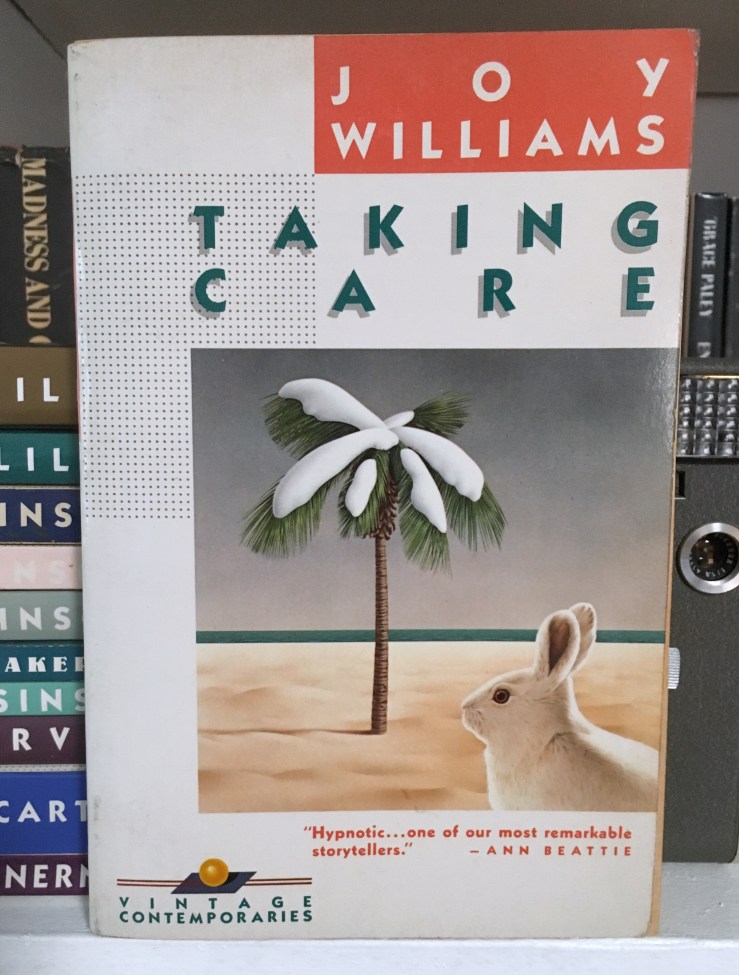

Let’s begin with a paragraph from Joy Williams’ story “Winter Chemistry.” Let’s begin with this paragraph because I think it makes a better argument for reading Joy Williams’ story “Winter Chemistry” than I ever could. Here’s the paragraph:

Judy Cushman and Julep Lee had become friends the summer before when they were on the beach. It was a bitter, shining Maine day and they were alone except for two people drowning just beyond the breaker line. The two girls sat on the beach, eating potato chips, unable to decide if the people were drowning or if they were just having a good time. Even after they disappeared, the girls could not believe they had really done it. They went home and the next day read about it in the newspapers. From that day on, they spent all their time together, even though they never mentioned the incident again.

The paragraph is a perfect little short story on its own, the second part of its second sentence deployed in a simple, casually devastating manner (“they were alone except for two people drowning just beyond the breaker line”). There’s a wonderful ambiguity to the whole passage, an ambiguity most resonant in the second “they” of the fourth sentence—what is the referent of that “they”? The drowned victims? Or the girls who witnessed the drowning, inert, snacking?

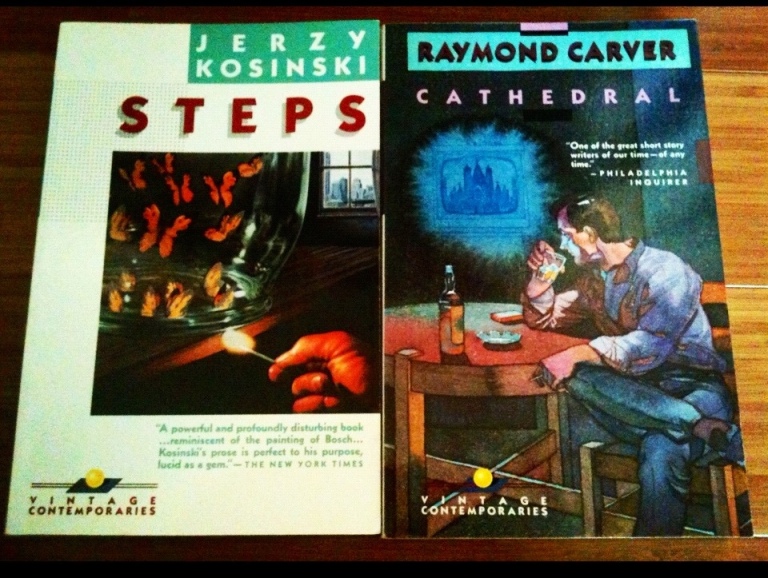

Stripes of ambiguity like this one run throughout the sixteen stories in Joy Williams’ 1982 debut collection Taking Care. Williams’ characters—often young girls or young women—cannot quite fit what they immediately perceive into a coherent schema of the phenomenological world.

