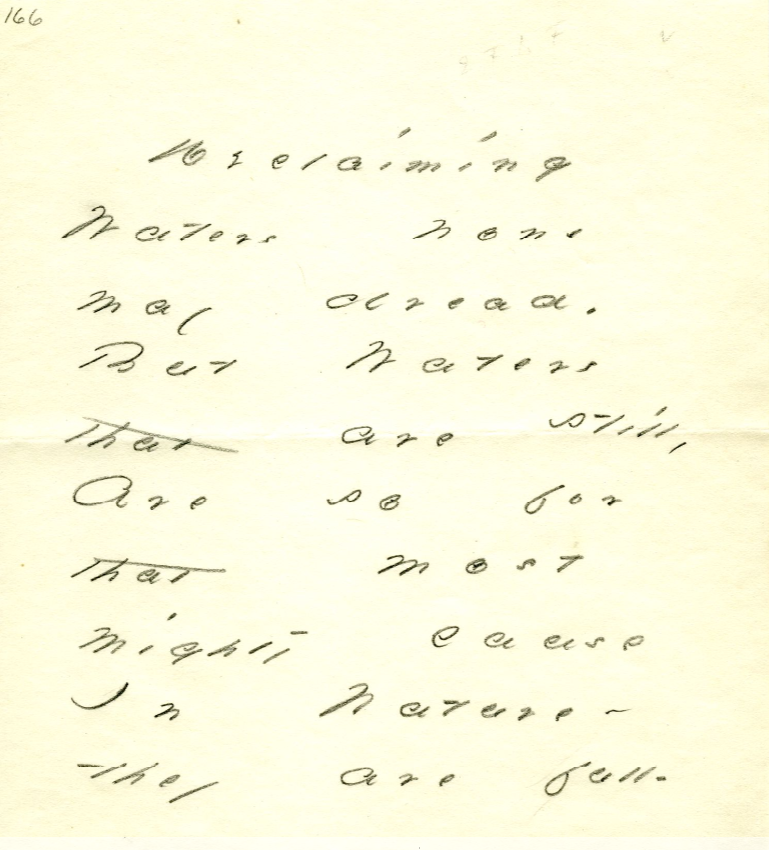

Declaiming Waters none may dread –

But Waters that are still

Are so for that most fatal cause

In Nature – they are full –

Declaiming Waters none may dread –

But Waters that are still

Are so for that most fatal cause

In Nature – they are full –

Departure, 1988 by Paula Rego (1935–2022)

“The Mushroom Drink of the Borgie Well”

from Scatalogic Rites of All Nations

by

Captain John Gregory Bourke

The following paragraph deserves more than a passing mention:—

“The Borgie well, at Cambuslang, near Glasgow, is credited with making mad those who drink from it; according to the local rhyme,

‘A drink of the Borgie, a bite of the weed,

Sets a’ the Cam’slang folk wrang in the head.’

The weed is the weedy fungi.”—(“Folk-Medicine,” Black, London, 1883, p. 104.)

Camden says that the Irish “delight in herbs, … especially cresses, mushrooms, and roots.”—(“Britannia,” edition of London, 1753, vol. ii. p. 1422.)

Other references to the Siberian fungus are inserted to afford students the fullest possible opportunity to understand all that was available to the author himself on this point.

“Agaricus muscarius is one of the most injurious, yet it is used as a means of intoxication by the Kamtchadales. One or two of them are sufficient to produce a slight intoxication, which is peculiar in its character. It stimulates the muscular powers and greatly excites the nervous system, leading the partakers into the most ridiculous extravagances.”—(American Cyclopædia, New York, 1881, article “Fungi.”)

Agaricus muscarius. “This is the ‘mouche-more’ of the Russians, Kamtchadales, and Koriars, who use it for intoxication. They sometimes eat it dry, and sometimes immerse it in a liquor made with the epilobium, and when they drink this liquor they are seized with convulsions in all their limbs, followed by that kind of raving which attends a burning fever. They personify this mushroom, and if they are urged by its effects to suicide or any dreadful crime, they pretend to obey its commands. To fit themselves for premeditated assassination they recur to the use of the ‘mouche-more.’ A powder of the root, or of that part of the stem which is covered by the earth, is recommended in epileptic cases, and externally applied for dissipating hard, globular swellings and for healing ulcers.”—(Cyclopædia, Philadelphia, no date, Samuel Bradford, vol. i. article “Agaric.”) Continue reading ““The Mushroom Drink of the Borgie Well” | From Captain John G. Bourke’s Scatalogic Rites of All Nations”

“The Birds”

by

Emmy Bridgwater

from

Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (ed. Penelope Rosemont)

“The Birds”

One

He pulled the blanket over and he drew up the blind. The yellow mice rushed into their corners. The spiders ran behind the pictures. The lecture began on Christ the Forerunner. Only the very young mice sat still to listen. The blackbirds flying near the window passed the word to each other. “Come on. Here we may find something. Something to put our beaks into.” Snap went the window cord; down came the blind. The birds, disappointed, did the best they could. They flew nearer and nearer the windowpane. It was dangerous. It wasn’t worth it. But they wanted to get the news—to be the first to know—to pass on the news. What had come to the lecture on Christ? Did one still lie under the blankets? The spiders laughed into their hands to think of the birds outside all twittering and over-anxious.

Two

As she walked into the garden the birds flew down to her pecking at her lips, “Don’t do that,” she cried, “It’s mine. I’m alive you know.” “Well, why don’t you wear colors?” She heard them talking. “Dead people walk, but they don’t wear colors. They scream and they talk too.” The birds went on chattering about dead people. They all perched up on the holly bush but they didn’t peck the soft berries. They just stared down at her. All of them stared with their little black beady eyes. They were looking at her red lips.

Three

“Sing a song for the King. Come on, now sing.” The child was shy to start, but her mother, standing behind her gave her a little push which startled her into opening her mouth and she began, “Wasn’t that a dirty dish to set before the king?” “Begin again dear,” whispered her mother, “at the first line,” “O.k. ma,” and she chanted, “Four and twenty black… oooh,” for a peacock had walked in front of her and spread out its tail and croaked “Frico. Frico.” The little girl went very white. “Frico. Frico,” she said. The birds, who had been sitting on the cornice as part of the decoration, flew down into the court and circled about the heads of the King and Courtiers, fluttering as close as possible. All the people flapped their hands helplessly. Suddenly the little girl pointed at the King. “You must get out of here,” she said in a grown-up voice. “This is their Palace.”

