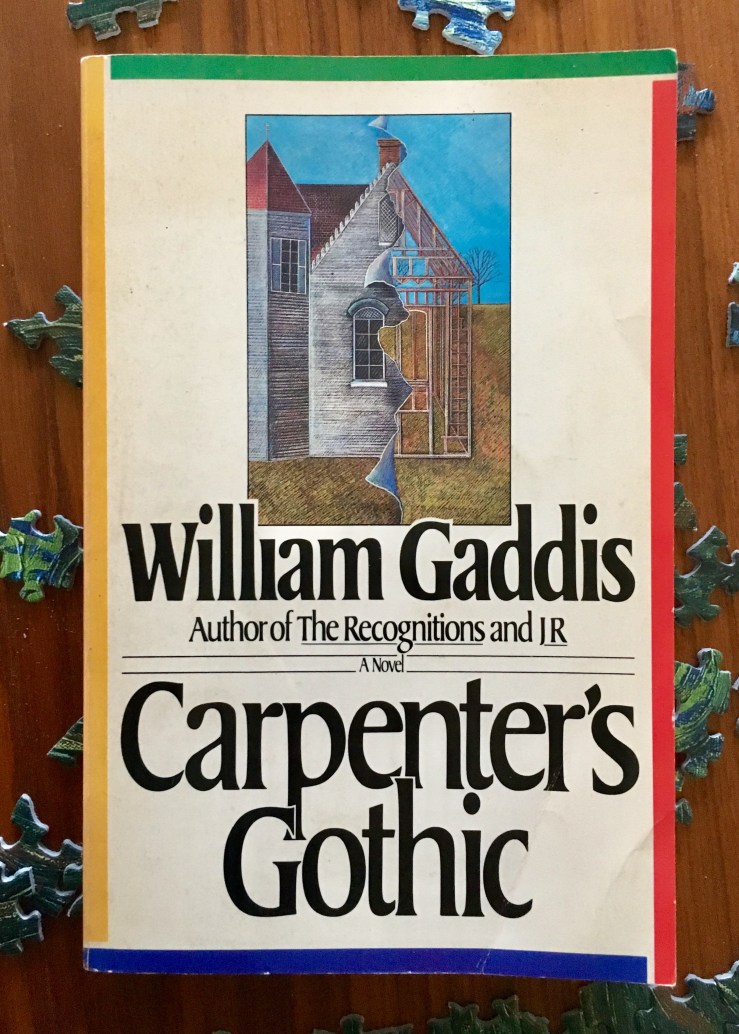

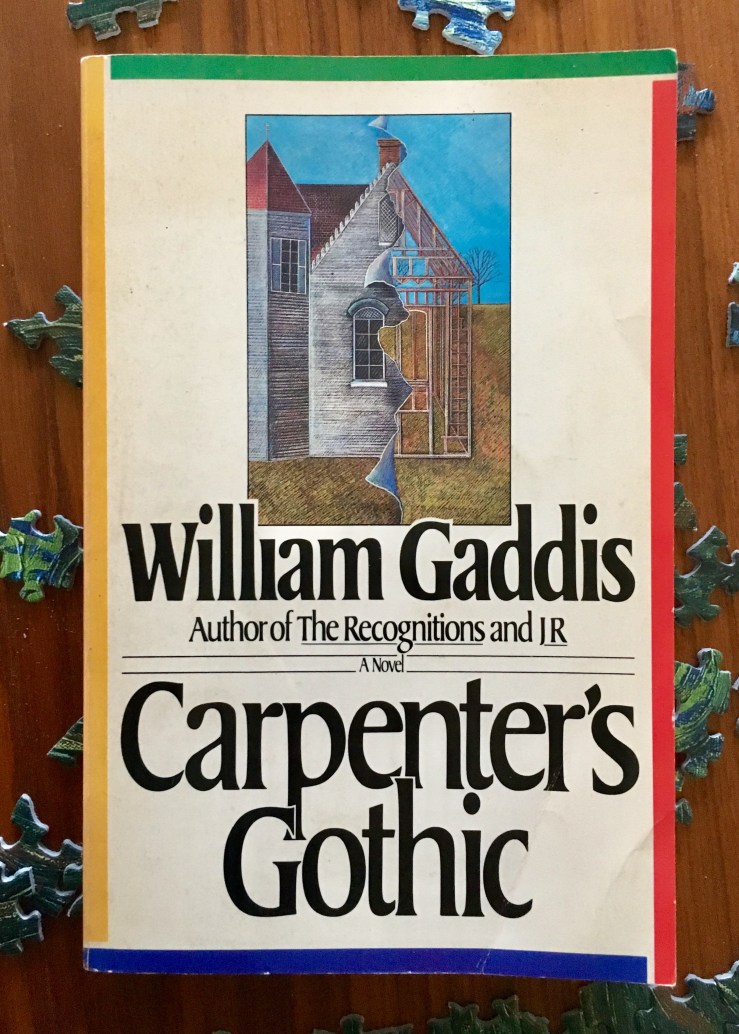

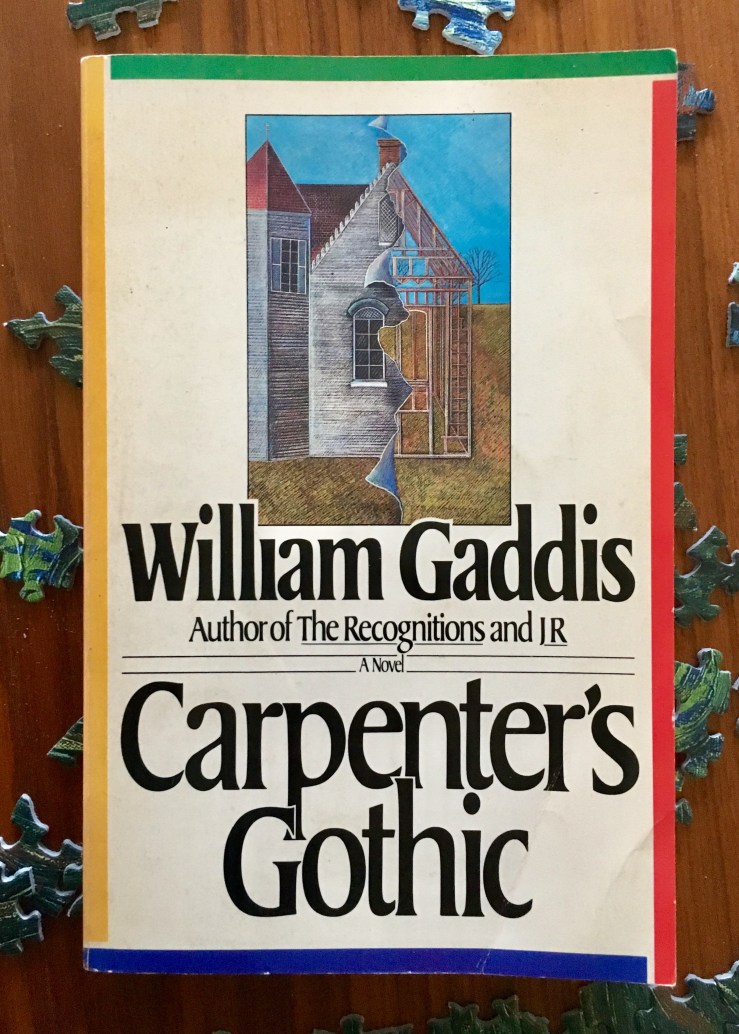

William Gaddis’s contribution to a 6 June 1982 New York Times article asking numerous authors what their next book will be. I suppose that Carpenter’s Gothic, being a Gothic, is a romance.

William Gaddis’s contribution to a 6 June 1982 New York Times article asking numerous authors what their next book will be. I suppose that Carpenter’s Gothic, being a Gothic, is a romance.

The fourth of seven unnumbered chapters in William Gaddis’s Carpenter’s Gothic is set over the course of Halloween, moving from morning, into afternoon, and then night. Halloween is an appropriately Gothic setting for the midpoint of Gaddis’s postmodern Gothic novel, and there are some fascinating turns in this central chapter.

A summary with spoilers is not necessary here. Suffice to say that our heroine Elizabeth Booth is left alone on Halloween in the dilapidated Rural Gothic style house she and her awful husband Paul rent from mysterious Mr. McCandless. As Paul exits the house to go on one his many fruitless business trips, he notices that some neighborhood kids have already played their Halloween tricks:

He had the front door open but he stood there, looking out, looking up, —little bastards look at that, not even Halloween till tonight but they couldn’t wait… Toilet paper hung in disconsolate streamers from the telephone lines, arched and drooped in the bared maple branches reaching over the windows of the frame garage beyond the fence palings where shaving cream spelled fuck. —Look keep the doors locked, did this last night Christ knows what you’re in for tonight… and the weight of his hand fell away from her shoulder, —Liz? just try and be patient? and he pulled the door hard enough for the snap of the lock to startle her less with threats locked out than herself locked in, to leave her steadying a hand on the newel…

The kids’ Halloween antics take on a particularly sinister aspect here, set against the stark New England background Gaddis conjures. We get gloomy streamers, desolate trees, and the bald, ugly signification of one lone word: fuck. (Fuck and its iterations, along with Gaddis’s old favorite God damn, are bywords in Carpenter’s Gothic). Paul’s reading of this scene is also sinister; he underscores the Gothic motif in telling Elizabeth to “keep the doors locked” because she doesn’t know what she’s “in for tonight.” Tellingly, the aural snap of Paul’s exit shows us that Elizabeth is ultimately more paranoid about being locked in. Indeed, by the middle of the novel, we see her increasingly trapped in her (haunted) house. The staircase newel, an image that Gaddis uses repeatedly in the novel, becomes her literal support. Elizabeth spends the rest of the morning avoiding chores before eventually vomiting and taking a nap.

Then, Gaddis propels us forward a few hours with two remarkable paragraphs (or, I should say, two paragraphs upon which I wish to remark). Here is the first post-nap paragraph:

