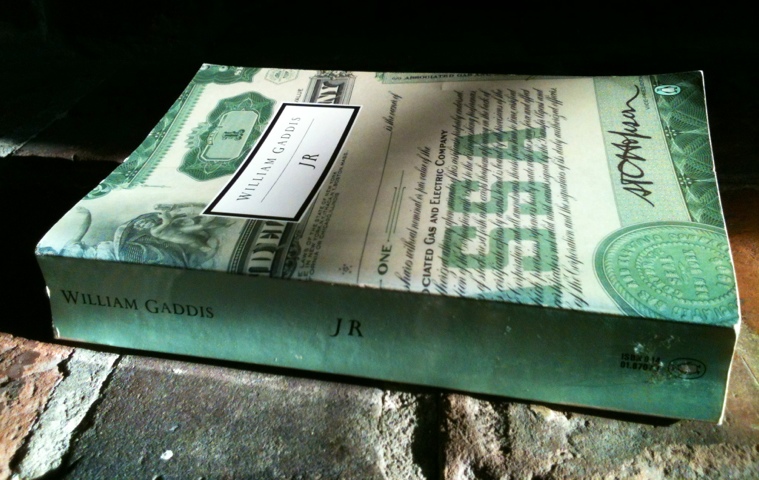

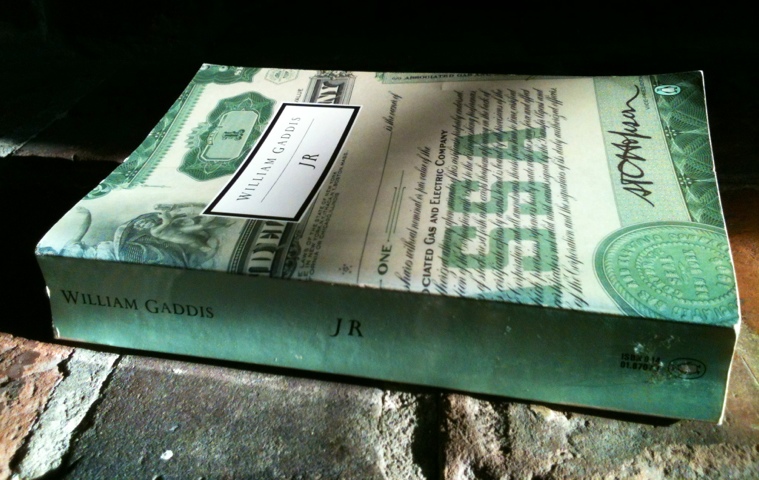

1. Let me point those of you who may care to my first riff on William Gaddis’s J R, which I wrote about half way into the book, and which will likely provide more context than I’m prepared to offer here. Also, there might be spoilers ahead.

2. The end of J R is heartbreaking. We find some of our principal characters—Bast, Gibbs, and JR—in nebulous spaces, their plans and dreams and hopes crumbling or smoking or fizzing out or jettisoned (pick your verb as I’m too lazy or unequipped).

3. The final face-to-face scene between Bast and JR, the one that begins with them riding in a limousine and ends with Bast’s psycho breakdown—heartbreaking. Little JR, we realize, is most motivated by his intense need for human connection, his desire for family, perhaps, or place, at least. Bast’s rejection of JR—really a rejection of contemporary consumer culture—is almost horrific, even more so because the reader (this reader, anyway) so readily identifies with Bast and JR simultaneously.

4. Here’s Gaddis on his character JR (from The Paris Review interview):

The boy himself is a total invention, completely sui generis. The reason he is eleven is because he is in this prepubescent age where he is amoral, with a clear conscience, dealing with people who are immoral, unscrupulous; they realize what scruples are, but push them aside, whereas his good cheer and greed he considers perfectly normal. He thinks this is what you’re supposed to do; he is not going to wait around; he is in a hurry, as you should be in America—get on with it, get going. He is very scrupulous about obeying the letter of the law and then (never making the distinction) evading the spirit of the law at every possible turn. He is in these ways an innocent and is well-meaning, a sincere hypocrite. With Bast, he does think he’s helping him out.

