I first started getting a tad—just a tad—nervous about Hurricane Irma on Monday, September 4th. This was Labor Day. I had the day off from work, and it was a good day: beer, barbecue, swimming. Etc. Hurricane Irma was already enormous, a monstropolous beast for the record books looming in the Atlantic to eat up our beloved Florida.

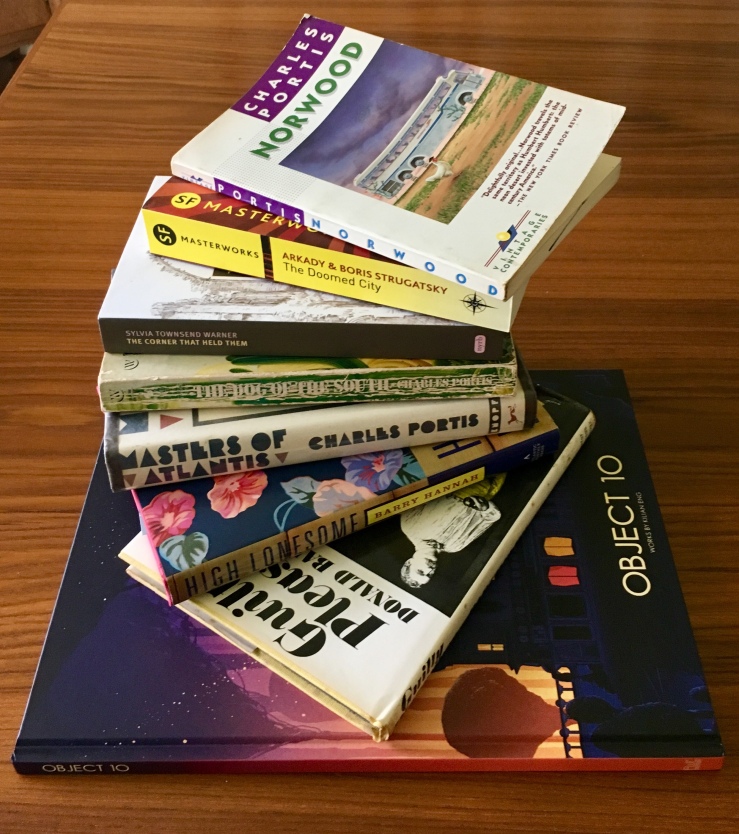

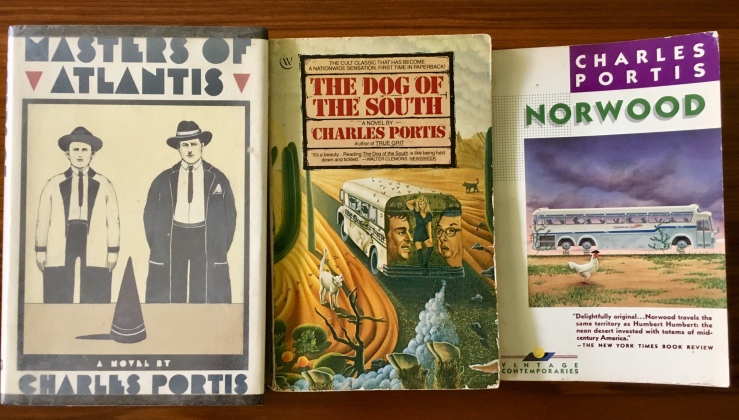

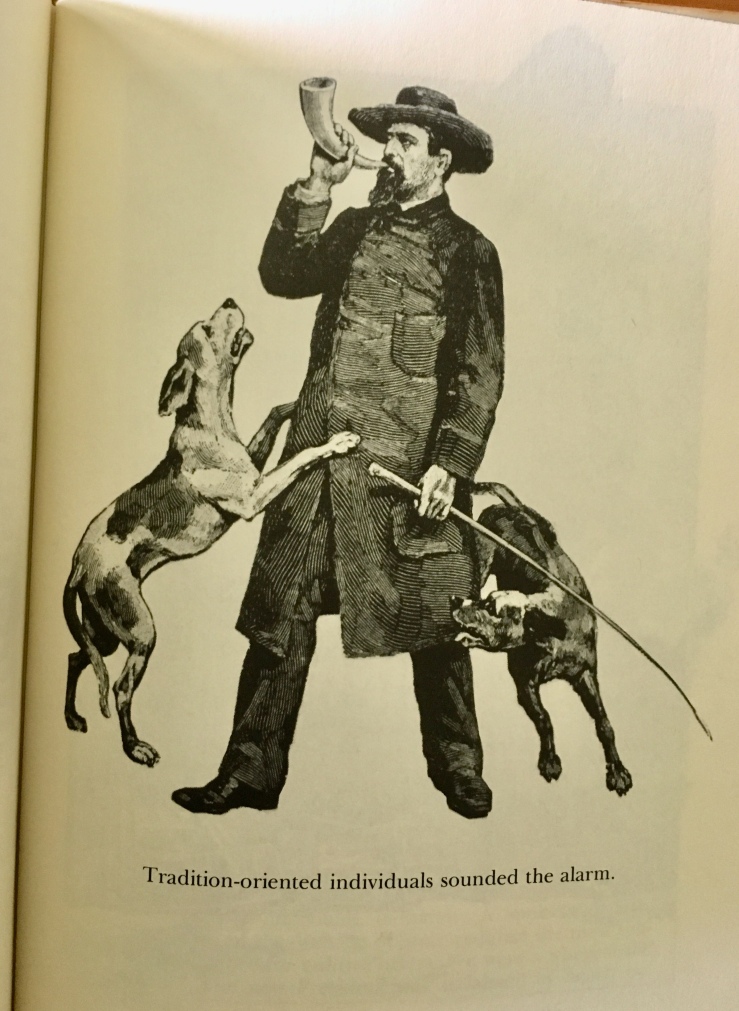

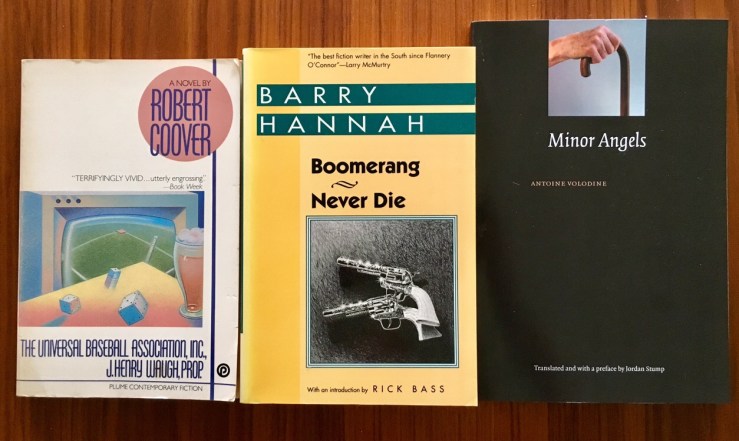

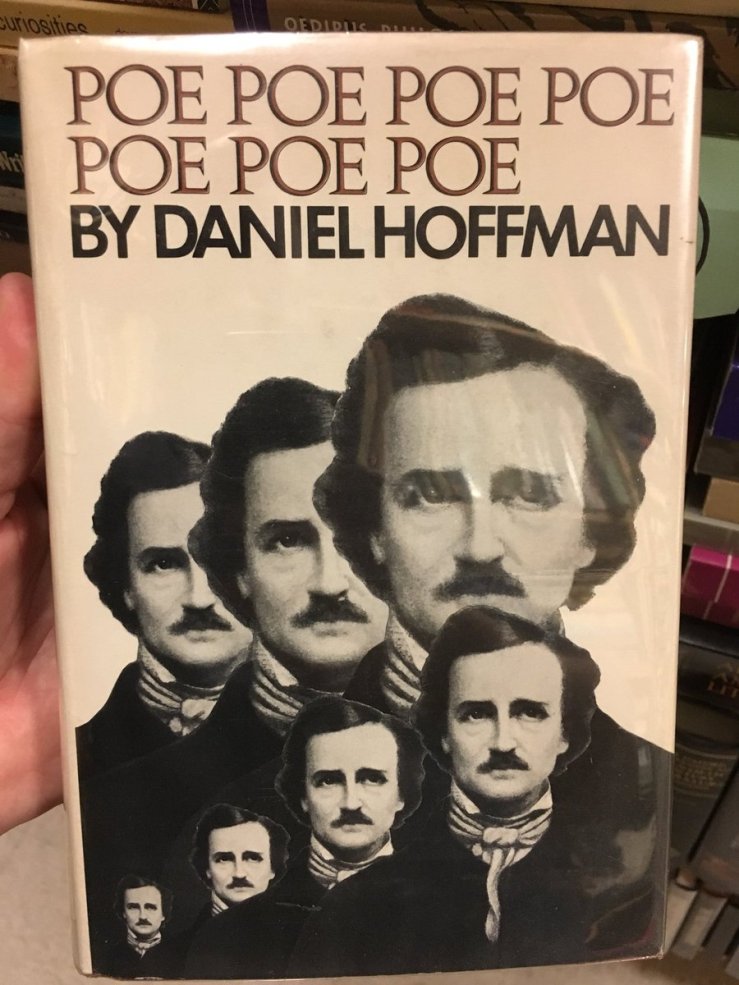

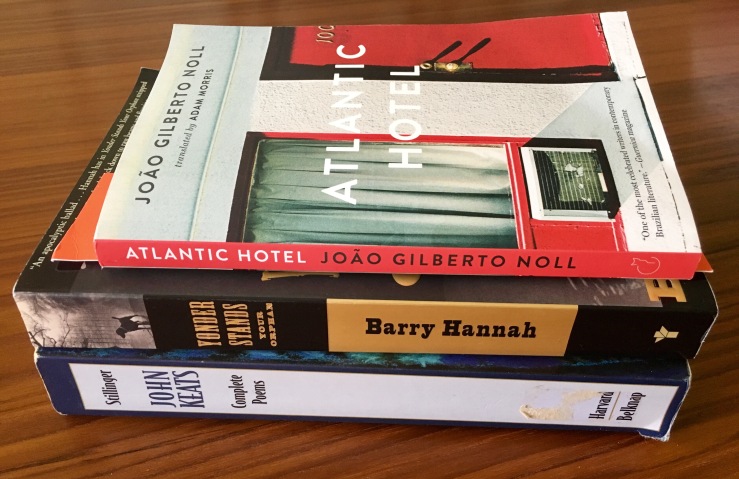

I was still reading Barry Hannah’s last novel Yonder Stands Your Orphan that day; I’d finish it up a few days later. It was excellent, full of great sentences, vignettes, riffs, rants, etc. I’d