Trans-Atlantyk by Witold Gombrowicz. English translation by Carolyn French and Nina Karsov. Trade paperback by Yale University Press, 1994. Cover design by Lorenzo Ottaviani. I reviewed Trans-Atlantyk here.

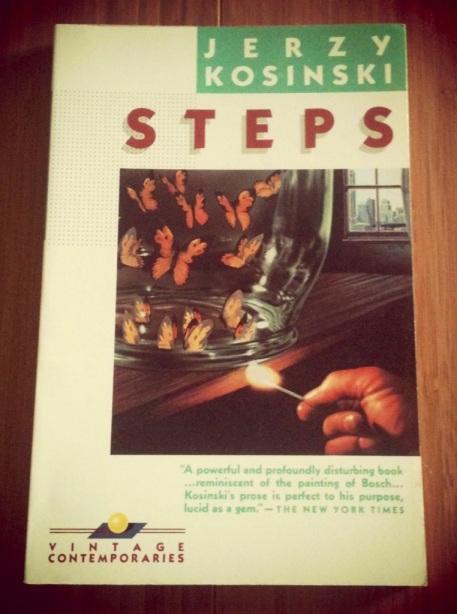

Steps by Jerzy Kosinski. Another Vintage Contemporaries edition, 1988. Cover design by Lorraine Louie; illustration by Chris Moore.

The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll by Álvaro Mutis. English translation by Edith Grossman. NYRB, 2002. Cover design by Katy Homans; cover photograph by Sally Mann.

Biblioklept reviews here, here, and here.

These three books may or may not be cult novels.

I’ve been thinking a bit about the term cult novel, a term which used to fascinate me in my twenties, but one which I’m beginning to suspect doesn’t really mean anything, or seems to have a different value, anyway, now.

I’ve been thinking about cult novels because I’m nearing the end of Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s excellent excellent excellent 1958 novel The Leopard, which someone somewhere (who? where?) told me was a cult novel. I have no idea why The Leopard should be a cult novel. Where is its cult? By cult do we just mean “underread” or “underappreciated”?

It seems that the internet has dramatically changed what a cult novel might be/mean. (I wrote a bit about cult novels on this blog years ago, and I would expand the rough list I outlined were I to update that lousy post, which I won’t). The three books I picked today might be cult novels in the sense that they might be underappreciated/underread—although that statement strikes me as absurd somehow! (Steps won the National Book Award).

I guess a real cult novel would be a novel, or perhaps author, who inspires a cultishly devoted base of readers (is this what the kids call a fandom? Jesus Christ). And because of the internet, cults can be big now: Pynchon, Ballard, Cormac McCarthy, David Foster Wallace, Philip K. Dick. Such writers and their novels have inspired obsessive fans. But the works of these novelists are hardly samizdat. Look at PK Dick—think of how much of his work, his writing, his ideas have seeped into mainstream culture? So is it cult then?

Or am I really just stuck on an older connotation of “cult,” of cult classic, I guess, which was just a way of saying odd + underappreciated + hard to find? Which is to say in modes both literal and figurative: Inaccessible.

And so well then when I say that the internet has changed what a cult novel is/isn’t, I suppose I’m simply noting access—access to the material books, access to fellow readers, access to forums, access to analysis, etc. And I suppose that’s, uh, good.

I considered hammering out a list of cult novels here at the end of this pointless little riff, but it would be too long. Besides, I really have no idea what a cult novel is anymore. I threw the question out there on Twitter, asking for examples, and got a wonderful wild range of responses, but the best response came almost immediately:

Hurrah for more intense pocket universes than ever before.