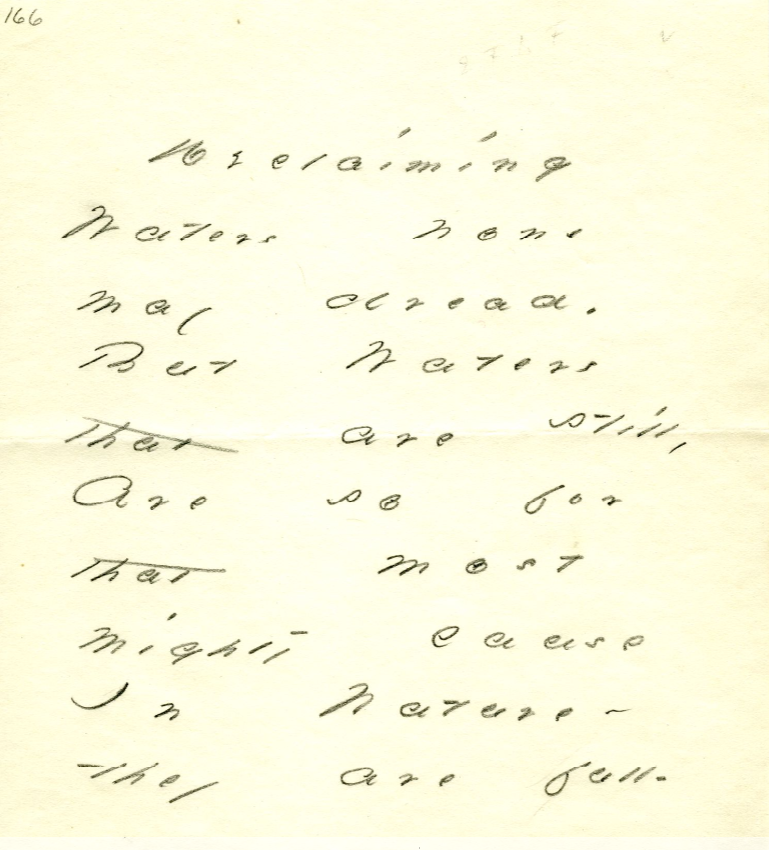

Morning, 1971 by John Koch (1909–1978)

Night, 1964 by John Koch (1909–1978)

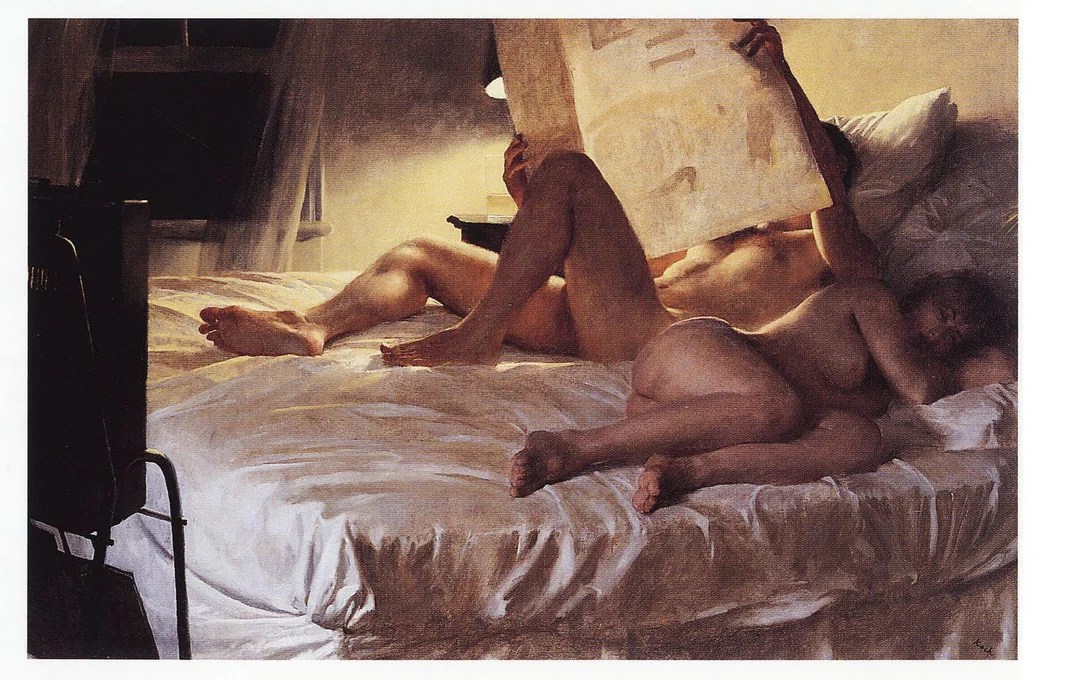

Melinda Gebbie’s cover for Wimmen’s Comix #7, December 1976, Last Gasp. Reprinted in The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Vol. 1, Fantagraphic Books.

