Fourteen-year-old Preston Wildey-King has a lot of problems. He’s on the outs with his girlfriend Peggy. His best friend Ryan always leers at him in a funny way, and Ryan’s older brothers want him to join their gang and do crimes. His older sister Erica accuses him of stealing from her. Preston’s failing at math, and his teacher might be trying to seduce him. His mother doesn’t know what to do with him.

And he’s addicted to Pepsi Cola.

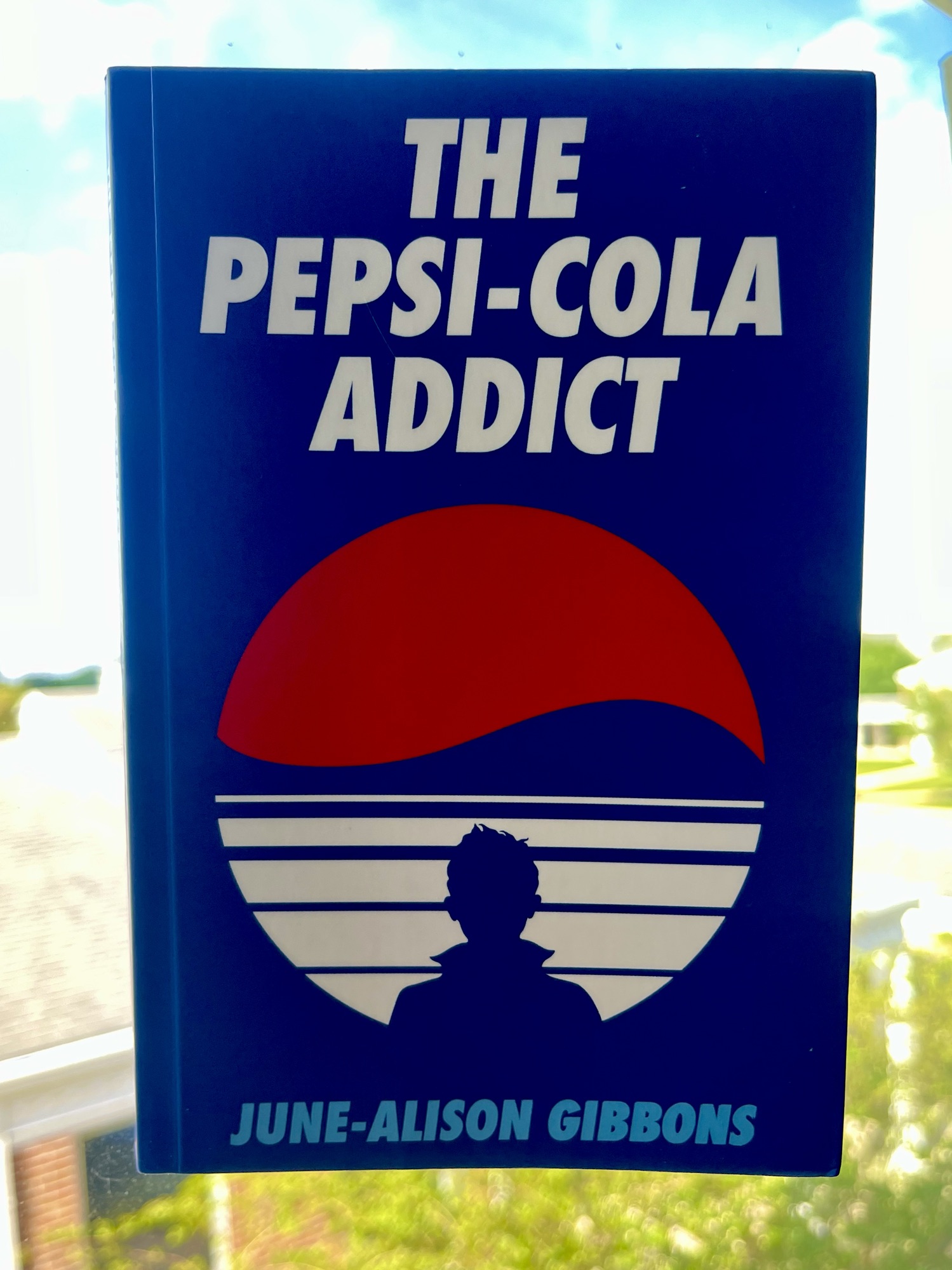

This is, roughly, the premise of June-Alison Gibbons’ 1981 novel The Pepsi-Cola Addict, a raw and distressing young-adult novel that was actually written by a young adult. Gibbons was just sixteen-years-old when she wrote The Pepsi-Cola Addict and pooled her dole money with her twin sister Jennifer to have it published by a vanity press. Two years later, after a spree of petty crimes and then more serious crimes culminating in arson, Gibbons and her sister were committed to a psychiatric hospital and confined there for over a decade. The Gibbons twins’ story was detailed in a book by journalist Marjorie Wallace called The Silent Twins, later followed by a television documentary; in 2022, Wallace’s book was adapted into a feature film of the same name.

