RIP John Barth, 1930-2024

John Barth died yesterday at the age of 93. Between 1956 and 2011, he published thirteen novels and four short story collections. He also published a quartet of nonfiction books—his “Friday” books—that collected the many essays, introductions, lectures, and other pieces he wrote in his life time. The title of the last collection of nonfiction, 2022’s Postscripts (or Just Desserts): Some Final Scribblings, consciously pointed to the end of his road.

Barth will most likely be remembered for the novels and stories he published in the 1960s and 1970s, when he began practicing the metaficitonal arts. Critics and reviewers have alternately accused Barth of being a fabulist, an anti-novelist, a black humorist, a goddamn nihilist (or at least a creator of nihilist fiction), but most predominately, as a postmodernist.

Barth’s run from 1960-1972 is particularly impressive: The Sot-Weed Factor, Giles Goat-Boy, Lost in the Funhouse, and Chimera. In these works, Barth helped to create a new postmodernist tradition in U.S. fiction. Like most postmodern practitioners of his era, he was ambivalent and perhaps suspicious of the term postmodern. But Barth’s 1967 essay “The Literature of Exhaustion”, oft-cited as a postmodernist manifesto, called for a new literature in the face of “the used-upness of certain forms or exhaustion of certain possibilities,” which he cheerfully noted was “by no means necessarily a cause for despair.” (It’s a fine read, but not really a manifesto so much as a love letter to his hero Jorge Luis Borges.)

Many readers have interpreted “The Literature of Exhaustion” as a rebuke to realist fiction; Barth’s first two novels, The Floating Opera (1956) and The End of the Road (1958) are thus surprisingly realistic, at least for the reader who finds himself coming to them after, say, the metafictional fireworks of Lost in the Funhouse or Chimera (that reader was me, reader). 1960’s The Sot-Weed Factor marked a massive shift for Barth–in tone, complexity, structure, themes, and, quite frankly, length.

Interestingly, Barth claimed in his introduction to the 1987 reprint of Giles Goat-Boy that he regarded his first three novels “as a loose trilogy,” noting that in producing The Sot-Weed Factor,

I had put something behind me and moved into new narrative country. Just what that movement was, I couldn’t quite have said; today it might be described as the passage made by a number of American writers from the Black Humor of the Fifties to the Fabulism of the Sixties. For four years, writing Sot-Weed, I’d been more or less immersed in the sometimes fantastical documents of U.S. colonial history: in the origins of “America,” including the origins of our literature. This immersion, together with the suggestion by some literary critics that that novel was a reorchestration of the ancient myth of the Wandering Hero, led me to reexamine that myth closely: the origins not of a particular culture but of culture itself; not of a particular literature, but of the very notion of narrative adventure, especially adventure of a transcendental, life-changing and culture-changing sort.

Barth above offers a concise description of the trajectory of the next few decades of his writing.

In my memory, I’m most fond of The Sot-Weed Factor, a sprawling satire of American colonialism and storytelling itself, simultaneously rich and bloated. In my memory, I think of it as a companion to and forerunner of Pynchon’s masterpiece Mason & Dixon. Revisiting my review earlier today—composed nearly thirteen years ago—I see that I was quite unkind to the novel at times, describing it at one point as “the literary equivalent of a very bright writer jacking off to his own research.” Ah well. I was no doubt exhausted by the assy-turvy thing’s 800 pages.

Giles Goat-Boy (1966) is also very long—Barth would go on to write many long novels—and I think it’s probably the consensus favorite of Barth acolytes. Barth described Giles Goat-Boy as “the adventures of a young man sired by a giant computer upon a hapless but compliant librarian and raised in the experimental goat-barns of a universal university, divided ideologically into East and West Campuses.” Like The Sot-Weed Factor, Giles Goat-Boy is a parodic picaresque of displaced identity. It’s in Giles Goat-Boy that Barth begins his life-long practice of metafiction.

Barth’s metafiction evinces in more bite-sized doses in the collection Lost in the Funhouse (1966). This was the first Barth I read, sometime in the 1990s, and I suspect many readers found their way to it the same way I did, via David Foster Wallace; specifically, through Wallace’s novella Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, an intertextual response to Funhouse. Lost in the Funhouse is the perfect starting place for anyone interested in Barth’s metafictional postmodernism (and it might also be the last stop for some readers).

I think the next one I read was Chimera (1972), a book that daunted me so much when I was younger that I broke into sweats reading it. Revisiting a few years ago I found it far funnier, sillier, and comprehensible than I would have thought. At the outset of Chimera, Barth inserts himself as a somewhat-feckless genie who appears before Scheherazade and Dunyazade and, in a wonderful time-loop conceit, gives Scheherazade the “1001 Nights” gambit of story-telling-as-a-method-to-stave-off-rape-and-murder. Barth inserts himself into a frame tale around a frame tale around a frame tale. A reread of Chimera’s initial frame tale reveals realistic autofictional tinges into Barth’s metafictional gambit. The Genie–Barth–laments that “At one time…people in his country had been fond of reading; currently, however, the only readers of artful fiction were critics, other writers, and unwilling students who, left to themselves, preferred music and pictures to words.” Barth’s Genie has writer’s block, but he’s unsure “if his difficulty might be owing to his own limitations, his age and stage and personal vicissitudes; how much to the general decline of letters in his time and place; and how much to the other crises with which his country (and, so he alleged, the very species) was beset.” Modernist existential despair was never really exhausted, right? It just found new forms.