say it unraveled at the end but “unravel” implies a cohesiveness that maybe isn’t quite there—I’d have to read it again to see, and it’s worth a reread. Actually, in a sense, it coheres in that it collects a number of Hannah’s former characters into a picaresque of grotesque misadventures, hung loosely on a pimp-pornographer-outcast named Man Mortimer. Man Mortimer is the closest thing to a hero the novel has, and he’s pretty evil. Let me crib from an actual review; from Christopher Tayler’s 2001 write-up in the 2001 LRB:

The plot, such as it is, revolves around the depredations of a demonic big-city outsider called Man Mortimer, ‘a gambler, a liaison for stolen cars and a runner of whores, including three Vicksburg housewives’. Mortimer starts to take an interest in cutting people when he finds out that his sort-of girlfriend, Dee Allison – a single mother, nurse and ‘nun of apathy’ – has been unfaithful to him. Dee’s feral twin sons, meanwhile, find in a dried-up sinkhole a car containing the skeletons of Mortimer’s former lover and her child; they clean the skeletons up and take to carting them round the woods. Mortimer is initially concerned with avenging himself on Dee and reclaiming the evidence, but he soon graduates to fairly random attacks on all who cross his path – all, that is, except the poisonous Sidney Farté, who is delighted when Mortimer chops his father’s head off and replaces it with a football, since this speeds his inheritance of the family bait store.