5. And again:

INTERVIEWER

Which is the novel you care most for?

GADDIS

I think that I care most for JR because I’m awfully fond of the boy himself.

6. In that same interview, Gaddis contends that JR is motivated by “good-natured greed,” which is probably true (see above re: letter vs. spirit). Despite his predatory capitalism, his willingness to strip company employees of basic safety nets, JR remains sympathetic.

7. Why is JR a sympathetic character? He’s just a child, one who lives in a world without adult supervision let alone love and care. In a touching scene that telegraphs the bizarre black humor that runs through the novel, JR suggests that the Eskimos on display at a museum are the work of a taxidermist: That is, said Eskimos were once, like, alive, and are now on display. Amy Joubert, his social studies teacher (and the object of Gibbs’s and possibly Bast’s affection) is moved to both pity and terror by JR’s confusion, and clutches him to her breast.

8. While we’re on Eskimos, which is to say Native Americans, which is to say, perhaps, Indians: The Indian plot in JR fascinates; it recapitulates a bloody, awful past, pointing to the brutal way the quote unquote invisible hand of the market might sweep entire people away and then come back (in a cheap costume) to offer modernity at a price.

9. Ethnic minorities in general find themselves displaced in JR, or at least displaced in the language of JR (and is there a novel that is more language than JR, if such a statement might be permitted to exist (at least metaphorically)? No, I don’t think there is, or at least I don’t know of one). The casual racism of 1%ers like Zona Selk and Cates is ugly and bitter, but the PR man Davidoff is somehow worse—he sees race as something to use, to manipulate, to control.

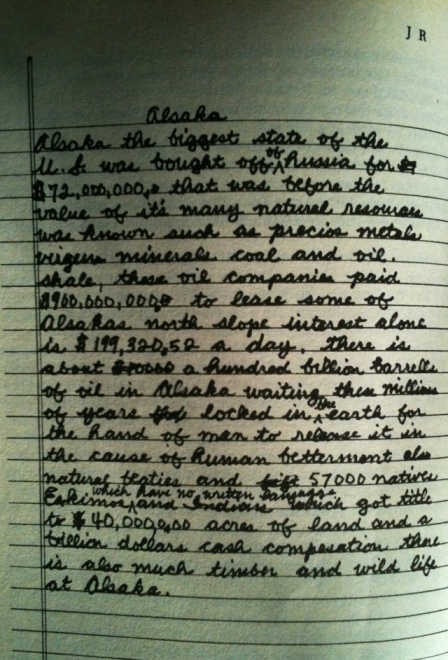

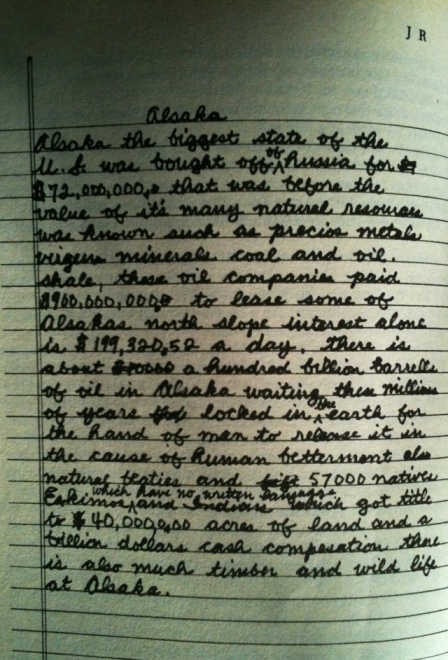

10. And, of course, JR’s infamous “Alsaka Report,” a connection to Manifest Destiny, to the valuation of our ecosystem in the most base and short-sighted terms (there’s a perhaps overlooked streak of environmentalism to JR):

11. Sci-fi elements to JR: The Frigicom process, which promises to freeze noise. The Teletravel transmission process.

12. At the end of JR, we learn that poor diCephalis is lost in Teletravel transmission.

13. I couldn’t help but be reminded—repeatedly—of David Foster Wallace’s work during JR (diCephalis stuck in Teletravel recalls poor Orin in the giant glassjar at the end of Infinite Jest). In general, the loose threads of JR recall Wallace’s loose threads (other way round, I know).

