” Wood coined the term to describe a trend he saw in literature of the late nineties, literature that combined absurdity with social and cultural realism (at the expense of Wood’s precious psychological realism). Wood specifically applied his description to Zadie Smith’s novel White Teeth (published, like The Last Samurai, in 2000), but slapped it down elsewhere, notably to David Foster Wallace. While I don’t endorse Wood’s scolding use of the phrase “hysterical realism,” I do think that it’s a useful (if perhaps too-nebulous) description for a set of trends in some of the major novels published in the late nineties and early 2000s: Infinite Jest, Middlesex, The Corrections, A Heartbreaking Work of Something or Other, etc. And, to come in where I started: The Last Samurai shares a lot of the same features with these texts—the blending of styles and texts and disciplines, etc. DeWitt’s filtering a lot of the same stuff, I guess. I would maybe use the term post-postmodernism in place of “hysterical realism” though—although a novel need not be subsumed by any term, and maybe the best can’t really be described in language at all.

Your appreciation and comments about Last Samurai resonate. I also raced through with gusto, enjoying every moment, but, yes, would’ve loved the book ten years ago. I think Lightning Rods the better book. Both stories remind me of A. M. Homes, although her work is much darker. Not that I can read Homes anymore. I found DeWitt’s recent short story collection unreadable.

LikeLike

I found myself unable to keep going with Some Trick, which strikes me as too-precious…and I didn’t really like Lightning Rods (although I loved the first 70 pages or so). I ended up digging TLS fine enough, but it’s a bit too-clever for me. I loved some of the sections though.

LikeLike