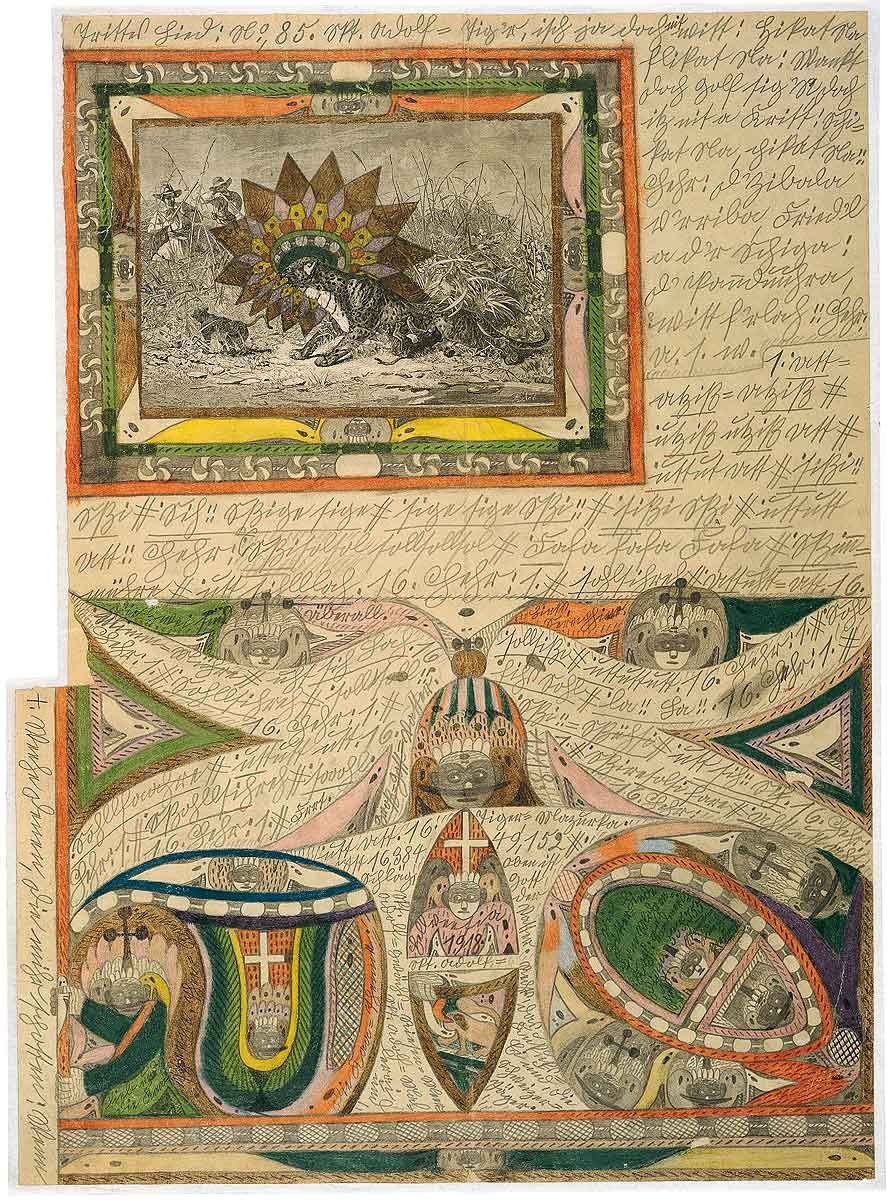

I knew nothing of the Gibbons’ sad early life when I picked up The Pepsi-Cola Addict at an indie bookstore, intrigued by the goofy title and bright pop art cover. The jacket copy informed me briefly of the Gibbon twins’ incarceration in Broadmoor psychiatric hospital and called the novel “one of the great works of twentieth-century outsider literature,” but I restrained myself from further exploring the author’s biography until after I’d read her novel (I’d recommend you do the same, reader).

It is difficult to explain how unnerving the world of The Pepsi-Cola Addict is. Gibbons grew up in Wales, the daughter of Barbadian immigrants, but she sets her novel in a version of Malibu Beach the creation of which seems informed primarily by picture postcards and pure fantasy. Preston lives in a shabby apartment in Malibu with his mother and sister. This ratty apartment is across from the beach, where he often wanders at night. He attends something called MALIBU STATE SCHOOL, which (contrary to U.S. school customs) runs year round, even in the (contrary to coastal California meteorological customs) sweltering summer heat.