She woke abruptly to a black rage of crows in the heights of those limbs rising over the road below and lay still, the rise and fall of her breath a bare echo of the light and shadow stirred through the bedroom by winds flurrying the limbs out there till she turned sharply for the phone and dialed slowly for the time, up handling herself with the same fragile care to search the mirror, search the world outside from the commotion in the trees on down the road to the straggle of boys faces streaked with blacking and this one, that one in an oversize hat, sharing kicks and punches up the hill where in one anxious glimpse the mailman turned the corner and was gone.

What a fantastic sentence. Gaddis’s prose here reverberates with sinister force, capturing (and to an extent, replicating) Elizabeth’s disorientation. Dreadful crows and flittering shadows shake Elizabeth, and searching for stability she telephones for the time. (If you are a young person perhaps bewildered by this detail: This is something we used to do. We used to call a number for the time. Like, the time of day. You can actually still do this. Call the US Naval Observatory at 202-762-1069 if you’re curious what this aesthetic experience is like). The house’s only clock is broken, further alienating Elizabeth from any sense of normalcy. In a mode of “fragile care,” anxious Elizabeth glances in the mirror, another Gothic symbol that repeats throughout this chapter. She then spies the “straggle of boys” (a neat parallel to the “black rage of crows” at the sentence’s beginning) already dressed up in horrorshow gear for mischief night and rumbling with violence. The mailman—another connection to the outside world, to some kind of external and steadying authority—simply disappears.

Here is the next paragraph:

Through the festoons drifting gently from the wires and branches a crow dropped like shot, and another, stabbing at a squirrel crushed on the road there, vaunting black wings and taking to them as a car bore down, as a boy rushed the road right down to the mailbox in the whirl of yellowed rust spotted leaves, shouts and laughter behind the fence palings, pieces of pumpkin flung through the air and the crows came back all fierce alarm, stabbing and tearing, bridling at movement anywhere till finally, when she came out to the mailbox, stillness enveloped her reaching it at arm’s length and pulling it open. It looked empty; but then there came sounds of hoarded laughter behind the fence palings and she was standing there holding the page, staring at the picture of a blonde bared to the margin, a full tumid penis squeezed stiff in her hand and pink as the tip of her tongue drawing the beading at its engorged head off in a fine thread. For that moment the blonde’s eyes, turned to her in forthright complicity, held her in their steady stare; then her tremble was lost in a turn to be plainly seen crumpling it, going back in and dropping it crumpled on the kitchen table.