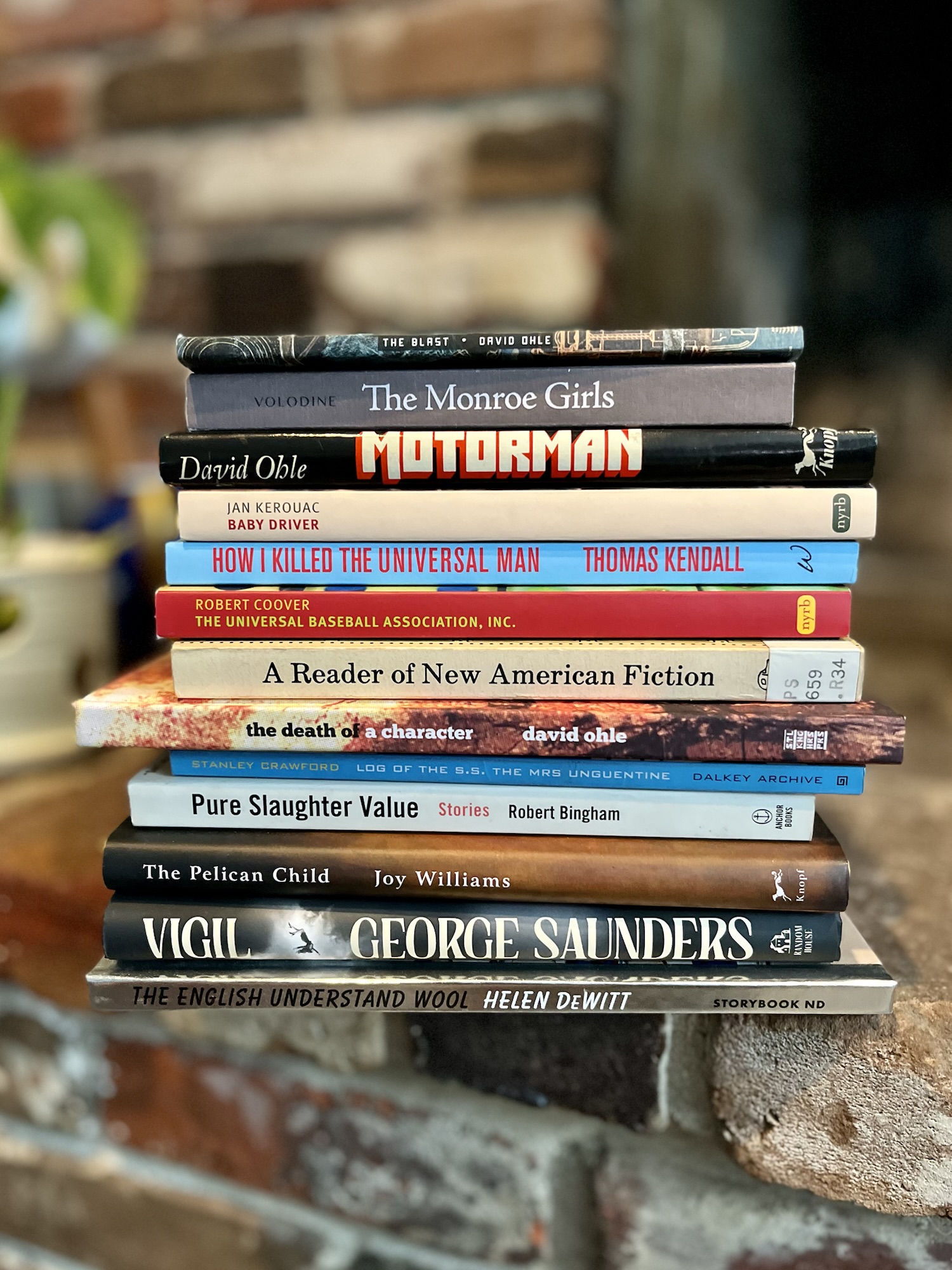

Joy Williams’ collection The Pelican Child was the first book I read this year. I picked up a copy back in December and surprised myself by reading most of it over a few days. It’s a much heavier collection than the wry vignettes of 2013’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God or its sequel, Concerning the Future of Souls (2024). The stories here alight on mortality, human ecological cultural aesthetic, etc. Opener “Flour” strikes me as a postmodern riff on Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” and the fable (literally fabulous?) closer “Baba Yaga and The Pelican Child” made me tear up a little and then hate myself a little. A book about death where young people, tattooed with the lines of long-dead poets, are the clean-up crew working the night shift sweeping up the detritus of the 21st century. (It was “Argos,” about Odysseus’s good and loyal boy, that really killed me if I’m honest.)

There are still a few stories at the back of Robert Bingham’s 1997 collection Pure Slaughter Value. I will tuck them away for another time. I loved these stories and then I found myself angry at his spoiled clever preppy narrators. “The Other Family” is one of the better stories I’ve read in a long time.

I reread Robert Coover’s second novel, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. (1968), back in January and made some notes for a review. This is not that review. I am not a Coover expert but I think this is as good an introduction to his novels as anything. (No it’s not; get Pricksongs & Descants.)

Speaking of Universal—I had an early misfire with Thomas Kendall’s 2023 novel How I Killed the Universal Man, but then started it again the other night with a perhaps clearer idea of what the author was trying to do. I think I was thinking something more straightforward, more cyberpunknoir, something less, I dunno, formally meta or post. More thoughts to come.

I think George Saunders’ new novel Vigil fucking sucks.

Is Helen DeWitt’s The English Understand Wool a novella? A novelette? A short story? Should we care? I loved The Last Samurai (2000), thought Lightning Rods (2011) seemed like a novel written quickly for money, and found myself embarrassed for everyone involved with her collection Some Trick (2018), including the editor, publisher, bookseller who sold it to me, and myself — but maybe I should go back and try it again? I thought The English Understand Wool was really good! It was funny and silly and sharp.