In the opening story, “The Lover,” for instance, Williams portrays a woman dissociating, told in a present-tense, free indirect style that trips into our hero’s troubled mind:

The girl wants to be in love. Her face is thin with the thinness of a failed lover. It is so difficult! Love is concentration, she feels, but she can remember nothing. She tries to recollect two things a day. In the morning with her coffee, she tries to remember and in the evening, with her first bourbon and water, she tries to remember as well. She has been trying to remember the birth of her child now for several days. Nothing returns to her. Life is so intrusive! Everyone was talking. There was too much conversation! … The girl wished that they would stop talking. She wished that they would turn the radio on instead and be still. The baby inside her was hard and glossy as an ear of corn. She wanted to say something witty or charming so that they would know she was fine and would stop talking. While she was thinking of something perfectly balanced and amusing to say, the baby was born.

There are over a dozen exclamation marks in “The Lover,” deployed in artful disregard for the conventional creative writing advice that eschews using those pointed poles. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a story use exclamation marks so effectively: “There was too much conversation!” Williams evokes her character’s emerging anxiety as it tips close to mania. We never discover a cause for her dissociation and neither does she. We get only the fallout, the effects, sentences piling together without a clear destination other than dissociation. She tries to find some kind of an answer, calling up an AM radio show called Action Line to talk to the Answer Man:

The girl goes to the telephone and dials hurriedly. It is very late. She whispers, not wanting to wake the child. There is static and humming. “I can’t make you out,” the Answer Man shouts. “Are you a phronemophobiac?” The girl says more firmly, “I want to know my hour.” “Your hour came, dear,” he says. “It went when you were sleeping. It came and saw you dreaming and it went back to where it was.”

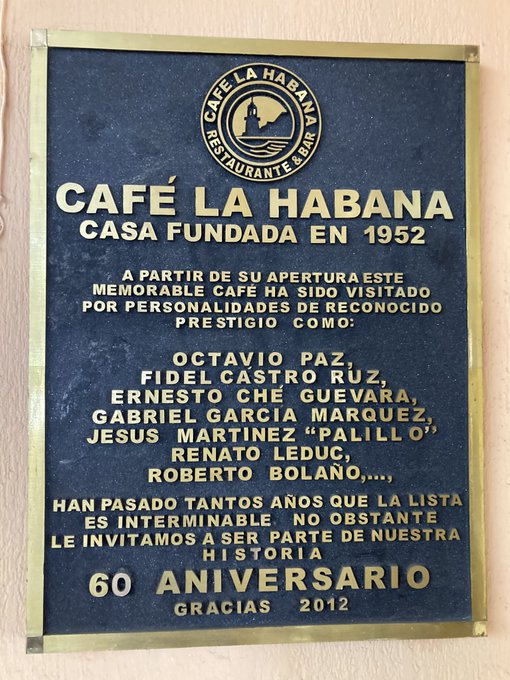

A later story in Taking Care, “The Excursion,” returns to the themes of dissociation we saw in “The Lover.” In “The Excursion,” a girl named Jenny is unstuck in time. Her consciousness reels between childhood and adulthood; memories of her parents compound with adult experiences with her lover in Mexico. The result is startling, disorienting, and often upsetting. (And again, Williams deploys her exclamation marks like artful verbal pricks).

“The Lover” and “The Excursion” are probably the two most formally-daring stories in Taking Care, but their ambiguous spirit is part and parcel of the collection as a whole. Consider “Shorelines,” a rare first-person perspective story, which begins with the narrator trying to set order where there is none:

I want to explain. There are only the two of us, the child and me. I sleep alone. Jace is gone. My hair is wavy, my posture good. I drink a little. Food bores me. It takes so long to eat. Being honest, I must say I drink. I drink, perhaps, more than moderately, but that is why there is so much milk. I have a terrible thirst. Rum and Coke. Grocery wine. Anything that cools. Gin and juices of all sorts. My breasts are always aching, particularly the left, the earnest one, which the baby refuses to favor. First comforts must be learned, I suppose. It’s a matter of exposure.

“I want to explain,” our unnamed narrator declares, but her mind seems to wander away from this mission almost immediately. Who is Jace, and where has he gone? We never really find out, but we do get puzzling, upsetting clues, like this one:

It has always been Jace only. We were children together. We lived in the same house. It was a big house on the water. Jace remembers it precisely. I remember it not as well. There were eleven people in that house and a dog beneath it, tied night and day to the pilings. Eleven of us and always a baby. It doesn’t seem reasonable now when I think on it, but there were always eleven of us and always a baby. The diapers and the tiny clothes, hanging out to dry, for years!

Is Jace the father of the baby? Is he the narrator’s brother? The tingling ambiguities remain as the story concludes, the narrator still waiting on a return that may or may not happen.

What makes Williams’ ambiguities resonate so strongly is her precise evocation of place. Her stories happen in real physical space, the concrete details of which often contrast strongly with her character’s abstracted consciousnesses. “Shorelines” is one of several Florida stories in the collection, and Williams writes authoritatively about the Sunshine State without devolving into the caricature or grotesquerie that pervades so much writing about Florida. (As a Floridian, nothing annoys me quite so much in fiction as certain writers’ tendencies to exoticize Florida).