The paragraph begins with the Gothic violence of the crows “stabbing and tearing” at a squirrel. Gaddis fills Carpenter’s Gothic with birds—in fact, the first words of the novel are “The bird”—a motif that underscores the possibility of flight, of escape (and entails its opposite–confinement, imprisonment). These crows are pure Halloween, shredding small mammals as the wild boys smash pumpkins. Elizabeth exits the house (a rare vignette in Carpenter’s Gothic, which keeps her primarily confined inside it) to check the mail. The only message that has been delivered to her though is from the Halloween tricksters, who cruelly laugh at their prank. The pornographic image, ripped from a magazine, is described in such a way that the blonde woman trapped within it comes to life, “in forthright complicity,” making eye contact with Elizabeth. There’s an intimation of aggressive sexual violence underlying the prank, whether the boys understand this or not. The scrap of paper doubles their earlier signal, the shaving creamed fuck written on the garage door.

Elizabeth recovers herself to signify steadiness in return, demonstratively crumpling the pornographic scrap—but she takes it with her, back into the house, where it joins the other heaps of papers, scraps, detritus of media and writing that make so much of the content of the novel. Here, the pornographic scrap takes on its own sinister force. Initially, Elizabeth sets out to compose herself anew; the next paragraph finds her descending the stairs, “differently dressed now, eyeliner streaked on her lids and the

colour unevenly matched on her paled cheeks,” where she answers the ringing phone with “a quaver in her hand.” The scene that follows is an extraordinary displacement in which the phone takes on a phallic dimension, and Elizabeth imaginatively correlates herself with the blonde woman in the pornographic picture. She stares at this image the whole time she is on the phone while a disembodied male voice demands answers she cannot provide:

The voice burst at her from the phone and she held it away, staring down close at the picture as though something, some detail, might have changed in her absence, as though what was promised there in minutes, or moments, might have come in a sudden burst on the wet lips as the voice broke from the phone in a pitch of invective, in a harried staccato, broke off in a wail and she held it close enough to say —I’m sorry Mister Mullins, I don’t know what to… and she held it away again bursting with spleen, her own fingertip smoothing the still fingers hoarding the roothairs of the inflexible surge before her with polished nails, tracing the delicate vein engorged up the curve of its glistening rise to the crown cleft fierce with colour where that glint of beading led off in its fine thread to the still tongue, mouth opened without appetite and the mascaraed eyes unwavering on hers without a gleam of hope or even expectation, —I don’t know I can’t tell you!

Gaddis’s triple repetition of the verb burst links the phone to the phallus and links Elizabeth to the blonde woman. This link is reinforced by the notation of the woman’s “mascaraed eyes,” a detail echoing the paragraph’s initial image of Elizabeth descending the stairs with streaked eyeliner. The final identification between the two is the most horrific—Elizabeth reads those eyes, that image, that scrap of paper, as a work “without a gleam of hope or even expectation.” Doom.

Elizabeth is “saved,” if only temporarily, by the unexpected arrival of the mysterious Mr. McCandless, who quickly stabilizes the poor woman. Gaddis notes that McCandless “caught the newel with her hand…He had her arm, had her hand in fact firm in one of his.” When he asks why she is so upset, she replies, “It’s the, just the mess out there, Halloween out there…” McCandless chalks the mess up to “kids with nothing to do,” but Elizabeth reads in it something more sinister: “there’s a meanness.” McCandless counters that “it’s plain stupidity…There’s much more stupidity than there is malice in the world.” This phrase “Halloween out there” repeats three times in the chapter, suggesting a larger signification—it isn’t just Halloween tonight, but rather, as McCandless puts it, the night is “Like the whole damned world isn’t it.” It’s always Halloween out there in Carpenter’s Gothic, and this adds up to mostly malice of mostly stupidity in this world—depending on how you read it.

The second half of the chapter gives over to McCandless, who comes to unexpectedly inhabit the novel’s center. Elizabeth departs, if only for a few hours, leaving McCandless alone, if only momentarily. A shifty interlocutor soon arrives on the thresh hold of his Carpenter Gothic home, and we learn some of his fascinating background. It’s a strange moment in a novel that has focused so intently on the consciousness of Elizabeth, but coming in the novel’s center, it acts as a stabilizing force. I won’t go into great detail here—I think much of what happens when McCandless is the center of the narrative is best experienced without any kind of spoiler—but we get at times from him a sustained howl against the meanness and stupidity of the world. He finally ushers his surprise interlocutor out of his home with the following admonition: “It’s Halloween out there too.”

[Ed. note–Biblioklept first published this post in October of 2018.]

I ended up reading the last two chapters of William Gaddis’s novel Carpenter’s Gothic a few times, trying to figure out exactly what happened. I then read Steven Moore’s excellent essay on the novel, “Carpenter’s Gothic or, The Ambiguities.” (If you have library access to the Infobase database Bloom’s Literature, you can find the essay there; if not, here’s a .pdf version). Moore offers a tidy summary of Carpenter’s Gothic—a summary which should be avoided by anyone who wants to read the novel. Because Carpenter’s Gothic isn’t so much about what happens but how it happens. Moore writes:

As is the case with any summary of a Gaddis novel, this one not only fails to do justice to the novel’s complex tapestry of events but also subverts the manner in which these events are conveyed. Opening Carpenter’s Gothic is like opening the lid of a jigsaw puzzle: all the pieces seem to be there, but it is up to the reader to fit those pieces together. …Even after multiple readings, several events remain ambiguous, sometimes because too little information is given, sometimes because there are two conflicting accounts and no way to confirm either.

Moore then lays out the novel’s theme in clear, precise language:

Such narrative strategies are designed not to baffle or frustrate the reader but to dramatize the novel’s central philosophic conflict, that between revealed truth versus acquired knowledge. Nothing is “revealed” by a godlike omniscient narrator in this novel; the reader learns “what really happens” only through study, attention, and the application of intelligence.

Quite frankly, Moore has written an essay that I wish I had written myself. I had been sketching parallels between Carpenter’s Gothic and Leslie Fiedler’s classic study Love and Death in the American Novel all throughout my reading; Moore ends up citing Fiedler a few times in his essay, in particularly working from Fiedler’s idea of how Gothicism manifests in American writing. (Moore does not bring up Fiedler’s critique of masculinity though, which opens up an occasion for me to write—once I’ve reread the puzzle though).