Everything is more-than-slightly off in Gibbons’ setting. She anchors the plot in realistic visual detail, but the events, mediated via Preston’s bewildered consciousness, can’t square with their own apparent reality. The effect reminds one of the sinister dread the films of David Lynch often evoke from the most mundane of images—a lawn sprinkler, a Dumpster—or the fiction of Roberto Bolaño, which so frequently gnaws at the reader’s stomach, anxiously assuring him that everything could go to shit at any moment.

There’s a grittiness to Gibbons’ version of “Malibu” that belies its pop art contours, an essential griminess that finds its most repeated expression in Preston’s constantly sweating. Our hero sweats and sweats some more. And why shouldn’t he? Preston might be confronted with radical violence or unwanted sexual encounters at any time, and even if it’s not the twin axis of sex and violence coming at him, he’s always in danger of t misinterpret the language, faces, and intentions of every single person he interacts with. But he sweats nonetheless, addict that he is.

I haven’t really touched on Preston’s Pepsi addiction, although it’s definitely a problem, although no one can quite say why it’s a problem. (And, to be clear, he’s addicted to Pepsi, not Coca-Cola, as he makes very clear to Peggy during a date gone wrong (she tries to bring him a Coke)). Girlfriend Peggy has already left Preston once before because of his addiction. Preston’s sister Erica beats him up over the apparent theft of a five-dollar bill she’d saved, which she’s convinced he’s used to buy Pepsi. Preston’s mother is concerned that the Pepsi addiction prevents her boy from his studies—and indeed, he does skip class to surreptitiously sip the sweet nectar from a can he’s hidden in his gym locker.

The novel’s opening scene depicts Preston buying Pepsi in bulk, openly at a grocery store, during daylight, but as the story progresses, his purchases become more coded in furtive anxiety and sexual confusion. Consider this night scene, where a young liquor store clerk looks “somewhat lasciviously” at Preston while he purchases his cans:

He took three cans of pepsi and walked directly toward her. She looked about twenty; her large blue eyes seemed prominent from the rest of her face. Her white pinafore dress strained across her breasts as she turned to calculate money on the large till.

Preston glanced at her hands. Finding no ring on her finger, he looked closer at her. She looked back at him.

“That’ll be one dollar, two nickels please.” Feeling the touch of her hand as he handed her the money, Preston felt a quiver pass through him. He looked intently into her eyes, his excited passion aroused as he sensed a new look come about her. Immediately a hardening pain hit him between his eyes. Preston detached himself from his trance. Hot, speechless he turned and went through the open door, carrying his cans awkwardly.

By the novel’s climax, Preston’s craving for the soda has crossed into criminal territory. He helps a gang ransack a store, but only has eyes for the fizzy dark stuff:

He watched as they pulled down the shelves, scattering food onto the floor. He watched as they raided the store tills, pushing money into their pockets. Preston glanced around nervously. His eyes rested on a familiar stack standing in the corner of the store. With one move of his body Preston was over there, fighting desperately to free them from the cardboard box. His eyes dilated; he ripped off the ring, tilting the can to his lips, as the liquid ran down his chin. The pepsi cola, cool and tingling, entered his throat, like the spray of a fireman’s hose, killing the hotness of the fire.

Have I spoiled the plot’s trajectory by sharing that Preston takes part in the gang’s crime? I don’t think so. The Pepsi-Cola Addict is a picaresque novel, sure, but it also, perhaps paradoxically to the claim I made just a few words before, has clear, linear, and somewhat tragic plot.

And that plot—well, look, I have no idea whether or not Gibbons had read S.E. Hinton’s 1967 novel The Outsiders, a seminal work of American (so-called) “young adult” fiction—but it is the book that, at least in my narrow estimation, The Pepsi-Cola Addict has the most in common with. Like Hinton, Gibbons captures the ever-present anxiety of being a teenager, that time of amorphous body and amorphous mind, that time we find ourselves an outsider among outsiders. And like Hinton, Gibbons was also a teenager writing about teenagers—again, this is truly a “young adult” novel, and to read it is to be thrust into an alienating and alienated consciousness.

It is likely though that we do not immediately think of S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders as the work of an “outsider artist,” although she likely fits the loosest definitions of that term. (The term’s originator, Roger Cardinal, didn’t really think much of the term; he wanted to use Art Brut for his book’s title, but the publisher made him go with something more “English.”) But The Outsiders was and remains controversial and still faces challenges in school libraries, even if its apparent grittiness has since been synthesized and integrated into the confines of the YA genre proper. In contrast, The Pepsi-Cola Addict truly is “outsider” (even if its author took a correspondence writing course)—the general vibe is closer to a Paul Morrissey or early John Waters film than it is the gentle realism of Francis Ford Coppola. Like Hinton’s teens, Gibbons’ adolescents have their own argot, but it is bewildering at times. Characters call frequently call each other “babe,” for example, no matter if their relationship warrants it or not. At one point, his sister demands to know where he got the “roorback” on her. Has any teen—any person, really—used the term “roorback” in slang?