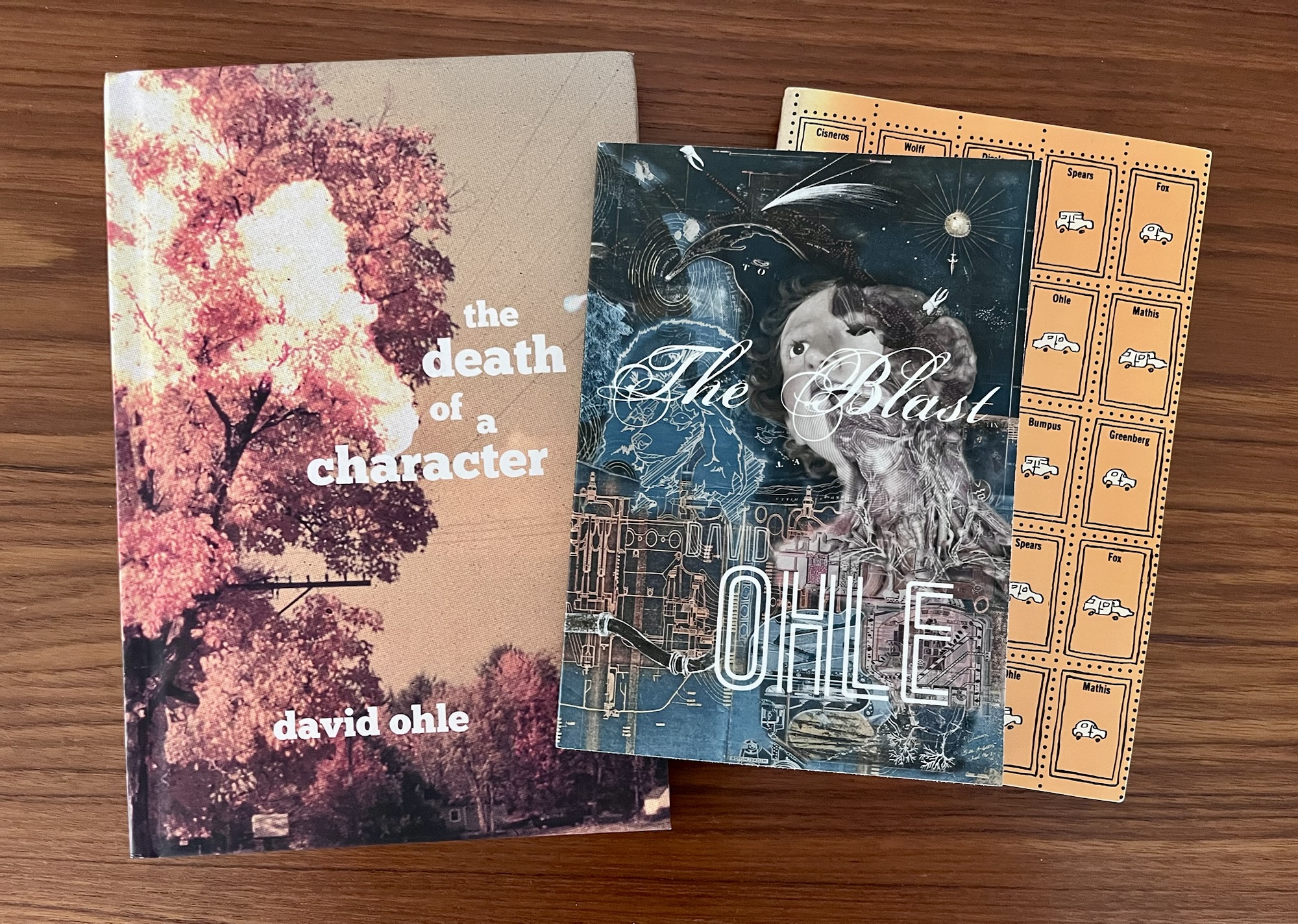

I have spent the past few months reading what I could get my little pink hands on of David Ohle’s incredible post-apocalyptic comedy, the Moldenke Saga (a term I have just now coined, maybe). I will do a Whole Thing on these novels at some point, but I read The Blast in one night and felt really sad that it was over and then the next night I read most of the last Moldenke novel, The Death of a Character, and then I woke up around 4am that morning and finished it and got a little choked up. In novels like Motorman, The Age of Sinatra, and The Old Reactor, Ohle has given us a fittingly grotesque, grody, gnarly, abject, hilarious, zany, and emotionally-resonant zombie funhouse mirror for our own gross times. These novels are woefully underread and still, for the most part, in print. Seek them out.

Wanting to scratch an Ohle itch, I turned to Literature Map to suggest some proxy; this machine offered Stanley Crawford as a proximal prosist. I picked up a few of his novels the other weekend, including 1972’s Log of the S.S. The Mrs Unguentine, which I read over the course of a few hours late at night and then reread the next night. It’s not like the Ohle oeuvre, excepting that it’s wholly, utterly original at the conceptual aesthetic rhetorical level, is generally tragicomical, mythical, epic — but also compact, and funny and alarming. So it’s very much in the Ohlesphere. Seek it out.

And also scratching that apocalyptic itch is Antoine Volodine’s 2021 novel The Monroe Girls (in translation by Alyson Waters). It’s got this cracked bifocal Bardo thing going on, which I will not explain here and now. The print in the Archipelago edition is small for my aging eyes. I’ve read it in the afternoon; it is not an afternoon book, it is a 2am book.

I read the first half of Jan Kerouac’s “semi-autobiographical” novel Baby Driver (1981) last night. The writing immediately struck me as very bad, very overwritten, ostentatious and clumsy, but I kept going, charmed by the charmingly charming naivety of the novel, which is not a naive novel at all, which turns into a rough and ready sex and drug novel, or sex and drug autobiography, or autofiction. (My instinct is that this is an autobiography with a lot of whoppers.) Our heroine is on heroin pretty quick, then turning tricks, then on to other adventures. But there’s a glib smudging of purple prose over any would-be tragic contours. She likes it! She really likes it! At least I think.

And yes, J. Kerouac is J. Kerouac’s only (acknowledged) child, and yes, he pops in now and then, a jolly fibbing wino, the poseur some of us always pegged him for, maybe a better phrase-turner than lil Jan, but somehow I think less real.