Anyway—I loved loved loved Carpenter’s Gothic, and I read it at just about the right time: It’s a Halloween novel. Great stuff.

In line with the Halloween theme: I had been working on a post about horror, about how I love scary films, grotesque literature, and weird art, because fantasy evocations of terror offer a reprieve from anxiety, from true dread, etc. Like, you know, a climate change report—I mean, that’s genuinely horrifying. But scary films and scary stories almost never really scare me. So I was thinking about literature that does produce dread in me, anxiety in me, and listing out examples in my draft, and so well anyway I reread Roberto Bolaño’s short story “Last Evenings on Earth.” I wrote about the collection named for the story almost a decade ago on this blog, focusing on the “ebb and flow between dread and release, fear and humor, ironic detachment and romantic idealism” in the tales:

In “Last Evenings on Earth,” B takes a vacation to Acapulco with his father. Bolaño’s rhetoric in this tale is masterful: he draws each scene with a reportorial, even terse distance, noting the smallest of actions, but leaving the analytical connections up to his reader. Even though B sees his holiday with his dad heading toward “disaster,” toward “the price they must pay for existing,” he cannot process what this disaster is, or what paying this price means. The story builds to a thick, nervous dread, made all the more anxious by the strange suspicion that no, things are actually fine, we’re all just being paranoid here. (Not true!)

I’m not sure if I’ll get the essay I was planning together any time soon, but I’m glad I reread “Last Evenings.”

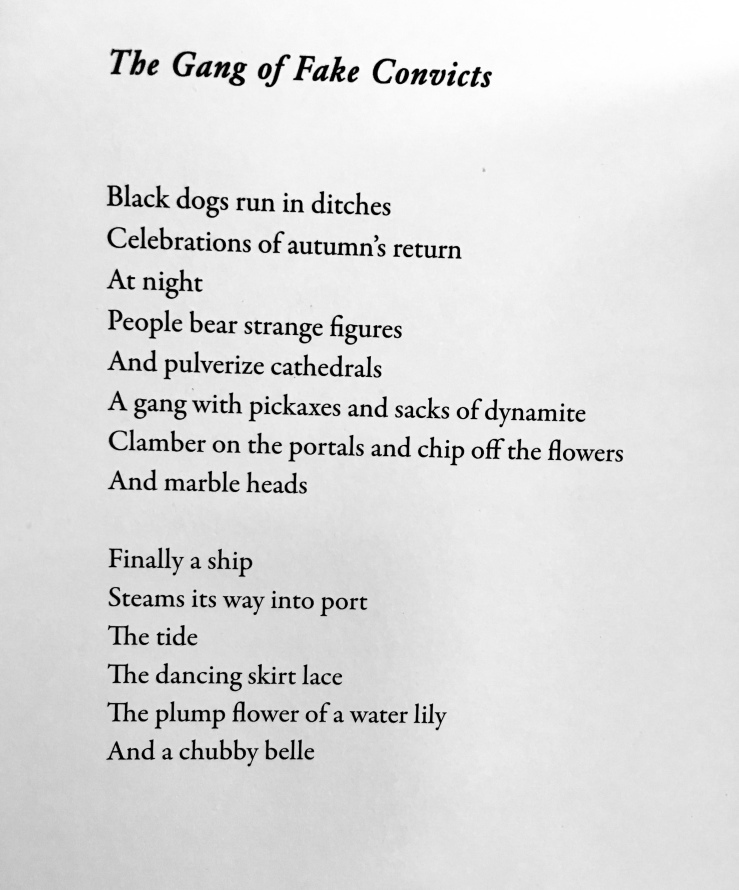

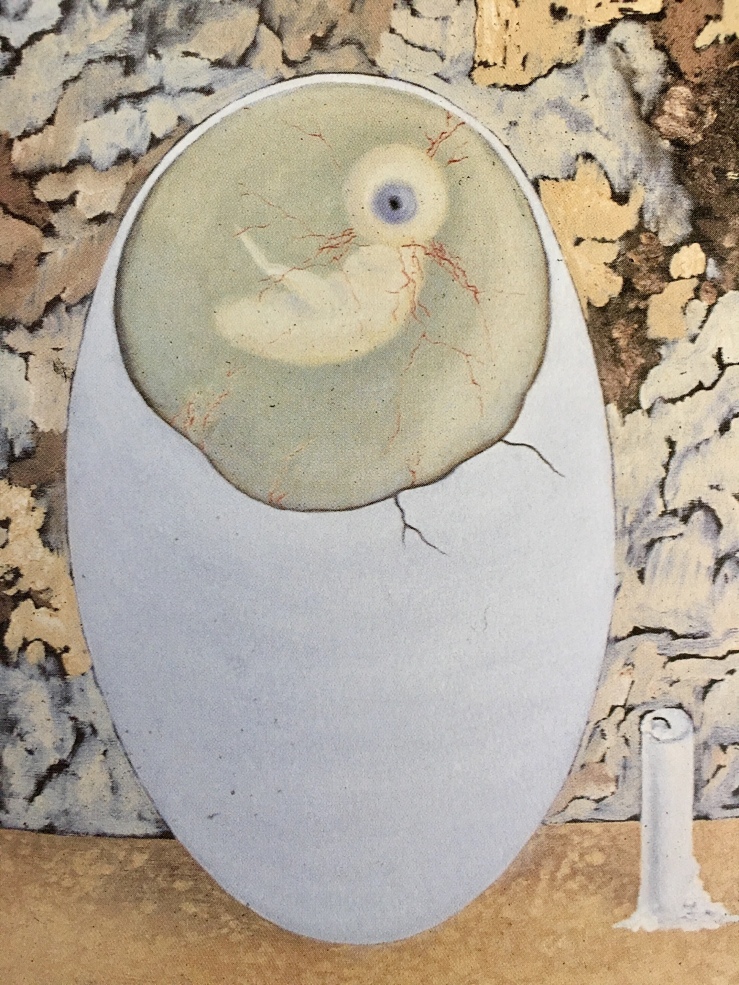

There’s a strange background plot in “Last Evenings” in which Bolaño’s stand-in “B” dwells over a book of French surrealist poets, one of whom disappears mysteriously. Jindřich Štyrský isn’t French—he’s Czech—but he was a surrealist poet (and artist and essayist and etc.), so I couldn’t help inserting him into Bolaño’s story. I’ve been reading Dreamverse, which ripples with sensual horror. I wrote about it here. Here’s one of Štyrský’s poems (in English translation by Jed Slast); I think you can get the flavor from this one:

And here’s a detail from his 1937 painting Transformation:

I’ve finished the first section of David Bunch’s Moderan, which is a kind of post-nuke dystopia satire on toxic masculinity. While many of the tropes for these stories (most of which were written in the 1960s and ’70s) might seem familiar—cyborgs and dome homes, caste systems and ultraviolence, a world of made and not born ruled by manunkind (to steal from E.E. Cummings)—it’s the way that Bunch conveys this world that is so astounding. Moderan is told in its own idiom; the voice of our narrator Stronghold-10 booms with a bravado that’s ultimately undercut by the authorial irony that lurks under its surface. I will eventually write a proper review of Moderan, but the book seems equal to the task of satirizing the trajectory of our zeitgeist.

