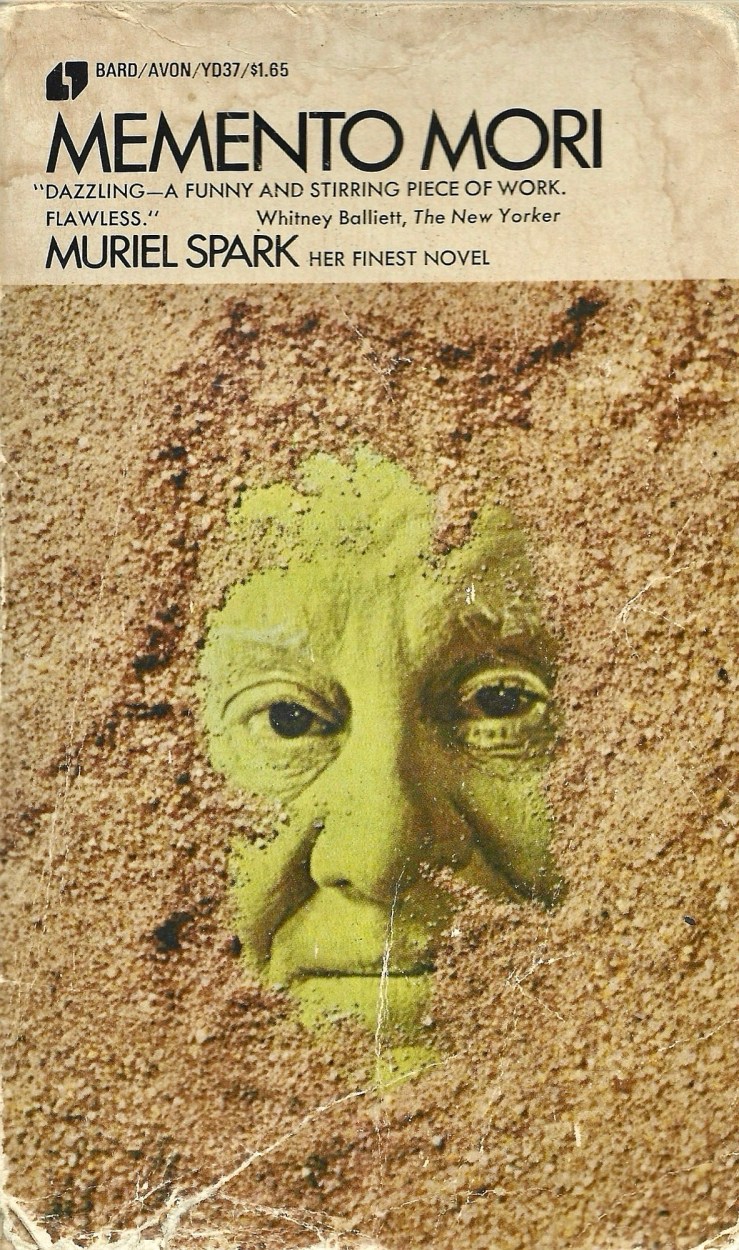

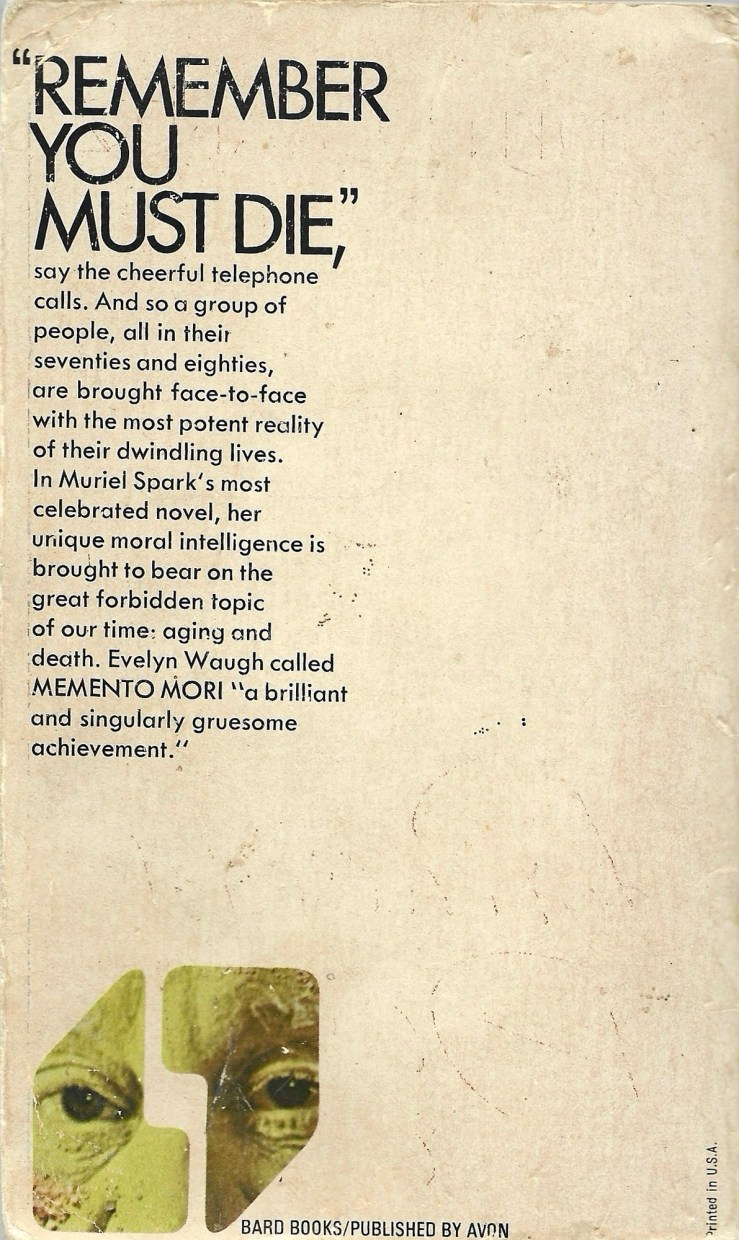

Memento Mori, 1954, Muriel Spark. Avon Bard (1978). No cover artist or designer credited. 191 pages.

From David Lodge’s 2010 reappraisal of the novel in The Guardian:

The fiction of the 50s was dominated by a new wave of social realism, represented by novels such as Lucky Jim, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and Room at the Top, whose originality lay in tone and attitude rather than technique. Typically they were narrated in the first person or in free indirect style, articulating the consciousness of a single character, usually a young man, whose rather ordinary but well observed life revealed new tensions and fault-lines in postwar British society. An unsympathetic character in Memento Mori called Eric has evidently written two dispiriting works of this kind. Memento Mori itself was an utterly different and virtually unprecedented kind of novel. It is a short book, but it has a huge cast of characters, to nearly all of whose minds the reader is given access. The speed and abruptness with which the narrative switches from one point of view to another, managed and commented on by an impersonal but intrusive narrator, is a distinguishing feature of nearly all Spark’s fiction, and it violated the aesthetic rules not only of the neorealist novel, but also of the modernist novel from Henry James to Virginia Woolf. Spark was a postmodernist writer before that term was known to literary criticism. She took the convention of the omniscient author familiar in classic 19th-century novels and applied it in a new, speeded-up, throwaway style to a complex plot of a kind excluded from modern literary fiction – in this case involving blackmail and intrigues over wills, multiple deaths and discoveries of secret scandals, almost a parodic update of a Victorian sensation novel. And she added to the mix an element of the uncanny, through which the existence of a transcendent, eternal and immaterial reality impinges on the lives of her ageing characters, reminding them of their mortality.