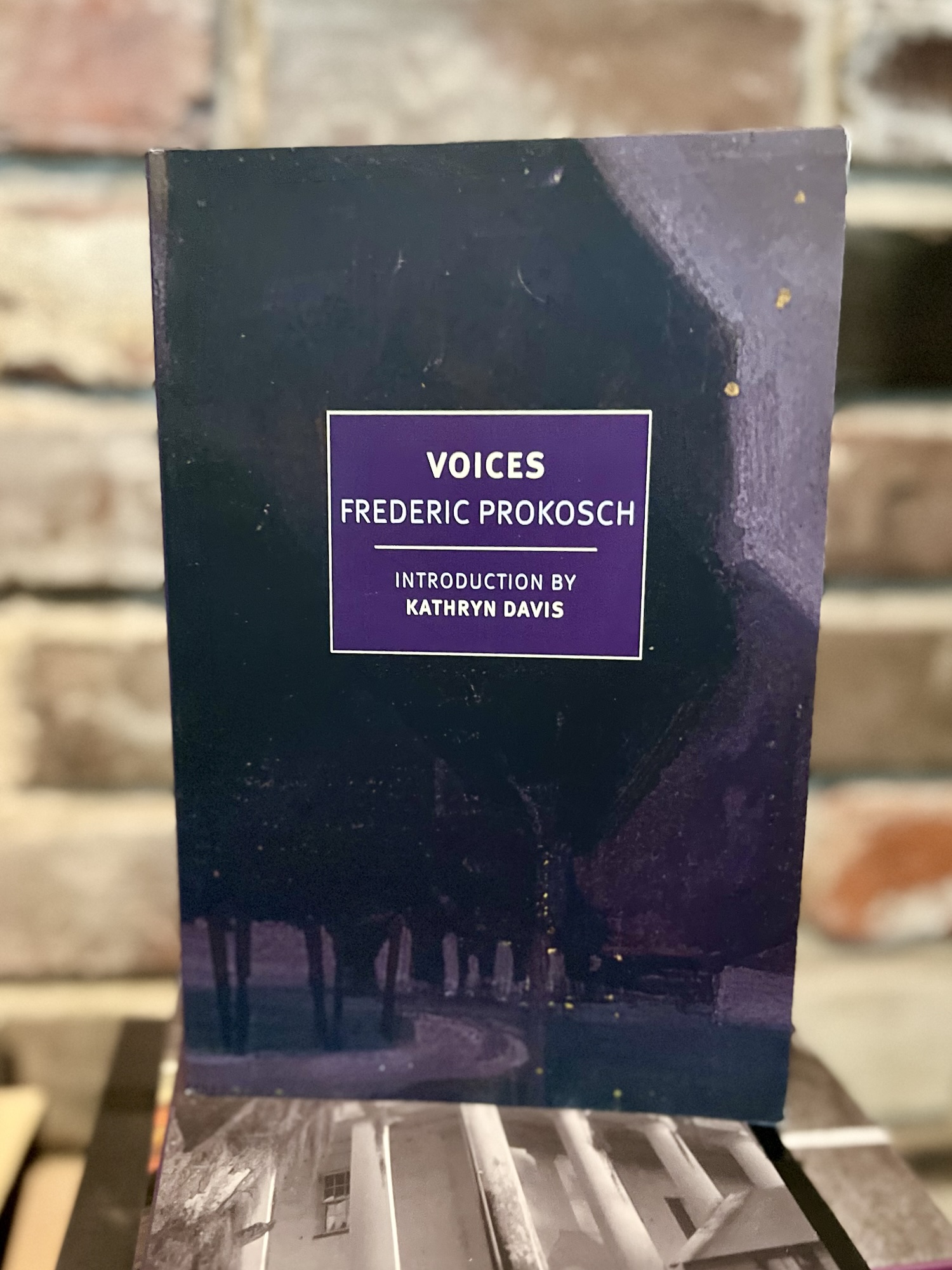

Frederic Prokosch’s 1982 memoir Voices is getting a reprint from NYRB. Their blurb:

Frederic Prokosch was a fantasist. His first novel, The Asiatics, was a stylish account of a man hitchhiking across an Asia that was more dream than reality. Praised by T. S. Eliot, Thomas Mann, and W. B. Yeats, it was a tremendous success, never to be replicated in Prokosch’s long career. In the 1940s, he moved to Europe, away from what he called the “middle-class and fancy dullness” of midcentury American letters, writing novels of a highly romantic kind, playing squash and tennis, collecting butterflies, and printing deluxe limited editions of poems he admired.

In 1982, Prokosch returned to the literary limelight with Voices—a self-proclaimed memoir framed by his childhood in Middle America and his old age in the South of France, made of short chapters about his encounters with famous figures, whose every word he seems to recall. Voices, too, is a work of fantasy. But if Prokosch’s portraits are not strictly true to life, they come alive as few portraits do. Whether he is playing tennis with Ezra Pound or retrieving Marc Chagall’s wallet from the Grand Canal, sharing a beer with Bertolt Brecht or a steam bath with W.H. Auden, Prokosch hypnotizes the reader with his ability to capture these artists’ cadences and characters, creating a masterpiece of imaginative memoir.

We first heard about Pasolini at university. I was going to Purchase, less than an hour from the city, and living in the country north of there. This was when you couldn’t dial up a movie on your laptop. Information was word of mouth and mysteries were rampant. You could only see movies like Pasolini’s at the Regency or the Thalia in Manhattan, or at one of the colleges with a film program. New York had plenty of them, but most were all the way the fuck up in Siberiaesque places like Binghamton or Rochester or worse. I forget which one Accattone was rumored to be playing at, but a bunch of us jammed in a VW Bug to go. We didn’t get far. Snow was falling, and between a funky heater and bald tires we had to turn back, dejected. But Harry was not to be denied. He said, “I got to see this movie.” He left with a baggie of cheap pot and a jug of even cheaper red wine stuffed in his shoulder bag. We watched through the windows as he walked into a blizzard toward the highway to hitch a ride hundreds of miles north.

I met Harry when we were teenagers. He lived nearby but went to a Catholic school, so it was the summers that I got the full dose. He had crazy long black hair and a scraggly, not-quite-there beard, and always wore cutoff jeans with combat boots, even in the winter. No one looked anything like him. He was also a chick magnet. They adored this maniac and he taught us why. He would preach the importance of buying flowers and presents, worshipping their birthdays, listening closely when they spoke.

A week later he showed up back at the house. He had made it there too late for the Accattone screening, but he tracked down the projectionist, asleep in his dorm room, and in exchange for the weed and the wine the guy took him back to the theater and ran the movie for him.

Harry acted out the whole film for us as we passed around joints and watched him impersonate Franco Citti and the rest of the young Roman street thugs. My passion for this person named Pier Paolo Pasolini was ignited, and when The Decameron, his latest film, came to 59th and Third Ave we raced down and got to see the master in action. Being Italian American is one thing, to see the real ones in their natural habitat was mind-blowing. The filmmaking loose, free-form, easy, the great Tonino Delli Colli’s miraculous mix of natural light with his own instruments catapulted you to another world. How the fuck do you do this? When we realized later on it was Pasolini himself playing Giotto’s pupil, that clinched it for me. Godard was my man, but now it was all things Pasolini. We devoured everything we could find about him, even met someone at film school who had assisted him for a summer who we tortured for information. Then, in 1975, he got killed. If he was a god before, he now entered another dimension of coolness. James Dean crashing his sports car, Morrison, Janis, and Hendrix all doping out was one thing, but getting run over by your own trick on some overgrown strip of beach past the Rome airport, that wins the prize.