Yonder Stands Your Orphan is often surreal and always dark; it often reminded me of David Lynch’s crime stories, with their grotesque gangsters and abject phantoms. Hell, there’s even a character named Frank Booth.

But where was I? Sorry. This riff is in part a way for me to collect the past few days into something coherent, to figure out what day it is, to prevent an unraveling. Yes, I was nervous on Labor Day, a tad. I had made a list at the beginning of that weekend of five items, chores, I mean, of which I’d accomplished four, including Clean gutters and roof. I did not complete the item I had listed as Hurricane audit.

I picked up a few flats of bottled water before my first class on Tuesday, September 5th. The shelves were already looking bare. I stopped by a Walmart and then a Lowe’s on the way home, failing to get a second gas can. Other people were starting to get a tad nervous. (Nervousness spreads like an infection).

By September 6th, it was nigh impossible to buy a generator in Jacksonville or any of its satellite cities. The college where I teach closed on Thursday, September 7th; my kids’ school closed. Everything started shutting down. There were lots of texts and calls between friends and family, basically amounting to, Should I stay or should I go? Back up plans, hotel reservations to hopefully cancel, etc.

I managed to get a generator on September 8th, which I’d crank up two days later. At this point it seemed clear, or relatively clear, that we were staying, and that family from Tampa Bay would be staying with us. September 8th was long: Trimming back suspicious branches, securing loose items from around the house’s perimeter, busting up an old playhouse that my kids really didn’t play on any more. Cooking meals that could be reheated on a grill. Rehashing plans, piling up supplies. Etc.