I started Angela Carter’s novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman last night and the first chapter is amazing.

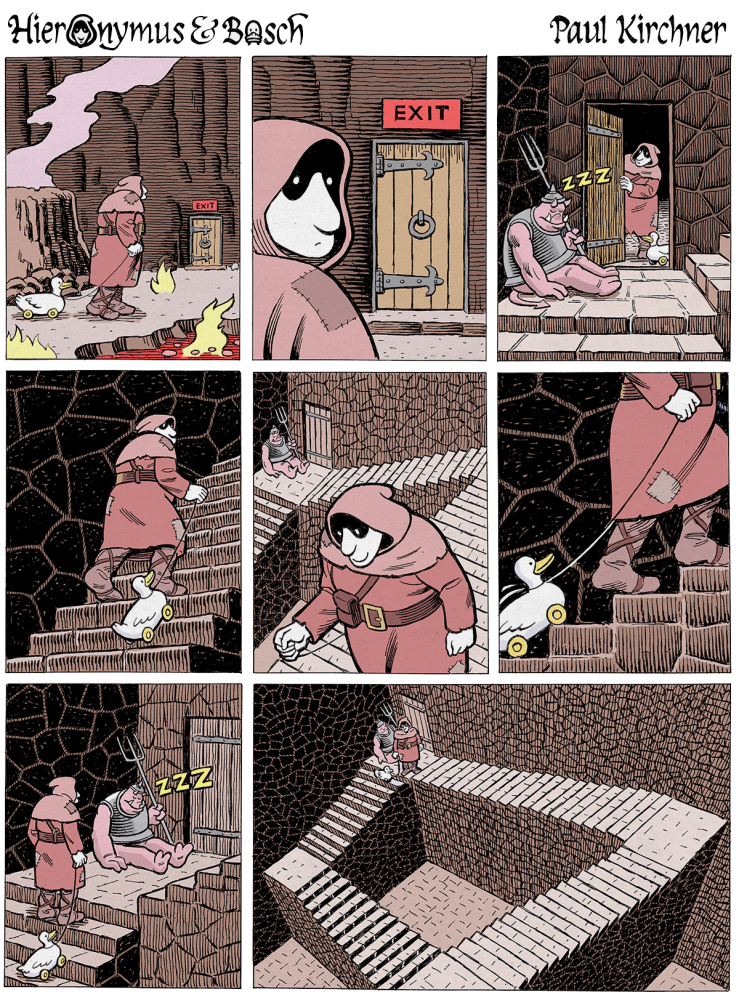

Finally, I got a hard copy of Paul Kirchner’s new collection, Hieronymus & Bosch which finds humor in the horror of hell. The collection is lovely—I should have a post about it here later this week and hopefully a review at The Comics Journal later this month. For now though, a sample strip:

In its sixth (and penultimate chapter), William Gaddis’s 1985 novel Carpenter’s Gothic includes a rare scene. Our heroine Elizabeth Booth exits the house she spends most of the book confined in and actually looks at it from the outside. With her is the house’s owner, the mysterious Mr. McCandless:

—I’ve never really looked at it.

—At what… looking where she was looking.

—At the house. From outside I mean.

Carpenter’s Gothic is a novel of utter interiority—the reader never makes it but a few feet out of the house, and only then on rare occasions. This postmodern Gothic novel tingles with a smothering claustrophobia, its insularity underscored by continual references to other spaces outside the house. The possibility of an outside world waiting for Elizabeth is realized through dialogue with her husband Paul, her brother Billy, and mysterious Mr. McCandless, as well as the non-stop (and, from the reader’s perspective, one-sided) telephone conversations that make up so much of the novel’s material. And yet with all its references to traveling away to California, Africa, New York City, Acapulco, etc., Carpenter’s Gothic keeps Elizabeth locked away in the old house, tethered to the umbilical phone cord at the novel’s center.

McCandless is off in his own interior space—the shifting tortured howl of his own consciousness—when Elizabeth remarks that she has never really seen the house from the outside. Her observation raises him “to the surface” of concrete reality:

—Oh the house yes, the house. It was built that way yes, it was built to be seen from outside it was, that was the style, he came on, abruptly rescued from uncertainty, raised to the surface —yes, they had style books, these country architects and the carpenters it was all derivative wasn’t it, those grand Victorian mansions with their rooms and rooms and towering heights and cupolas and the marvelous intricate ironwork.

The house is built in the Carpenter Gothic style (sometimes called Rural Gothic style), which essentially amounts to an American imitation of European Gothic’s forceful elegance. McCandless continues:

That whole inspiration of medieval Gothic but these poor fellows didn’t have it, the stonework and the wrought iron. All they had were the simple dependable old materials, the wood and their hammers and saws and their own clumsy ingenuity bringing those grandiose visions the masters had left behind down to a human scale with their own little inventions, those vertical darts coming down from the eaves? and that row of bull’s eyes underneath?

McCandless, stand-in for Gaddis, performs a metatextual interpretation for the reader. The Carpenter Gothic is Carpenter’s Gothic, the American postGothic reinterpreation of the European form—namely, the Gothic novel. The materials Gaddis uses to build his book are the materials of mass media and mass textuality. He condenses high literature, lurid newspaper clippings, mail, textbook pages, scraps of illegible notes, pornographic centerfolds, and every other manner of paper into a postGothic synthesis. And not just paper, but also the telephone (always ringing) and the radio (always on, always tuned to inhuman human voices). And the television too, tuned to Orson Welles as Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre (dir. Robert Stevenson, 1943), a film which weaves its way in and out of Elizabeth’s consciousness in the beginning of the novel, planting seeds of romance and locked rooms and secrets and fire.