When asked his occupation for a visa or other official documents he would just put down “Writer.” Writer, director, journalist, poet, political activist, that was the message. Directing films is only a part of it, not all of it.

The research for our movie brought me in touch with his most intimate friends and family. My screenwriter Maurizio Braucci and I heard the message over and over. Pasolini was a man of compassion and commitment, full of love. On the set he treated everyone with kindness, down to the youngest assistants.

Salò, his last feature, is so far outside the box it’s from another galaxy. We were at the American premiere up on 57th Street. It was a long movie so we came with wine and bread and cheese. There were fifteen people in the theater and when it ended there were eight. To this day I am still in contact with two of them because of that shared experience. We stood under the marquee and just looked at each other, no one saying a word. It was night now and it had begun to snow, but who cared, I didn’t even know what city I was in.

From Abel Ferrara’s 2025 memoir Scene.

Self-Portrait with Animal Bed, 2025 by Julie Heffernan (b. 1956)

“Each Person to Her Paradise”

by

Diane Williams

In the long run, as a sequel to our other less strenuous raptures, he undressed and put himself on the bed belly down—lying cross-ways across it.

This was his come hither. His arms were pressed against his sides, I think.

He was facedown, I think. Facedown, really? Like a swimmer. Were his arms really stretched out in front?

And the stress that ensued was not the strange thing.

I did my best, keeping my lower part centered when I met up with him—after he had moved his location and changed his posture accordingly.

I was awkwardly raising a leg, flexing a knee.

But this is my motto: While you can’t figure out how, you do it.

And I was wearing my skin unfresh and sallow and some sympathetic restoration in that regard is still called for.

But by the time he stuck his hand out toward me . . . Did he then?

So . . . no, neither of us accomplished anything particularly tender then or later.

He had a habit—how he took my arm, as if with a heavy pincers, on a subway platform to maneuver us if we were in a crowd—and I really enjoyed that aspect of our relation.

Each person to her paradise.

That grip of his, as a matter of fact, was, and still is, when I think of it, a source of inspiration—like a legend or wisdom—like humor can be.

When water gushed down his body when he rose from the tub, after he had bathed, that flow of water was a drumroll.

The god in this story is this man and I do not accuse him of anything. I could.In the long run, as a sequel to our other less strenuous raptures, he undressed and put himself on the bed belly down—lying cross-ways across it.

This was his come hither. His arms were pressed against his sides, I think.

He was facedown, I think. Facedown, really? Like a swimmer. Were his arms really stretched out in front?

And the stress that ensued was not the strange thing.

I did my best, keeping my lower part centered when I met up with him—after he had moved his location and changed his posture accordingly.

I was awkwardly raising a leg, flexing a knee.

But this is my motto: While you can’t figure out how, you do it.

And I was wearing my skin unfresh and sallow and some sympathetic restoration in that regard is still called for.

But by the time he stuck his hand out toward me . . . Did he then?

So . . . no, neither of us accomplished anything particularly tender then or later.

He had a habit—how he took my arm, as if with a heavy pincers, on a subway platform to maneuver us if we were in a crowd—and I really enjoyed that aspect of our relation.

Each person to her paradise.

That grip of his, as a matter of fact, was, and still is, when I think of it, a source of inspiration—like a legend or wisdom—like humor can be.

When water gushed down his body when he rose from the tub, after he had bathed, that flow of water was a drumroll.

The god in this story is this man and I do not accuse him of anything. I could.