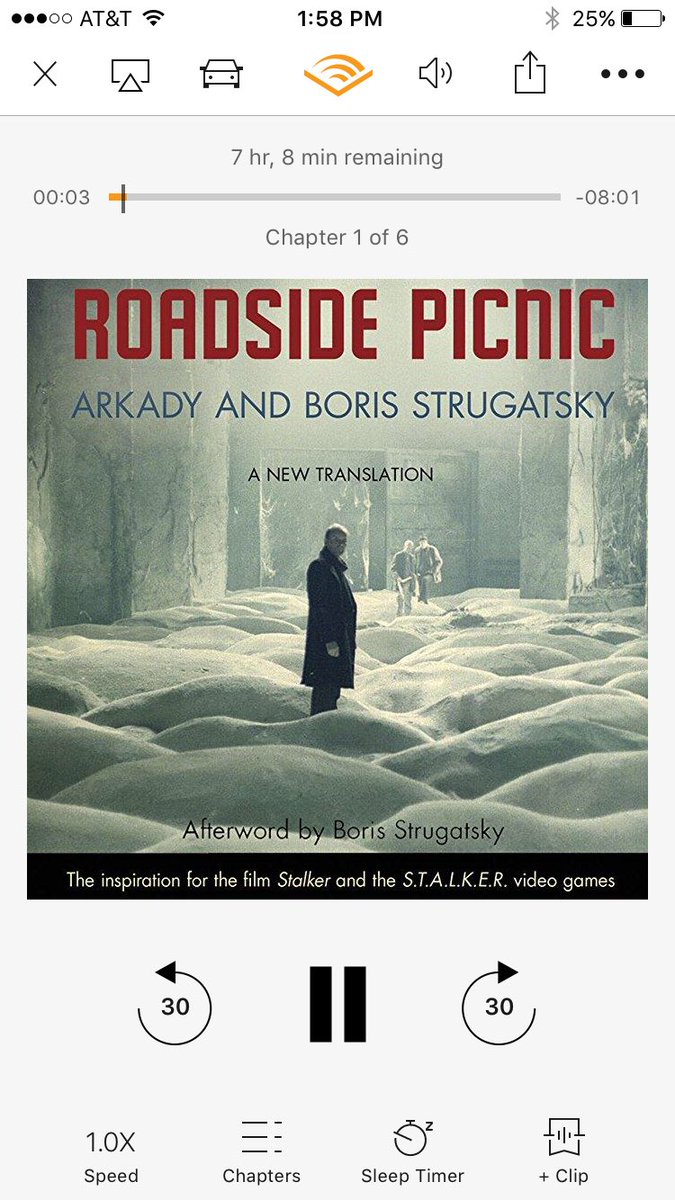

I finally got tired of listening to the radio (scaring the hell out of me) during this hurricane prep, and picked up the audiobook of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic, translated by Olena Bormashenko, and read by Robert Forster. I basically listened to each chapter twice over the next few days. The translation is inspiring—witty and raw, noir and smart, and Robert Forster’s narration is perfect—wry, dry, sad, and profound. I need to rewatch Tarkovsky’s Stalker now. I’m a bit ashamed that I haven’t read this one before, and I found its final moments especially moving (exhausted as I was). Highly recommended.

My evacuees arrived early September 9th. The next few days are a soggy blur. A nor’easter saturated northeast Florida; the St. Johns River was already, like, full, and the peninsula I live on (a peninsula on a peninsula), was loose. Like, not firm. Irma’s big bands started hitting the First Coast with a frank sincerity. We watched the local NFL team beat Houston’s team. There’s no symbolism or irony there. I was alternating vodka with coffee with green tea. Two twin pines lord over my house, one in the back, one in the front, maybe five decades old. They swayed and swayed, pelting fresh green pine cones onto the roof for the next 24 hours or so with an admirable consistency. By 10pm Sunday night I realized that I wouldn’t be able to sleep. We lost electrical power, put the kids to bed. Branches started coming down, thudding with scary force, kick drums for the pine cones’ tight snare raps. Limbs like something heavier, thick bass notes. How did the kids sleep through it all?

By candlelight, I read the first 66 pages of João Gilberto Noll’s novella Atlantic Hotel (English translation by Adam Morris) at some point that night. Atlantic Hotel is a picaresque nightmare, one weird horror turning into another. In a way, it was perfect reading for Irma’s approach, ominous and eerie. I also don’t know how much I registered, as I kept going out in the hard wind and slanted thick rain to put a big flashlight on my backyard, where the water kept creeping up and up, eventually getting too high for my gumboot but thankfully never spilling into my house. The feeling of reading Atlantic Hotel registered—the tone, the mood, the rhythm—but not the plot or the anonymous lead character. I’ll have to hit Reset on it.

By 3:00am the brunt of the storm cascaded over my own personal house (yes); the pine cones hailed down in a rhythm like hard rain, punctuated by larger crashes of pine limbs and other debris. For unreasonable reasons I will never know, I pulled out Keats and read Lamia with a bigass flashlight. The storm band somewhat subsided; I rested my eyes for an hour or two, then the whole thing commenced again. By nine in the morning it seemed the worst of the storm had passed, and I slept. Lamia snaked into my dreams, coiled into Irma. My son woke me up at 10:30am—a house down the street was on fire. Some asshole had cranked his generator in his garage—his closed garage!—next to his gas cans and propane tank and car. The garage burned; the car exploded, along with the other car in the driveway.

That Sunday, September 11th saw historic flooding in the urban core of Jacksonville. My kids’ school, about a third of a mile from my house, flooded. While trudging around in the late afternoon in our gumboots, happy to be free of our sweltering house for a bit, we saw two teams of Army Rangers paddle up a canal, onto the street, there to evacuate stranded old folks. Surreal. Word traveled about other locations underwater—a flooded Publix, a ruined boatyard, Memorial Park a lake. The worst rumor, to me anyway, was that my beloved used bookstore, Chamblin Bookmine, was underwater. I still can’t bring myself to go over there. I know where it is and how high the water got.

These past few days, I listened to my favorite audiobook during much of the cleanup—Richard Poe’s recording of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. What a strange awful comfort. A tree fell on my carport and shed, but they held, sorta. My lawn is a stinking mess, the blazing sun pulling out the water in humid reeking waves. The squelch of it all is something damn else. The pine trees dropped plenty of enormous limbs, but none did real damage. Up on the roof yesterday, clearing one off, I shuddered at its size and weight. I shuddered because of course It could have been so much worse. I’m thankful.

year ago. He was kind of

year ago. He was kind of