“Shepherd” is another of Wiliams’ Florida stories. (And one of her dog stories. And grief stories. And unnamed-girl-hero stories). It is set in the Florida Keys, where Williams lived for some time—her early career was in doing research for the U.S. Navy Marine Laboratory in Siesta Key, Florida. (Williams’ best-selling book is actually a history and tour guide of the Florida Keys). “Shepherd” is a sad story, one of the most basic stories in literature, really: Your dog dies. The story is ultimately about perception. After the dog’s death, the girl’s boyfriend cannot comprehend her grief. He scolds her:

“I think you’re wonderful, but I think a little realism is in order here. You would stand and scream at that dog, darling.” …

“I wasn’t screaming,” she said. The dog had a famous trick. The girl would ask, “Do you love me?” and he would leap up, all fours, into her arms. Everyone had been amazed.

While most readers will sympathize with the girl, her boyfriend’s perspective introduces an unsettling ambiguity. And yet Williams, or at least her character, resolves some of this ambiguity in what I take to be the story’s thesis:

Silence was a thing entrusted to the animals, the girl thought. Many things that human words have harmed are restored again by the silence of animals.

Taking Care is a bipolar book. Florida is one of its poles. Maine, where Williams grew up, is the other. “Winter Chemistry” (originally published in a different version as “A Story about Friends”) is a Maine story. In “Winter Chemistry,” two teenage girls, bored, play at something they don’t have the language for yet. Their game entails spying on their chemistry teacher, whom they both maybe are in love with. The girls may not comprehend what their emerging sexuality entails, but they do feel the physical world. Consider Williams’ evocation of Maine’s winter:

The cold didn’t invent anything like the summer has a habit of doing and it didn’t disclose anything like the spring. It lay powerfully encamped—waiting, altering one’s ambitions, encouraging ends. The cold made for an ache, a restlessness and an irritation, and thinking that fell in odd and unemployable directions.

The story propels the aching duo in “odd and unemployable directions” — and towards an unexpected violence foreshadowed earlier in the summer, as the two munched chips on the beach, watching a pair of swimmers drown.

In “Train,” Williams gives us another pair of girls, Danica and Jane. They are traveling from Maine to Florida, traversing the poles of Williams’ Taking Care. They explore “the entire train, from north to south” and find most of the adults drunk, or at least getting there. Jane’s parents, the Muirheads, clearly, strongly, definitively out of love, are in a fight. The adult world’s authority is always under suspicion in Taking Care. And yet the adults in Williams’ stories see what the children cannot yet see:

“Do you think Jane and I will be friends forever?” Dan asked.

Mr. Muirhead looked surprised. “Definitely not. Jane will not have friends. Jane will have husbands, enemies and lawyers.” He cracked ice noisily with his white teeth. “I’m glad you enjoyed your summer, Dan, and I hope you’re enjoying your childhood. When you grow up, a shadow falls. Everything’s sunny and then this big Goddamn wing or something passes overhead.”

“Oh,” Dan said.

In another Maine story, “Escapes,” a little girl named Lizzie comes to realize the scope of her mother’s alcoholism after the mother breaks down during a magician’s act. (As I type it out, this premise sounds far zanier than it reads in the book). Lizzie’s final awful epiphany is still coded in ambiguity though:

I had never seen my mother sleeping and I watched her as she must once have watched me, as everyone watches a sleeping thing, not knowing how it would turn out or when. then slowly I began to eat the donut with my mittened hands. The sour hair of the wool mingled with the tasteless crumbs and this utterly absorbed my attention. I pretended someone was feeding me.

Lizzie, like many of the characters in Taking Care, is realizing that she will have to take care of herself.

The theme of caretaking evinces most strongly in the titular story. “Taking Care” seems to be set in Maine, although it’s not entirely clear. The story focuses on “Jones, the preacher,” who “has been in love all his life”; indeed, “Jones’s love is much too apparent and it arouses neglect.” Jones takes care of himself only so that he can take care of others. His wife is diagnosed with cancer; his daughter, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, has run away to Mexico, leaving Jones to care for her infant daughter, his only grandchild. The story is devastating in its evocation of love and duty, and ends although its ending is ambiguous, it nevertheless concludes on an achingly-sweet grace note.

Jones’s enduring, patient love is unusual in Taking Care, where friendships splinter, marriages fail, and children realize their parents’ vices and frailties might be their true inheritance. These are stories of domestic doom and incipient madness, alcoholism and lost pets. There’s humor here, but the humor is ice dry, and never applied as even a palliative to the central sadness of Taking Care. Williams’ humor is something closer to cosmic absurdity, a recognition of the ambiguity at the core of being human, of not knowing. It’s the humor of two girls eating chips on a beach, unable to decide if the people they are gazing at are drowning or just having a good time.

I enjoyed many of the stories in “Taking Care” very much, and especially enjoyed the stranger, more formally-adventurous ones, like “The Lover” and “The Excursion.” I look forward to reading more of Joy Williams’ work. Highly recommended.

year ago. He was kind of

year ago. He was kind of