Origin of the Brunists is Robert Coover’s first novel. First published in 1966, this long novel tells the story of an apocalyptic religious cult that forms around the sole survivor of a mining accident. The novel begins with the Brunists prepping for the upcoming end of the world (doomsday is scheduled for the weekend). After this somewhat bewildering prologue, the novel shifts back a few months in time, to lay out the cult’s genesis, a fatal mining accident.

Origin of the Brunist’s early chapters are an engrossing and unexpectedly smooth launch into a 500+ page novel. I read the first 70 pages in one night, rapt in the weird world of West Condon, the fictional midwesternish mining town where the Brunist cult originates. I woke up the next morning and continued to read in bed. I was, and am, enthusiastic.

The second chapter of Origin of the Brunists is especially enthralling. Propulsive and engaging, the chapter zooms through the various consciousnesses of West Condon on the night of the novel’s originating disaster, the horrific mining collapse that imperils hundreds of miners. Coover inhabits the voices and minds of his characters with an easy if often grimy grace here. Evocation of consciousness has marked much of Coover’s work, from the early short story “The Brother” (1962) to his recent novel Huck Out West (2017). The man can throw his voice around. Origin of the Brunists overflows with voices. In small snatches of dialog and free-indirect speech, we get an aural and vivid picture of the miners, their children and spouses, as well as the other residents of West Condon.

The mining disaster chapter shuttles along with a filmic quality. Coover intercuts scenes of the miners escaping (or failing to escape) with a highschool basketball game, teenage lust in a parked car, and other odds and ends of West Condon life. The chapter builds in tension, reminding one of the climax of an epic movie, but one wedged unexpectedly at the narrative’s outset.

Indeed, Coover’s contest with film is something of a trademark. A signal example of this style can be found in the stories in his 1987 collection A Night at the Movies, or You Must Remember This. Stories like “The Phantom of the Movie Palace” and “Lap Dissolves” wrestle with film as a medium, deconstructing author and text, filmmakers and audiences, film reels and book pages. In the Night stories (and elsewhere, always elsewhere), Coover employs a host of metatextual techniques, dissolving one narrative into another, overlapping archetypes and synthesizing tropes, blending fables and history and commercial culture into a critique of American Pop mythology.

Coover’s metafiction always points back at its own origin, its own creation, a move that can at times take on a winking tone, a nudging elbow to the reader’s metaphorical ribs—Hey bub, see what I’m doing here? Coover’s metafictional techniques often lead him and his reader into cartoon landscapes, where postmodernly-plastic characters bounce manically off realistic contours. The best of Coover’s metafictions (like “The Babysitter,” 1969) tease their postmodern plastic into a synthesis of character, plot, and theme. However, in large doses Coover’s metafictions can tax the reader’s patience and will—the simplest example that comes to mind is “The Hat Act” (from Pricksongs & Descants, 1969), a seemingly-interminable Möbius loop that riffs on performance, trickery, and imagination. (And horniness).

I’m dwelling on Coover’s metafictional myth-making because I think of it as his calling card. And yet Origin of the Brunists bears only the faintest traces of Coover’s trademark metafictionalist moves (mostly, so far anyway, by way of its erstwhile hero, the journalist Tiger Miller). Coover’s debut reads rather as a work of highly-detailed, highly-descriptive realism, a realism that pushes its satirical edges up against the absurdity of modern American life. It reminds me very much of William Gass’s first novel Omensetter’s Luck (1966) and John Barth’s first two novels, The Floating Opera (1956) and The End of the Road (1958). (Barth heavily revised both of the novels in 1967). There’s a post-Faulknerian style here, something that can’t rightly be described as modern or postmodern. These novels distort reality without rupturing it in the way that the authors’ later works do. Later works like Barth’s Chimera (1973), Gass’s The Tunnel (1995), and Coover’s The Public Burning (1977) dismantle genre structures and tropes and rebuild them in new forms. (I might contrast here with the first novels of William Gaddis (The Recognitions, 1955), Thomas Pynchon (V., 1963), and Ishmael Reed (The Freelance Pallbearers, 1967), all of which employ postmodern and metafictional techniques right out of the gate—but that’s perhaps appropriate material for another riff).

While Origin of the Brunists doesn’t tip into Coover’s metatextual mode, it points towards his mythic style, but in a subtle, restrained way, as in this description of the moments preceding a high-school basketball game:

A ritual buzzer alerts the young athletes on the West Condon court and strikes a blurred roar from the two confronting masses of spectators. In a body, all stand. The mute patterns of run-pass-leap-thrust dissolve, congealing into two tight knots on either extremity of the court, each governed by a taut-faced dark-suited hierarch. Six young novices in black, breasts ablaze with the mark of their confession, discipline the brute roars into pulsing chants with soft loops of arm and skirt, while, at their backs, five acolytes of the invading persuasion pressed immodestly into sleek diabolic red, rattle talismans with red and white paper tails, seeking to neutralize the efficacy of the West Condon locomotive. Young peddlers circulate, selling condiments indiscriminately to all. A light oil of warm-up perspiration anoints the shoulders of the ten athletes chosen as they explode out of their respective rings to confront each other. Some of them cross themselves, some clap and cry oaths, others tweak their genitals.

