I read very few contemporary books, especially contemporary novels. This reluctance to read contemporary literature isn’t a rule as much as it is a necessity born from the human limitations of my time and the fact that I am a slow reader. (I’ll also admit to a certain wariness towards trends coupled with an antipathy toward publishing hype. (I’m sure many readers detest the trendy/hype couple, as do I. (I’m sure some readers think I use this blog to hype/trend. Forgive me; it’s not my intention. I’m enthusiastic at times.)))

I have no idea what the best books of 2019 are. Maybe I’ll know in 2039 or 2049 or 2079 (when I’ll be a magical one hundred years old).

I’ve been doing these Three Books posts on and off for a few years. They give me something to do on a Sunday, except when I have something to do on a Sunday, in which case, I don’t do them. There are two more Sundays in 2019 and I figured I’d do a Three Books post about the books published this year that I enjoyed most this year. A few jumped readily to mind, including books that were translated or republished in new editions this year, like João Gilberto Noll’s short novel Lord, or Sylvia Townsend Warner’s The Corner That Held Them, or Ann Quin’s 1964 novel Berg. But new editions or new/first translations isn’t exactly “2019” is it? Or is it? I mean, these were published in 2019?

Just add them to the list anyway.

And add Anna Burns’ maybe-horror/maybe-comedy novel Milkman to the list, even though it was published in 2018.

And add Anna Kavan’s definitely-horror/definitely-sci-fi novel Ice to the list, even though it was re–published in 2018, a fiftieth anniversary edition. (It’s not a new book, right? New to me though.)

Ann Quin, Anna Burns, Anna Kavan…how about Anne Boyer? For me, 2019 was a variation on Annas, I guess.

The Undying by Anne Boyer. 2019 first edition hardback from FS&G. Jacket design by Srick&Williams; jacket art by Mykola Davydenko.

This is a wonderfully angry, discursive, recursive book: literary biography, literary criticism, art history, art criticism, Foucault, John Donne, Susan Sontag, Lucretius, Virginia Woolf; a howl at the hoaxers, frauds, self-helperists and their pinkwashed platitudes. And lots of pain, expressed with sentiment that bears no trace of sentimentality.

Boyer’s aphoristic style is engrossing. Her paragraphs and one-liners bear a ludic stamp seemingly at odds with her subject matter. The work of the writing, the heavy burden of smithing those sentences is all but elided—instead we get the clarity of a focused mind drawing together seemingly-disparate threads into a cohesive and compelling memoir that transcends the personal without necessarily meaning to.

Showing is a betrayal of the real, which you can never quite know with your eyes in the first place, and if you are trying to survive for the purpose of literature, showing and not telling is reason enough to endure the disabling processes required for staying alive.

Thank you again to BLCKDGRD for sending me this strange angry beautiful book.

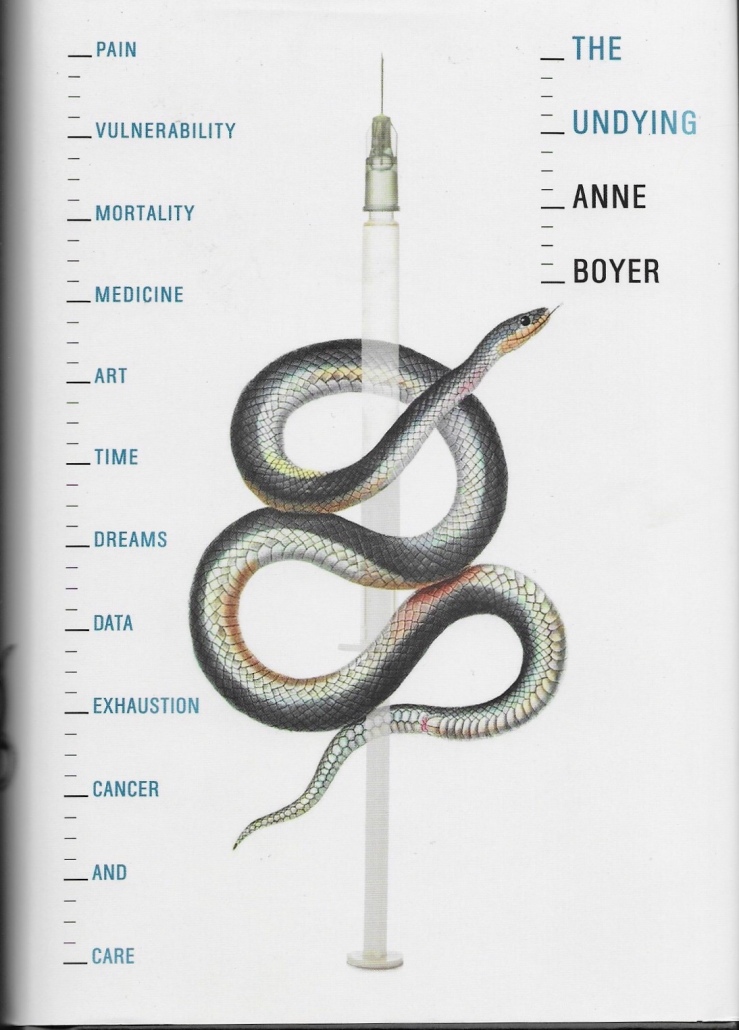

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James. 2019 first edition hardback from Random House. Jacket design by Helen Yentus; jack illustration by Pablo Gerardo Camacho.

I wrote a review of Black Leopard, Red Wolf that I titled “Marlon James’s Black Leopard, Red Wolf is a postmodern fantasy novel that challenges the conventions of storytelling itself.”

Black Leopard, Red Wolf makes me think of that trend/hype problem I mentioned above—novels that get hyped, novels that seem trendy (“It’s Game of Thrones in a medieval mythical Africa!”) and then maybe not read. I think a lot of people read BL/RW though, and many found it Not to Their Taste, which, fine. I loved. it. From my review:

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is clearly Not for Everybody. It’s violent and strange, and the sex in it will likely upset conservative readers. It’s also shaggy and unwieldy. It probably has a future as a cult novel. You just sort of have to go with its fluid (in every sense of that word) program and enjoy the ride. I enjoyed it very much and am looking forward to the sequel.

Rusty Brown by Chris Ware. 2019 first edition hardback from Pantheon. No cover designer or artist credited, but the work is unquestionably Ware’s.

A masterpiece. I reviewed it for The Comics Journal, stating that,

Rusty Brown is a sprawling story about memory and perception, about minor triumphs and chronic failures, about how our inner monologues might not match up to the reality around us. In Ware’s world, life can be blurry, spotty, fragmented. His characters are so bound up in their own consciousnesses that they cannot see the bigger picture that frames them.

Rusty Brown is only the first part of (what I understand to be) a two-part novel. It took Ware eighteen years to finish. Maybe we’ll know in 2037 if it was in fact a really great important best favorite novel of 2019. Or maybe not.

But I love it now, and I loved these books this year.