I’ve neglected so much in this short book—Preston’s confused sexual/nonsexual relationships with his best friend Ryan and his teacher Ms. Rosenberg, in particular, are central to the themes of the book, and will no doubt be of great interest to many readers. I might also have made the book sound befuddling and unattractive, when, to be clear, I fucking loved it—The Pepsi-Cola Addict is odd and distressing, yes, but it’s also very well-written, somehow simultaneously naïve and sophisticated, raw and refined, resoundingly truthful and plainly artificial. It’s full of strange little flickers, images that creep into Preston’s view, never to be explored or explained, simply witnessed in a kind of anxious low-level terror. And while I’ve compared The Pepsi-Cola Addict to The Outsiders, the feeling of reading the book is much closer to, say, Ann Quin’s Berg or João Gilberto Noll’s Quiet Creature on the Corner or Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School. Obviously, this book Not For Everyone, but I think it will appeal to readers who enjoy a certain queasy, semi-surreal flavor. Finally, I think the novel can and should be enjoyed outside of any lurid interrogation of its author’s mental health and unusual background. Undoubtedly, there will be some readers drawn to Gibbons’ novel by the various Silent Twins stories out there—the film, the documentary, the book…but, to be clear, The Pepsi-Cola Addict is a strange and unsettling tale of teen angst that stands on its own as a small burning testament of adolescent creativity unspoiled by any intrusive “adult” editorial hand. Recommended.

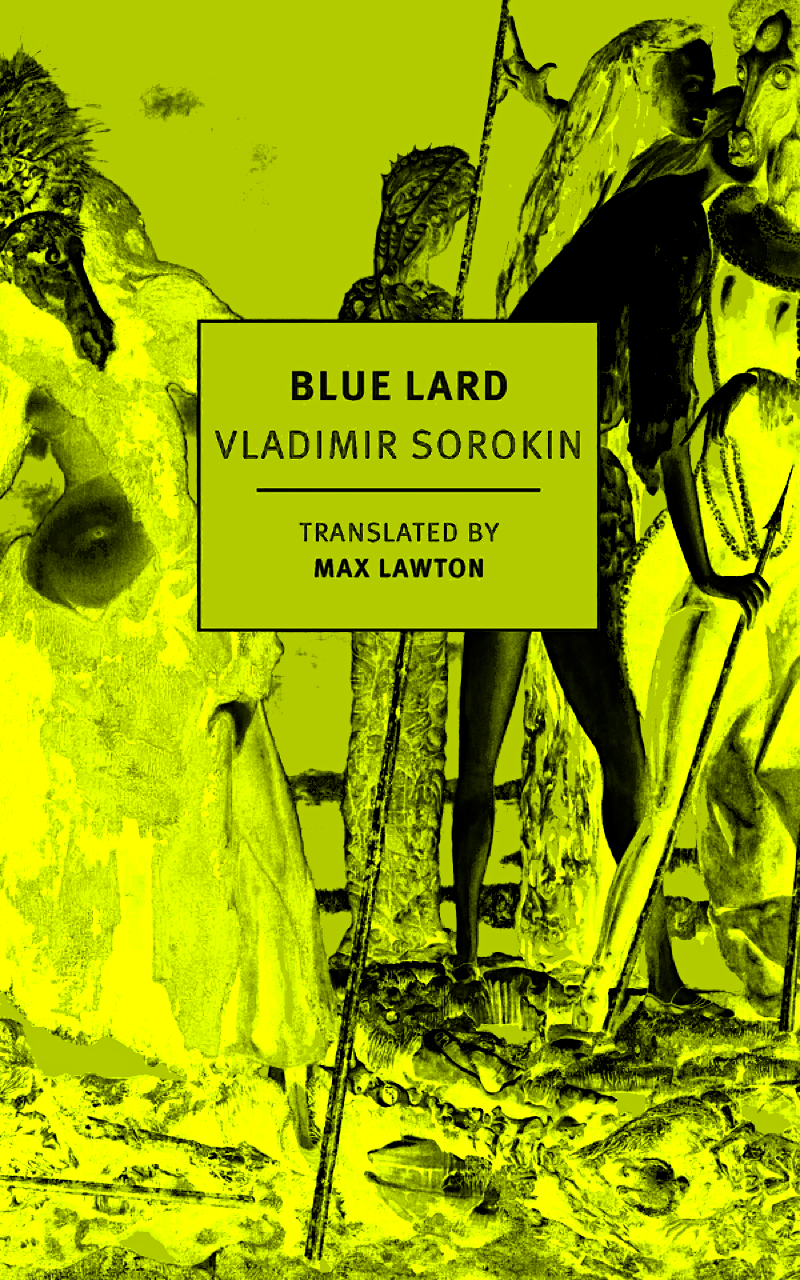

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…