These mythical touches are rare in the first section of Origin of the Brunists though. Instead, Coover seems to tease out the West Condoners’ building of their own mythology, one cobbled from the apocalyptic strands of rural American Christianity, a religion divined through signs and wonders.

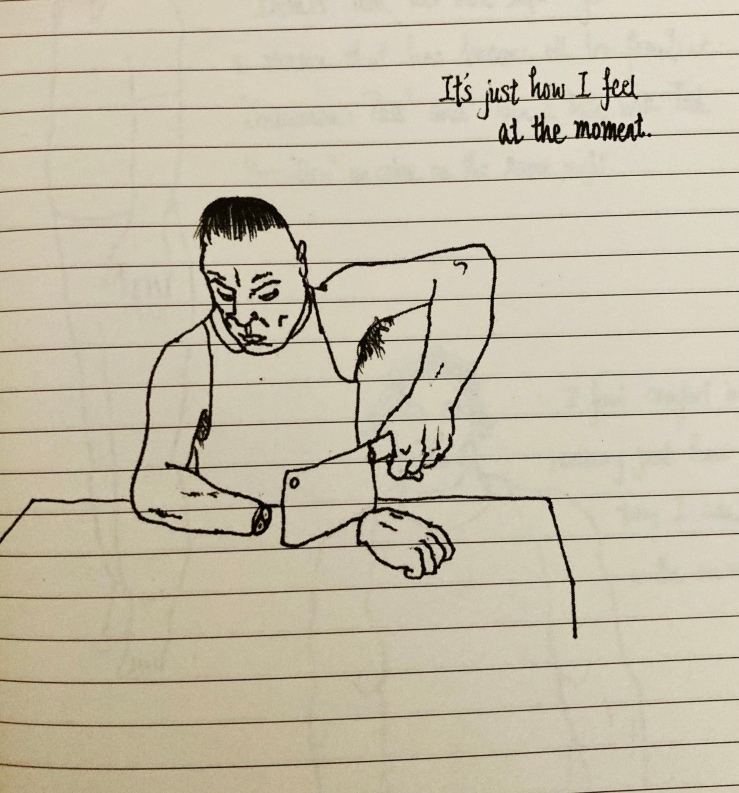

Such signs have much of their origin in Ely Collins, a miner-cum-preacher who meets his fate in the disaster. In a shocking scene that plays out with frank realism, Collins loses his leg:

“It’s okay, boys,” Collins whispered up at them. “I kin take it.” And he took to praying again.

Strelchuk lifted the ax in the air and thought: Jesus! what if I miss, I’ve never swung a goddamn ax much, what if I hit the wrong leg, or—?

“Goddamn you, Mike!” Jinx screamed, losing control. “Quit messing around! This gas is knocking me out, man! We got to get us out of here!”

And while he was screaming away like that, Strelchuk came down with the ax, caught the leg right where he aimed, true and clean, just below the knee, and the blood flew everywhere, and Juliano was crying like a goddamn baby, and Bruno, his face blood-sprayed, went dumb, mouth agape, and broke away in a silent fit, but the leg was still hooked on, they couldn’t get him free. Preach was still praying to beat hell and never even whimpered. Mike raised the ax again and drove down with all the goddamn strength he had, felt the bone this time, heard the crack, felt the sickening braking of the ax in tough tissue, and he turned and vomited. He was gagging and hacking and crying and the blood was everywhere, and still that goddamn leg was hooked on. Mario ripped away Collins’ pant leg, took the wedge he had in his pocket, pressed it up against Collins’ thigh. Strelchuk whipped off his leather belt and, using it as a tourniquet against the wedge, they stopped the heavy bleeding. Pontormo whined Italian. Strelchuk grabbed up the ax once more. His hands were greasy with blood and it was wet on his chest and face. He was afraid of missing or losing hold, and the shakes were rattling him, so he took short hacking strokes, and at last it broke off. They dragged him free. And Preacher Collins, that game old sonuvabitch, he was still praying.

I’ve quoted at such length to give a sense of Coover’s meticulousness in Origin of the Brunists. The novel is thick with life, thick with voices, mimetic detail, shapes, smells, colors, sounds. West Condon feels utterly real, making the novel’s dramatic absurdities all the more pronounced. The characters tell stories, weep and pray, bury their desires. Coover’s command of character isn’t absolute, but if his West Condoners sometimes teeter on the edge of grotesquerie they are nevertheless real, or as real as words on a page can be. More to come.

I would worry about being on such a list, because I like to write uncanonical things, things that oppose the general flow of the culture. I would certainly be happy to believe that I could share the same halls or bookcase or something with some of the writers whom I admire so much, but I would feel very insecure about my place there…I”m not sure that I want my books to be patted on the back by lots of scholars in the academy and told, “There, there, these are okay.” …My feelings about things like this are more the sort of thing I have about my children: I would be a little disturbed if everybody loved them.

I would worry about being on such a list, because I like to write uncanonical things, things that oppose the general flow of the culture. I would certainly be happy to believe that I could share the same halls or bookcase or something with some of the writers whom I admire so much, but I would feel very insecure about my place there…I”m not sure that I want my books to be patted on the back by lots of scholars in the academy and told, “There, there, these are okay.” …My feelings about things like this are more the sort of thing I have about my children: I would be a little disturbed if everybody loved them.