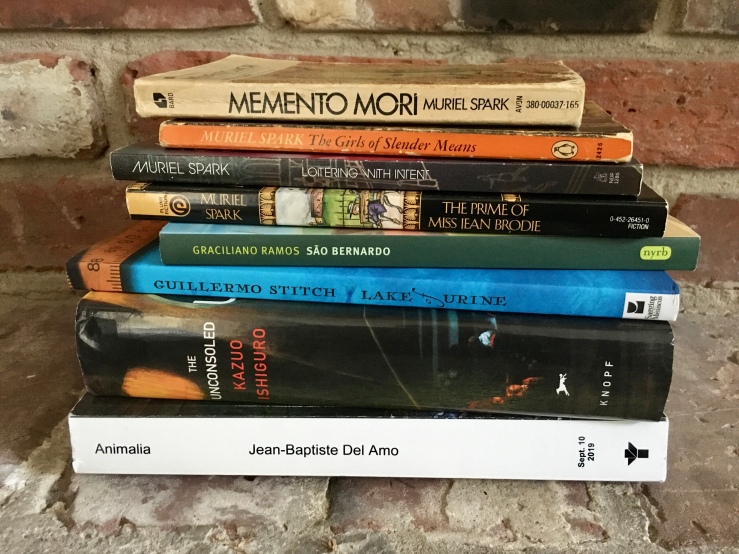

From bottom to top:

I finally started Jean-Baptiste Del Amo’s Animalia last week. I took the book with me to a place we rented near Black Mountain, North Carolina for a week. I purposefully took only Animalia, leaving behind two books I was in the middle of—Muriel Spark’s Loitering with Intent and Guillermo Stitch’s Lake of Urine. I used the adverb purposefully in the previous sentence, although I’m not sure what my purpose was. I think I just wanted an associative break from the past few months. I read geographically, even in my own home. I read the first section of Animalia, often overwhelmed by its abject lifeforce. The novel begins in rural southwest France at the end of the nineteenth century, focusing on a family farm. The preceding sentence is a bad description: Animalia is, so far anyway, a visceral, naturalistic, and very precise rendering of humans as animals. I don’t think I’ve ever been as intrigued as to how a novel was translated, either. In Frank Wynne’s English translation, Del Amo’s prose carries notes and tones evocative of Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy. Del Amo employs precise Latinate words, using, for example, genetrix, instead of mother, as in this paragraph:

The genetrix, a lean, cold woman, with a ruddy neck and hands that are ever busy, affords the child scant attention. She is content merely to instruct her, to pass on the skills for those chores that are the preserve of their sex, and the child quickly learns to emulate her in her tasks, to mimic her gestures and her bearing. At five years old, she holds herself stiff and staid as a farmer’s wife, feet planted firmly on the ground, clenched fists resting on her narrow hips. She beats the laundry, churns the butter and draws water from the well or the spring without expecting affection or gratitude in return. Before Éléonore was born, the father twice impregnated the genetrix, but her menses are light, irregular, and continued to flow during the months when, in hindsight, she realizes that she was pregnant, though her belly had barely begun to swell. Although scrawny, she had a pot-belly as a child, her organs strained and bloated from parasitic infections contracted through playing in dirt and dungheaps, or eating infected meat, a condition her mother vainly attempted to treat with decoctions of garlic.

The paragraph, from early in Animalia, conveys the prose’s abject flavor. Read the rest of the excerpt at Granta.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled is over 500 pages but somehow does not read like a massive novel, partly, I suppose, because the novel quickly teaches you how to read the novel. The key for me came about 100 pages in, when the narrator goes to a showing of 2001: A Space Odyssey starring Clint Eastwood and Yul Brynner. There’s an earlier reference to a “bleeper” that stuck out too, but it’s at the precise moment of this alternate 2001 that The Unconsoled’s just-slightly-different universe clicked for me. Following in the tradition of Kafka’s The Castle, The Unconsoled reads like a dream-fever set of looping deferrals. Our narrator, Ryder, is (apparently) a famous pianist who arrives at an unnamed town, where he is to…do…something?…to help restore the town’s artistic and aesthetic pride. (One way we know that The Unconsoled takes place in an alternate reality is that people care deeply about art, music, and literature.) However, Ryder keeps getting sidetracked, entangled in promises and misunderstanding, some dark, some comic, all just a bit frustrating. There’s a great video game someone could make out of The Unconsoled—a video game consisting of only side quests perhaps. Once the reader gives in to The Unconsoled’s looping rhythms, there’s an almost hypnotic pleasure to the book. Its themes of family disappointment, artistic struggle, and futility layer like musical motifs, ultimately suggesting that the events of the novel could take place entirely in Ryder’s consciousness, where he orchestrates all the parts himself. Under the whole thing though is a very conventional plot though—think a Kafka fanfic version of Waiting for Guffman. I loved it.