But I’ve cut off McCandless, who was just about to give us another neat description of the Carpenter Gothic, which is to say another neat description of Carpenter’s Gothic:

He was up kicking leaves aside, gesturing, both arms raised embracing —a patchwork of conceits, borrowings, deceptions, the inside’s a hodgepodge of good intentions like one last ridiculous effort at something worth doing even on this small a scale, because it’s stood here, hasn’t it, foolish inventions and all it’s stood here for ninety years…

Carpenter’s Gothic is more than just a hodgepodge or patchwork; it is more than a ridiculous effort; it is more than the sum of its foolish inventions. Gaddis gives us something new, a postmodern Gothic analysis of the end of the American century.

McCandless, Gaddis’s stand-in, wants to put all the pieces together. He echoes Jack Gibbs, the (anti-)hero (and fellow Gaddis stand-in) of J R, and he prefigures the narrator of Gaddis’s last novel, Agapē Agape, who, like Gibbs, strives to stitch together something from the atomized scraps and remnants of the 20th century. Gaddis’s protagonists contend with entropy and attempt to get the detritus of the modern world “sorted and organized.” The push-pull of hope and despair drives these protagonists, but often drives them too far.

And McCandless’s reverie takes him too far, again into the interiority of his skull:

…breaking off, staring up where her gaze had fled back with those towering heights and cupolas, as though for some echo: It’s like the inside of your head McCandless, if that was what brought him to add —why when somebody breaks in, it’s like being assaulted, it’s the…

In a moment of self-speech, McCandless realizes that the Carpenter Gothic is “like the inside of [his] head,” underscoring his connection to his creator, Gaddis, as well as the connection between the house and the novel.

The (always) ringing phone punctures the scene:

—Listen! The phone had rung inside and she started up at the second ring, sank back with the third. —All I meant was, it’s a hard house to hide in…

Elizabeth’s lines here emphasize Carpenter’s Gothic’s central Gothicism—the Carpenter Gothic and Carpenter’s Gothic is a hard place to hide in. Secrets will out.

And so well where does our hodgepodge of good intentions lead?

—but did you ever think? She was up on that elbow again, turned to him so his hand fell still on the white of the sheet, —about light years?

—About what?

—I mean if you could get this tremendously powerful telescope? and then if you could get far enough away out on a star someplace, out on this distant star, and you could watch things on the earth that happened a long time ago really happening? Far enough away, he said, you could see history, Agincourt, Omdurman, Crécy… How far away were they she wanted to know, what were they, stars? constellations? Battles he told her, but she didn’t mean battles, she didn’t want to see battles, —I mean seeing yourself… Well as far as that goes he said, get a strong enough telescope you could see the back of your own head, you could —That’s not what I meant. You make fun of me don’t you.

—Certainly not, why would…

—I mean seeing what really happened back when…

—All right, set up a mirror on Alpha Centauri then, you’d sit right here with your telescope watching yourself four, about four and a half years ago is that what you…

—No.

—But I thought…

—Because I don’t want to see that! She pulled away, pulled up the sheet, staring up at the ceiling. —But you’d just see the outside though, wouldn’t you. You’d just see the mountain you’d see it go down and you’d see all the flames but you wouldn’t see inside, you wouldn’t see those faces again and the, and you wouldn’t hear it, a million miles away you wouldn’t hear the screams… What screams, he wanted to —No, no that one’s too close, find one further away… and he subsided, looking at the sheet clenched to her throat and the length of her gone under it, recommending Sirius, setting up business on the Dog Star, the brightest of them all, watching what happened eight and a half? nine years ago? —I told you what happened… the sheet clenched firm, —I told you last night no, twenty, twenty five years away when it was all still, when things were still like you thought they were going to be?

From the beginning of the fifth chapter of William Gaddis’s 1985 novel Carpenter’s Gothic. I’d never heard of this thought experiment until now.

The fourth of seven unnumbered chapters in William Gaddis’s Carpenter’s Gothic is set over the course of Halloween, moving from morning, into afternoon, and then night. Halloween is an appropriately Gothic setting for the midpoint of Gaddis’s postmodern Gothic novel, and there are some fascinating turns in this central chapter.

A summary with spoilers is not necessary here. Suffice to say that our heroine Elizabeth Booth is left alone on Halloween in the dilapidated Rural Gothic style house she and her awful husband Paul rent from mysterious Mr. McCandless. As Paul exits the house to go on one his many fruitless business trips, he notices that some neighborhood kids have already played their Halloween tricks:

He had the front door open but he stood there, looking out, looking up, —little bastards look at that, not even Halloween till tonight but they couldn’t wait… Toilet paper hung in disconsolate streamers from the telephone lines, arched and drooped in the bared maple branches reaching over the windows of the frame garage beyond the fence palings where shaving cream spelled fuck. —Look keep the doors locked, did this last night Christ knows what you’re in for tonight… and the weight of his hand fell away from her shoulder, —Liz? just try and be patient? and he pulled the door hard enough for the snap of the lock to startle her less with threats locked out than herself locked in, to leave her steadying a hand on the newel…

The kids’ Halloween antics take on a particularly sinister aspect here, set against the stark New England background Gaddis conjures. We get gloomy streamers, desolate trees, and the bald, ugly signification of one lone word: fuck. (Fuck and its iterations, along with Gaddis’s old favorite God damn, are bywords in Carpenter’s Gothic). Paul’s reading of this scene is also sinister; he underscores the Gothic motif in telling Elizabeth to “keep the doors locked” because she doesn’t know what she’s “in for tonight.” Tellingly, the aural snap of Paul’s exit shows us that Elizabeth is ultimately more paranoid about being locked in. Indeed, by the middle of the novel, we see her increasingly trapped in her (haunted) house. The staircase newel, an image that Gaddis uses repeatedly in the novel, becomes her literal support. Elizabeth spends the rest of the morning avoiding chores before eventually vomiting and taking a nap.