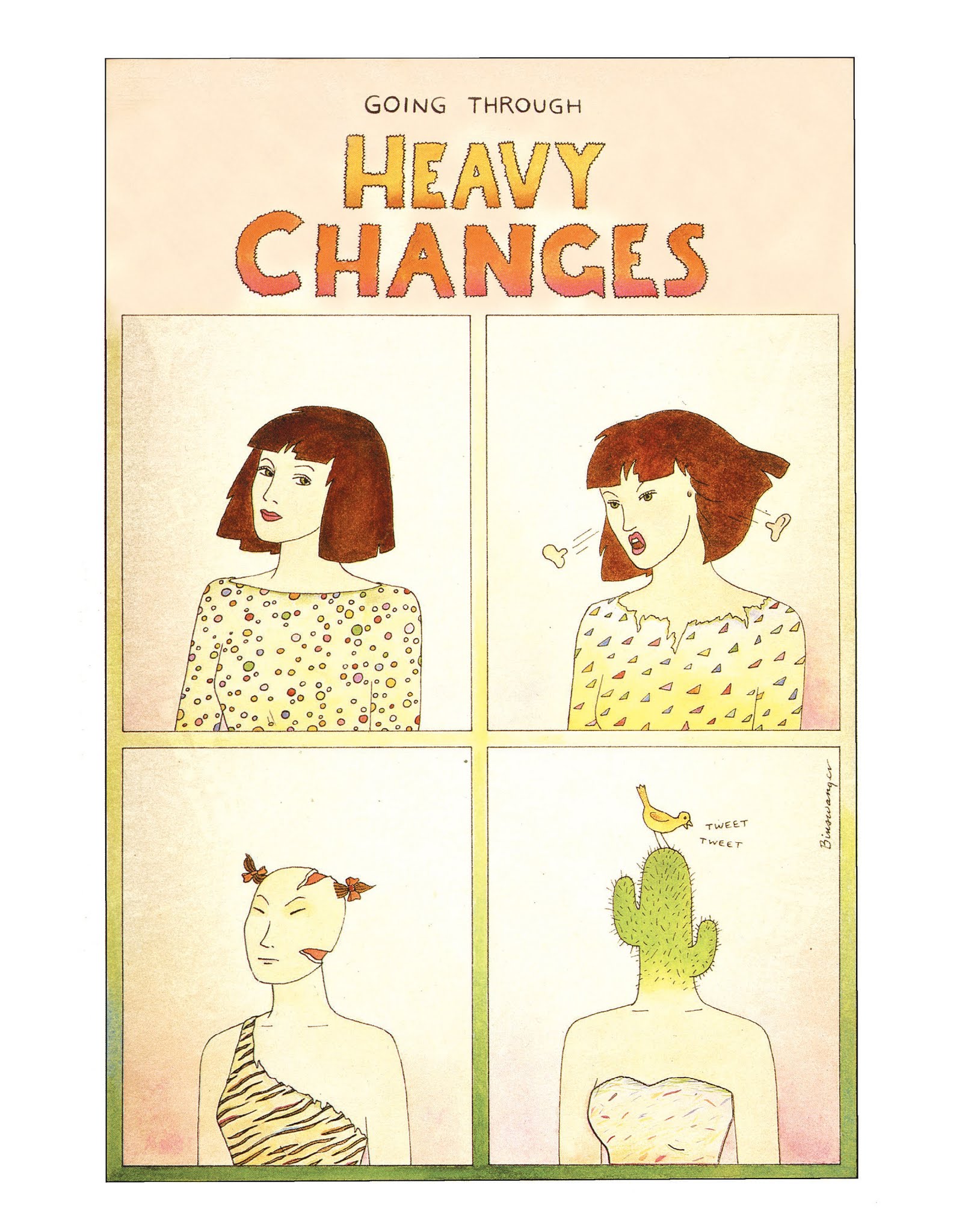

Back cover by Lee Binswanger for Wimmen’s Comix #12, November 1987, Renegade Press. Reprinted in The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Vol. 2, Fantagraphic Books.

“California”

by

David Berman

first published in Caliban #8, 1990

It’s a movie based on a true story,

it’s a fat boy on a train with a dollar,

it’s got no cavities

and God on its shoulder.

Red meat, white people and blue skies,

it’s 50 states stuck together with barbecue sauce.

If you’re poor, someone will cry for you.

A cup of water is free

and the slave population here is zero.

From Arizona’s desert drug factories

to the hot sidewalks of Little Rock

to Florida’s Jewish beaches

people feel good about themselves

and their bodies.

Of course it’s hard to forget the kids outside Pittsburgh

who are into sorcery and stuff,

and the crooked men and women of Nevada dreaming of crime

in their blackened houses.

But on Sunday, when balloons float above the stadium,

and the highways stretch like cats under the hot sun,

we drive to the pool knowing the wheels could fall off,

and even California loves its future ocean grave.

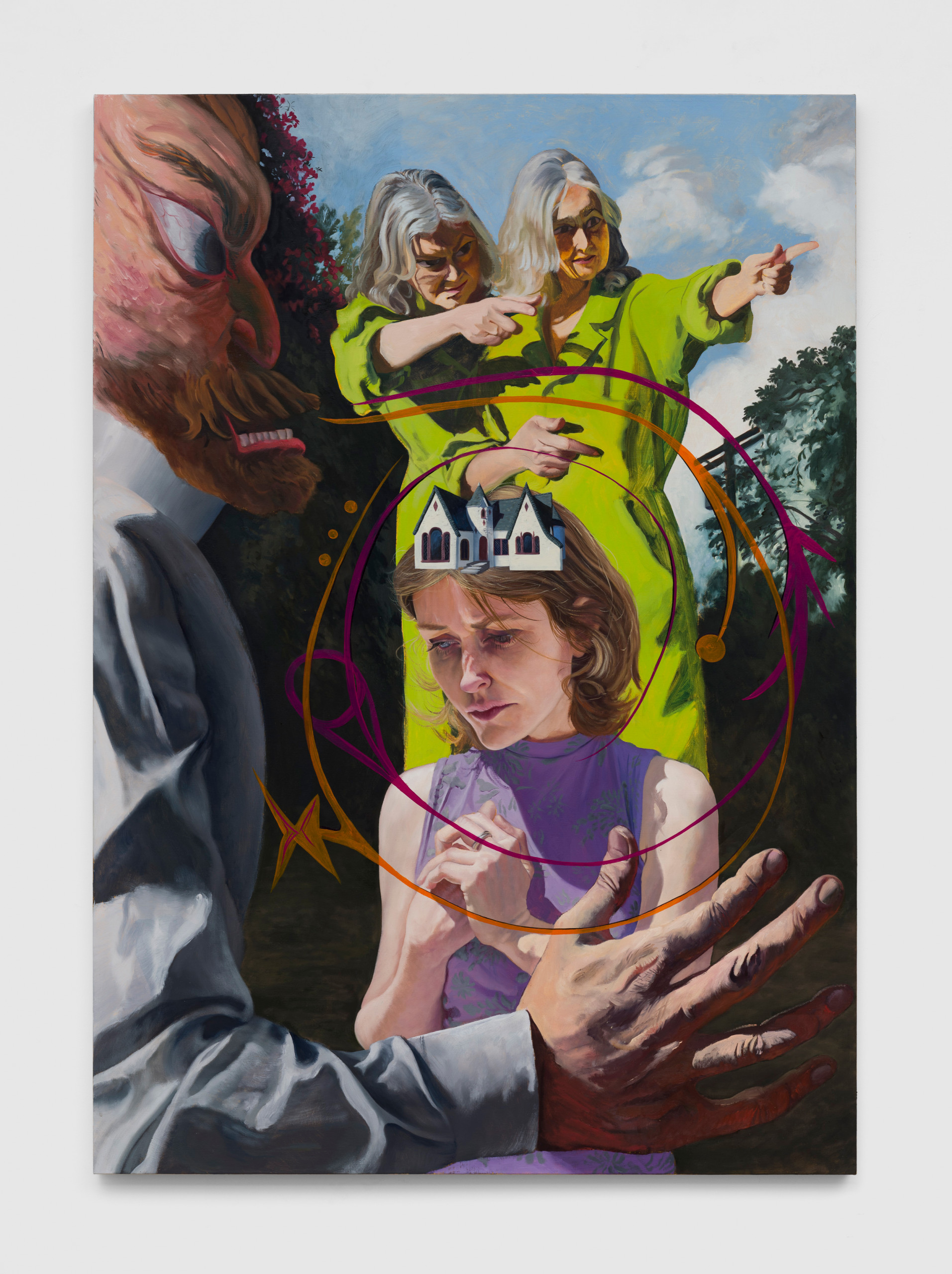

Trouble, 2022 by Justin John Greene (b. 1984)

I got a copy of the last (maybe latest?) of David Ohle’s Moldenke novels, The Death of a Character, in today’s mail. I’ve read or reread Ohle’s Moldenke’s novels over the past few weeks, and I think they are some of the best, grossest, funniest diagnoses of the emerging 21st-century apocalypse I’ve ever encountered. I’m a bit sad that The Death of a Character might be the last one, but there’s always rereading. I got a copy of Ohle’s 2014 short novel The Blast, which I think is a Moldenke novel without Moldenke. (Ohle’s 2008 novel The Pisstown Chaos is basically a Moldenke novel without Moldenke.)

