Q: You don’t consciously see yourself as John Barth, the postmodernist?

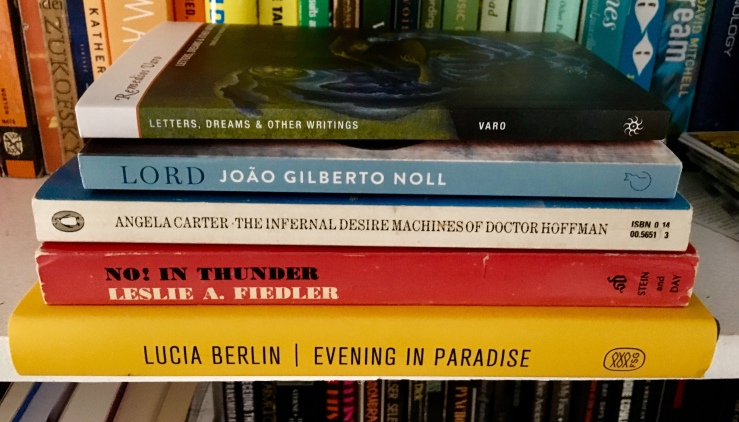

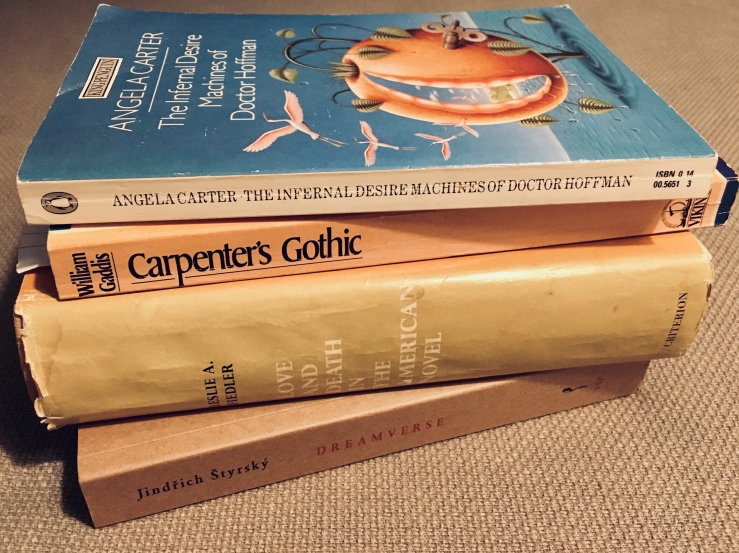

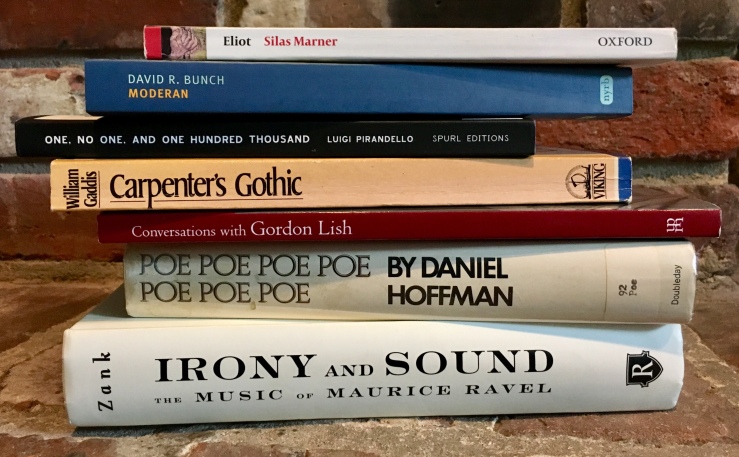

JOHN BARTH: Oh no, no, and the term now has become so stretched out of shape. I did a good deal of reading on the subject for a postmodernist conference in Stuttgart back in 1991, and I think I had a fairly solid grasp of the term then. At the time, there seemed to be a general agreement that, whatever postmodernism was, it was made in America and studied in Europe. At my end, I would say the definitions advanced by such European intellectuals as Jean Baudrillard and Jean- Francois Lyotard have only a kind of a grand overlap with what I think I mean when I am talking about it.g about it. They apply the term to disciplines and fields other than art-their thoughts about postmodern science, for instance, are very interesting-but when the subject is postmodern American fiction, things get murkier. So often we’re told, “You know, it’s Coover, Pynchon, Barth, and Barthelme,” but that’s just pointing at writers. Perhaps that’s all you can do. It led me to say once, “If postmodern is what I am, then postmodernism is whatever I do.” You get a bit wary about these terms. When The Floating Opera came out, Leslie Fiedler called it “provincial American existentialism.” With End of the Road, I was most often described as a black humorist, and with The Sot-Weed Factor, Giles Goat-Boy, and Lost in the Funhouse, I became a fabulist. Bill Gass resists the term “postmodernist,” and I understand his resistance. But we need common words to talk about anything. “Impressionism” is a very useful term which helps describe the achievements of a number of important artists. But when you begin to look at individual impressionist painters, the term becomes less meaningful. You find yourself contemplating a group of artists who probably have as many differences as similarities. I recall a wonderful old philosophy professor of mine who used to talk about the difference between the synthetic temperament and the analytical temperament. With the synthetic, the similarities between things are more impressive than the differences; with the analytical, the differences are more impressive than the similarities. We need them both; you can’t do without either. In that context, once you’ve come up with some criteria that describe what has been going on in a certain type of fiction composed during the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties, I think the differences among Donald Barthelme, Angela Carter, and Italo Calvino are probably more interesting than the similarities.

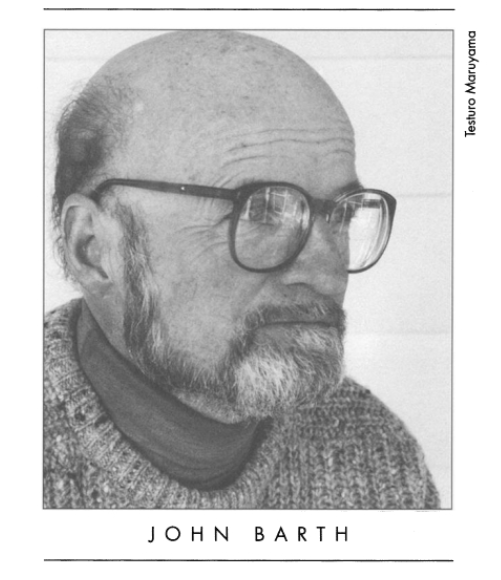

From an interview with Barth conducted by Charlie Reilly in the journal Contemporary Literature, Vol. 41, No. 4 (Winter, 2000).