Then, Gaddis propels us forward a few hours with two remarkable paragraphs (or, I should say, two paragraphs upon which I wish to remark). Here is the first post-nap paragraph:

She woke abruptly to a black rage of crows in the heights of those limbs rising over the road below and lay still, the rise and fall of her breath a bare echo of the light and shadow stirred through the bedroom by winds flurrying the limbs out there till she turned sharply for the phone and dialed slowly for the time, up handling herself with the same fragile care to search the mirror, search the world outside from the commotion in the trees on down the road to the straggle of boys faces streaked with blacking and this one, that one in an oversize hat, sharing kicks and punches up the hill where in one anxious glimpse the mailman turned the corner and was gone.

What a fantastic sentence. Gaddis’s prose here reverberates with sinister force, capturing (and to an extent, replicating) Elizabeth’s disorientation. Dreadful crows and flittering shadows shake Elizabeth, and searching for stability she telephones for the time. (If you are a young person perhaps bewildered by this detail: This is something we used to do. We used to call a number for the time. Like, the time of day. You can actually still do this. Call the US Naval Observatory at 202-762-1069 if you’re curious what this aesthetic experience is like). The house’s only clock is broken, further alienating Elizabeth from any sense of normalcy. In a mode of “fragile care,” anxious Elizabeth glances in the mirror, another Gothic symbol that repeats throughout this chapter. She then spies the “straggle of boys” (a neat parallel to the “black rage of crows” at the sentence’s beginning) already dressed up in horrorshow gear for mischief night and rumbling with violence. The mailman—another connection to the outside world, to some kind of external and steadying authority—simply disappears.

Here is the next paragraph:

Through the festoons drifting gently from the wires and branches a crow dropped like shot, and another, stabbing at a squirrel crushed on the road there, vaunting black wings and taking to them as a car bore down, as a boy rushed the road right down to the mailbox in the whirl of yellowed rust spotted leaves, shouts and laughter behind the fence palings, pieces of pumpkin flung through the air and the crows came back all fierce alarm, stabbing and tearing, bridling at movement anywhere till finally, when she came out to the mailbox, stillness enveloped her reaching it at arm’s length and pulling it open. It looked empty; but then there came sounds of hoarded laughter behind the fence palings and she was standing there holding the page, staring at the picture of a blonde bared to the margin, a full tumid penis squeezed stiff in her hand and pink as the tip of her tongue drawing the beading at its engorged head off in a fine thread. For that moment the blonde’s eyes, turned to her in forthright complicity, held her in their steady stare; then her tremble was lost in a turn to be plainly seen crumpling it, going back in and dropping it crumpled on the kitchen table.

The paragraph begins with the Gothic violence of the crows “stabbing and tearing” at a squirrel. Gaddis fills Carpenter’s Gothic with birds—in fact, the first words of the novel are “The bird”—a motif that underscores the possibility of flight, of escape (and entails its opposite–confinement, imprisonment). These crows are pure Halloween, shredding small mammals as the wild boys smash pumpkins. Elizabeth exits the house (a rare vignette in Carpenter’s Gothic, which keeps her primarily confined inside it) to check the mail. The only message that has been delivered to her though is from the Halloween tricksters, who cruelly laugh at their prank. The pornographic image, ripped from a magazine, is described in such a way that the blonde woman trapped within it comes to life, “in forthright complicity,” making eye contact with Elizabeth. There’s an intimation of aggressive sexual violence underlying the prank, whether the boys understand this or not. The scrap of paper doubles their earlier signal, the shaving creamed fuck written on the garage door.

Elizabeth recovers herself to signify steadiness in return, demonstratively crumpling the pornographic scrap—but she takes it with her, back into the house, where it joins the other heaps of papers, scraps, detritus of media and writing that make so much of the content of the novel. Here, the pornographic scrap takes on its own sinister force. Initially, Elizabeth sets out to compose herself anew; the next paragraph finds her descending the stairs, “differently dressed now, eyeliner streaked on her lids and the

colour unevenly matched on her paled cheeks,” where she answers the ringing phone with “a quaver in her hand.” The scene that follows is an extraordinary displacement in which the phone takes on a phallic dimension, and Elizabeth imaginatively correlates herself with the blonde woman in the pornographic picture. She stares at this image the whole time she is on the phone while a disembodied male voice demands answers she cannot provide:

The voice burst at her from the phone and she held it away, staring down close at the picture as though something, some detail, might have changed in her absence, as though what was promised there in minutes, or moments, might have come in a sudden burst on the wet lips as the voice broke from the phone in a pitch of invective, in a harried staccato, broke off in a wail and she held it close enough to say —I’m sorry Mister Mullins, I don’t know what to… and she held it away again bursting with spleen, her own fingertip smoothing the still fingers hoarding the roothairs of the inflexible surge before her with polished nails, tracing the delicate vein engorged up the curve of its glistening rise to the crown cleft fierce with colour where that glint of beading led off in its fine thread to the still tongue, mouth opened without appetite and the mascaraed eyes unwavering on hers without a gleam of hope or even expectation, —I don’t know I can’t tell you!

Gaddis’s triple repetition of the verb burst links the phone to the phallus and links Elizabeth to the blonde woman. This link is reinforced by the notation of the woman’s “mascaraed eyes,” a detail echoing the paragraph’s initial image of Elizabeth descending the stairs with streaked eyeliner. The final identification between the two is the most horrific—Elizabeth reads those eyes, that image, that scrap of paper, as a work “without a gleam of hope or even expectation.” Doom.

Elizabeth is “saved,” if only temporarily, by the unexpected arrival of the mysterious Mr. McCandless, who quickly stabilizes the poor woman. Gaddis notes that McCandless “caught the newel with her hand…He had her arm, had her hand in fact firm in one of his.” When he asks why she is so upset, she replies, “It’s the, just the mess out there, Halloween out there…” McCandless chalks the mess up to “kids with nothing to do,” but Elizabeth reads in it something more sinister: “there’s a meanness.” McCandless counters that “it’s plain stupidity…There’s much more stupidity than there is malice in the world.” This phrase “Halloween out there” repeats three times in the chapter, suggesting a larger signification—it isn’t just Halloween tonight, but rather, as McCandless puts it, the night is “Like the whole damned world isn’t it.” It’s always Halloween out there in Carpenter’s Gothic, and this adds up to mostly malice of mostly stupidity in this world—depending on how you read it.