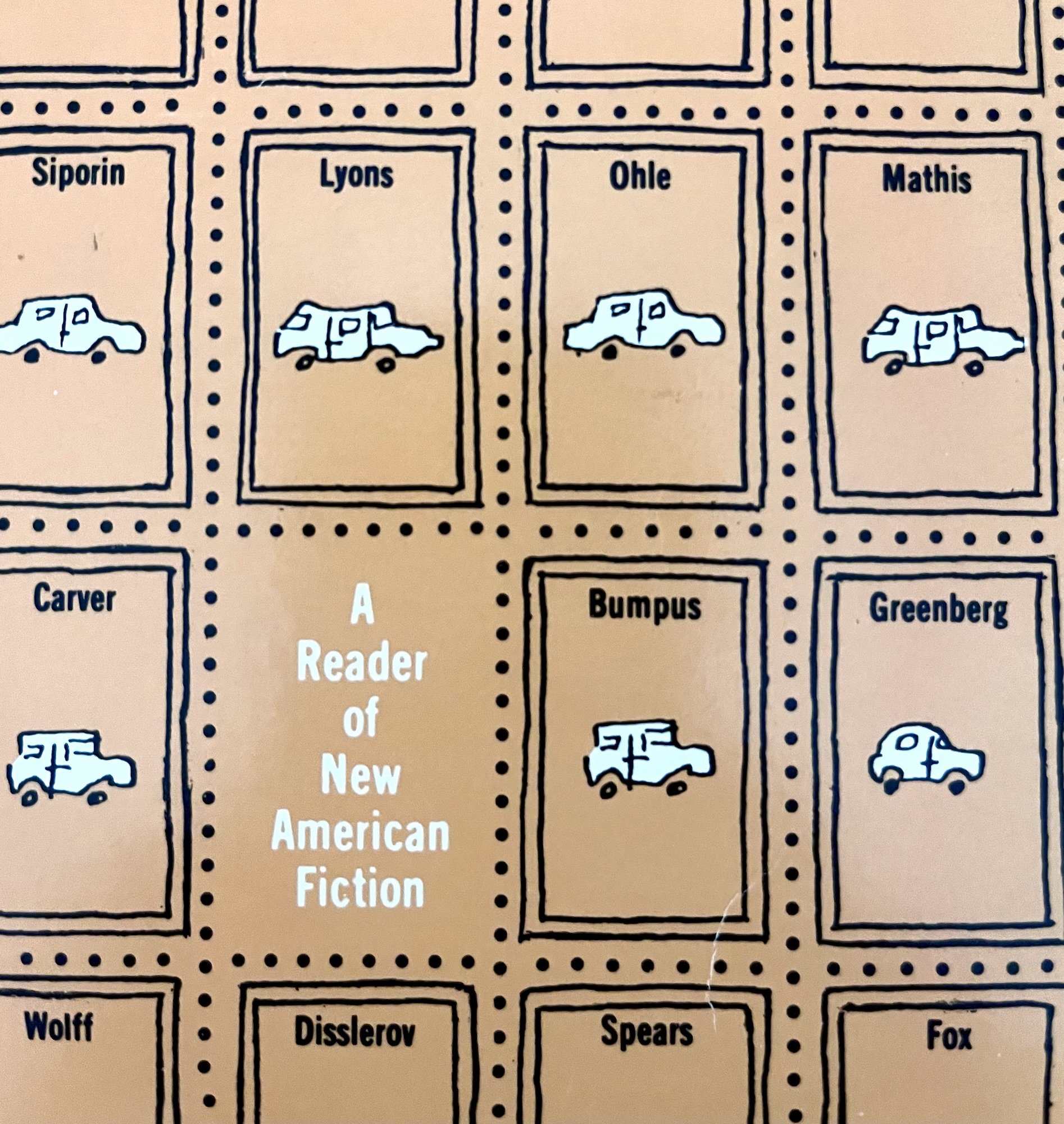

I also got a copy of a 1981 anthology called A Reader of New American Fiction which features a piece by David Ohle I’d never heard of before, called “Easy Neutronics.” I got the book via interlibrary loan, requesting it as part of an in-class demo I was doing during a class. It arrived bearing the stamp of Brevard Community College (née Brevard Junior College), which is now Eastern Florida State College. Thank you to the librarian in Titusville.

The book appears to have never been read.

“The Value of Not Understanding Everything”

by

Grace Paley

The difference between writers and critics is that in order to function in their trade, writers must live in the world, and critics, to survive in the world, must live in literature.

That’s why writers in their own work need have nothing to do with criticism, no matter on what level.

In fact, since seminars and discussions move forward a lot more cheerily if a couple of bald statements are made, I’ll make one: You can lunge off into an interesting and true career as a writer even if you’ve read nothing but the Holy Bible and the New York Daily News, but that is an absolute minimum (read them slowly).

Literary criticism always ought to be of great interest to the historian, the moralist, the philosopher, which is sometimes me. Also to the reader—me again—the critic comes as a journalist. If it happens to be the right decade, he may even bring great news.

As a reader, I liked reading Wright Morris’s The Territory Ahead. But if I—the writer—should pay too much attention to him, I would have to think an awful lot about the Mississippi River. I’d have to get my mind off New York. I always think of New York. I often think of Chicago, San Francisco. Once in a while Atlanta. But I never think about the Mississippi, except to notice that its big, muddy foot is in New Orleans, from whence all New York singing comes. Documentaries aside, my notions of music came by plane.

As far as the artist is concerned, all the critic can ever do is make him or break him. He can slip him into new schools, waterlog him in old ones. He can discover him, ignore him, rediscover him … Continue reading ““The Value of Not Understanding Everything” — Grace Paley”