14. The phone motif alone might have led me to compare Wallace to Gaddis—but there’s also all that, y’know, thematic unity.

15. And clearly, too, style. I’m sure that longtime readers of Gaddis have likely made the comparisons already, but throughout his work, Wallace repeatedly uses chapters or sections that comprise only dialogue. A good example is §19 of The Pale King (which I riffed on a bit this summer), a conversation between three IRS agents stuck in an elevator. In some ways, the scene, set only a few years after the publication of JR feels like a strange little sequel, or an echo of a shadow of a chapter of a sequel (or maybe not—just riffing here). Wallace’s concerns about civics, ethics, and compassion seem more straightforward than Gaddis’s angry vision of a desacralized world, a world where symphonies must be chopped into three minute segments to allow for commercial interruptions (or, rather, that symphonies must interrupt commercials). Wallace is obviously writing after the victory of Pop Art, of populism, of the slow sprawling stripmalling of America . . . but I’ve riffed off track (there is no track).

16. ” . . . I mean they never lose these banks don’t, I mean where we’re getting screwed . . . ” — JR laments on page 653 of my Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition.

17. The above quote as the briefest illustration that, published in 1975, JR is more relevant than ever.

18. To wit, Gaddis again, again from The Paris Review interview, commenting on hollow, false values:

. . . I’d always been intrigued by the charade of the so-called free market, so-called free enterprise system, the stock market conceived of as what was called a “people’s capitalism” where you “owned a part of the company” and so forth. All of which is true; you own shares in a company, so you literally do own part of the assets. But if you own a hundred shares out of six or sixty or six hundred million, you’re not going to influence things very much. Also, the fact that people buy securities—the very word in this context is comic—not because they are excited by the product—often you don’t know what the company makes—but simply for profit: The stock looks good and you buy it. The moment it looks bad you sell it. What had actually happened in the company is not your concern.

19. Gaddis’s take on the “art” of capitalism: design mock ups for a potential logo for the JR Family of Companies:

20. JR is one of the most prescient novels I’ve ever read—and not just in its illustration of the the chaos at the intersection of corporatism, Wall Street, government, and military, but also in its handling and treatment of education. Gaddis is way ahead of an ugly curve, showing us an educational system largely disinterested in intellectual, aesthetic, or even athletic development. Instead we get a storehouse for children, reliant on programmed lessons delivered via technology and assessment by standardized testing. It’s ugly and it’s more real than ever now.

21. And here’s Gibb’s railing against it, in a way, in (what’s likely a half-drunken or at least hung-over) rant to his students:

Before we go any further here, has it ever occurred to any of you that all this is simply one grand misunderstanding? Since you’re not here to learn anything, but to be taught so you can pass these tests, knowledge has to be organized so it can be taught, and it has to be reduced to information so it can be organized do you follow that? In other words this leads you to assume that organization is an inherent property of the knowledge itself, and that disorder and chaos are simply irrelevant forces that threaten it from the outside. In fact it’s the opposite. Order is simply a thin, perilous condition we try to impose on the basic reality of chaos . . .

(That’s from page 20 of my Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition, by the bye).

22. There are no happy families in JR. Just broken families.

23. I said this at the top of the riff, but again–-heartbreaking.

24. This is probably a direction out of this riff—to resuscitate the emotional dimension of the novel, which is too easily overlooked, perhaps, because Gaddis’s manipulations (and all novelists manipulate their audience) require so much active participation from the reader. JR is without exposition, without the overt imposition of the novelist telling us how to feel: instead there’s a thickness to it, a building of buzz and clatter, yes, but music under all that noise: even a kernel of love (and hope!) under the heavy folds of anger.

25. Very highly recommended.

As a means of plot summary, here’s an excerpt from

As a means of plot summary, here’s an excerpt from