The second half of the chapter gives over to McCandless, who comes to unexpectedly inhabit the novel’s center. Elizabeth departs, if only for a few hours, leaving McCandless alone, if only momentarily. A shifty interlocutor soon arrives on the thresh hold of his Carpenter Gothic home, and we learn some of his fascinating background. It’s a strange moment in a novel that has focused so intently on the consciousness of Elizabeth, but coming in the novel’s center, it acts as a stabilizing force. I won’t go into great detail here—I think much of what happens when McCandless is the center of the narrative is best experienced without any kind of spoiler—but we get at times from him a sustained howl against the meanness and stupidity of the world. He finally ushers his surprise interlocutor out of his home with the following admonition: “It’s Halloween out there too.”

I have blazed through the first three (unnumbered) chapters of William Gaddis’s third novel Carpenter’s Gothic (1985) this weekend, consuming the prose with an urgency I did not expect. After all, Gaddis is (at least according to Jonathan Franzen) “Mr. Difficult,” right?

But Carpenter’s Gothic is not especially difficult, or does not feel that way to me, anyway—although I’m sure I find it so readable in large part because I’ve read Gaddis’s second novel J R twice already, and Carpenter’s Gothic is written in the same style as J R. The first time I read J R I did find its style tremendously challenging. Gaddis strips almost all exposition and scene-setting in J R. The novel’s 726 pages are comprised primarily in dialogue, often unattributed, leaving the reader to play director, producer, and cinematographer. Reading it a second time was, in a way, like reading it for the first time, revealing one of the best and arguably most important American novels of the second-half of the twentieth century.

In any case, reading J R has taught me how to read Carpenter’s Gothic, which is told in the same style. Carpenter’s Gothic is a smaller novel though, both literally (around 250 pages) and figuratively. While J R sports a large cast, sprawling and interlinked plots, divergent tones, and a wide array of themes, Carpenter’s Gothic is restrained to a few talking characters, whom Gaddis keeps confined to an isolated house somewhere in New England. (It is from this house’s architectural design that the novel gets its title).

The central character is Elizabeth Booth, 33, an heiress locked out of her inheritance. Elizabeth is married to an awful abusive man named Paul, a racist Vietnam Veteran who embodies almost every characteristic of what we now think of as toxic masculinity. Elizabeth is recovering from an as-yet-unspecified accident, and spends most of her time confined to her rented house, fielding phone calls. Some of these phone calls are from folks related to her husband’s latest scheme with a televangelist. Other calls are from her friend Edith who has run off to sunny Jamaica—a prospect of escape that entices Elizabeth. Even more calls come for the mysterious owner of the house, McCandless, who eventually shows up in the third chapter.

McCandless’s visit sparks something in Elizabeth. She gets to glance into his locked study, crammed with papers and books and even a piano, and she takes him for a writer, but he claims he’s a geologist. His short visit inspires Elizabeth to dig up the draft of a book, or something like a book, she’s been working on, and add a few notes. The romantic impulse is eventually punctured by her husband’s return.

Carpenter’s Gothic’s relentless interiority and inherent bitterness can give the novel a claustrophobic feeling, and reading it often reminds me of the scenes in J R that are set in the ramshackle 96th Street apartment shared by Bast and Gibbs. And yet its interiority always branches outward, evoking an exotic and pulsating world that Elizabeth might love to experience. There’s Montego Bay, there’s Orson Welles in Jane Eyre, there’s the nomadic Masai of central east Africa. Etc. But Elizabeth’s experiences are mediated by newspapers, magazine articles, phone calls, and old movies on television. It’s quite sad and frustrating.

Elizabeth thus far fits neatly into American literature’s motif of the confined woman: Walt Whitman’s 29th bather, Kate Chopin’s Mrs. Mallard, William Carlos Williams’ young housewife, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s distressed and nervous heroine. There are many, many more, of course. I’m not quite half way through Carpenter’s Gothic–no spoilers from you please, readers!—and curious what Gaddis will do with his heroine. Will there be an escape? Freedom? A happy ending?

So many 19th and 20th century American writers seemed unsure of what to do with their heroines, even after they had freed them (Kate Chopin’s Edna Pontellier is a particularly easy go-to example, but again: there are more). Carpenter’s Gothic seems set on a tragic track, but Gaddis has a way of making his readers recognize the farcical contours in tragedy.

I haven’t given a taste of Gaddis’s prose yet. I will share, as a closing, the novel’s opening two-sentence paragraph, which I think is simply marvelous, and which I had to read at least three times before I could turn to the novel’s second page. Here it is:

The bird, a pigeon was it? or a dove (she’d found there were doves here) flew through the air, its colour lost in what light remained. It might have been the wad of rag she’d taken it for at first glance, flung at the smallest of the boys out there wiping mud from his cheeks where it hit him, catching it up by a wing to fling it back where one of them now with a broken branch for a bat hit it high over a bough caught and flung back and hit again into a swirl of leaves, into a puddle from rain the night before, a kind of battered shuttlecock moulting in a flurry at each blow, hit into the yellow dead end sign on the corner opposite the house where they’d end up that time of day.

From Matthew Erickson’s article “Mysterious Skin: The Realia of William Gaddis” at The Paris Review. From the article:

What the researcher, or even the dilettante, might want to know is how an author’s material surroundings and posthumous personal effects might distill and leak into their work. Most often, the realia from a literary archive are the typical objects that we would associate with the physical act of writing, such as it is: fountain pens, stationery, reading glasses, ashtrays. Essentially, these objects are to dead authors what the items in Hard Rock Cafe display cases are to dead rock stars: memorabilia. Hendrix’s famous acid-soaked headband or Faulkner’s famous tin of beloved pipe tobacco, take your pick. This fact makes an author’s nonwriterly objects stand out and seem more significant, more imbued with potential coded meaning. Indeed, zebras and their skins do make appearances within Gaddis’s fiction, so the poor beast in the special collections isn’t entirely irrelevant when considering his corpus. A rolled-up zebra skin appears midway through Carpenter’s Gothic (“He’d kicked aside a cobwebbed roll of canvas, the black on white, or was it white on black roll of a hide …”), sporadically emerging from the silent background and into the incessant stream of dialog that makes up the majority of the text. In JR, the downtrodden composer Edward Bast is commissioned to write a score of “zebra music” for a documentary being made by the big-game hunter and stockbroker Crawley, in a lobbying effort to convince Congress to introduce various African species, zebras included, into the U.S. National Parks system…