I’ll admit that I didn’t read much of Barth’s post-1970’s work, aside from the occasional essay or short story. I didn’t make any kind of dent into the near-800 pages 1979’s LETTERS (in fairness, I find even short epistolary novels tedious), and the last one I took a crack at was 1987’s The Tidewater Tales, making it somewhere farther into its near-700 pages before turning my poor attention elsewhere.

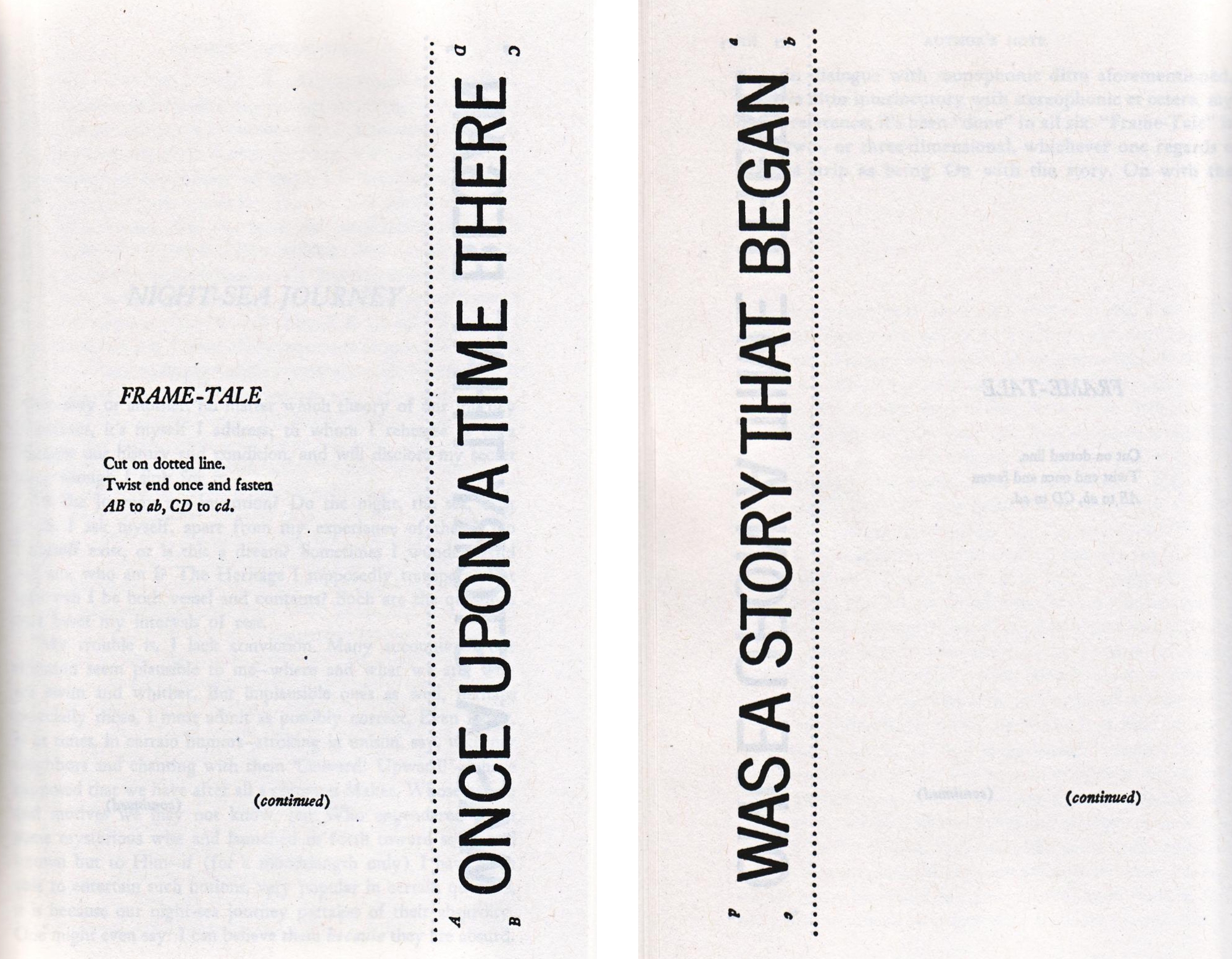

Like many readers, Barth’s 1960s and 1970s was a gateway drug for me to postmodernist writers like William Gaddis, Thomas Pynchon, William Gass, and Robert Coover. Most of that generation of American postmodernists are gone, but I like to think that their stories will go on. I’ll leave it with the opening piece from Lost in the Funhouse, “Frame-Tale.” The story never ends.

From Michael Thomas Hudgens’s Donald Barthelme, Postmodernist American Writer

From Michael Thomas Hudgens’s Donald Barthelme, Postmodernist American Writer