I will be posting a proper review of Guillermo Stitch’s Lake of Urine some time this month, so I won’t remark at length on it. I’m a little under halfway through (had to restart after returning from the mountains), and it seems to me that the plot is impossible to describe. Or maybe it’s really simple: A rural couple, Norabole and Bernard, escape from their small town and move to the big city (“Big City”). Norabole very quickly becomes the CEO of a huge company, with an eye toward creating “the world’s first Gothic conglomerate” (she plans to get an exorcist on the board, as well as having the company partake in an annual seance). Meanwhile, Bernard struggles to find employment and whips up seven course meals for his Noarbole. He also has apparently contracted (contracted?!) xenoglossia. Lake of Urine is energetic and very funny and so so weird. Stitch seems to be doing whatever he wants on the page and I dig it.

I really enjoyed Graciliano Ramos’s novel São Bernardo (new translation by Padma Viswanathan), mostly for the narrator’s voice (which reminded me very much of Al Swearengen of Deadwood). Through somewhat nefarious means, Paulo Honorio takes over the run-down estate he used to toil on, restores it to a fruitful enterprise, screws over his neighbors, and exploits everyone around him. He decries at one point that “this rough life…gave me a rough soul,” which he uses as part confession and part excuse for his failure to evolve to the level his younger, sweeter wife would like him to. São Bernardo is often funny, but has a mordant, even tragic streak near its end. Ultimately, it’s Honorio’s voice and viewpoint that engages the reader. He paints a clear and damning portrait of himself and shows it to the reader—but also shows the reader that he cannot see himself. Good stuff.

Four by Muriel Spark. I’d never read her until May, and I’ve just been gobbling these up. I started with The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which is fantastic, and then read The Girls of Slender Means, which I liked even more than Prime. Slender Means unself-consciously employs some postmodern techniques to paint a vibrant picture of what the End of the War might feel like. The novel unexpectedly ends in a negative religious epiphany. (And the whole thing coincides with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) I then read Loitering with Intent, which is my favorite so far—just sharp as hell, and chock full of patterns and loops that I want to go back to again. I definitely will reread that one. I’m near the end of Memento Mori, a novel that concerns aging, memory, loss, and coming to terms with death. I was surprised to learn that this was Spark’s third novel, and that she would’ve been around 41—my age—when it was published. Most of the characters are over seventy, and Spark seems to inhabit their consciousness with a level of acuity that surprises me. Memento Mori is sharp and witty, but, barring some last minute shift, it’s not been my favorite Spark—but it’s still very good, and I want to read more. Any suggestions?

Glad you liked the Unconsoled Have you read The Peregrine by J.A. Baker?

Francisco

>

LikeLike

“Animalia” looks interesting; strong paragraph. Cheers, Edwin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read what you have of Spark, plus A Far Cry from Kensington, which I also consider essential; beyond that, I’m also curious what might be of that caliber.

LikeLike

Which was your favorite of the five? Is A Far Cry on par with Girls or Loitering?

LikeLike

I found all of them excellent, The Prime primus inter pares; as for A Far Cry, I’ve seen it described as less astringent than her other work, which is saying something. Loitering was my introduction, long before the others …

LikeLike

doubling back to link a more comprehensive oeuvreview:

https://philipchristman.com/2014/06/27/muriel-sparks-novels-ranked/

The Ballad of Peckham Rye tempts most, but I’m hesitant, feel as though I’ve hit the high points.

LikeLike

The Driver’s Seat and A Far Cry From Kensington are the two Sparks I’ve read that I think approach Brodie and Slender Means in quality. The former in particular is wonderfully weird.

LikeLiked by 1 person