From the top down:

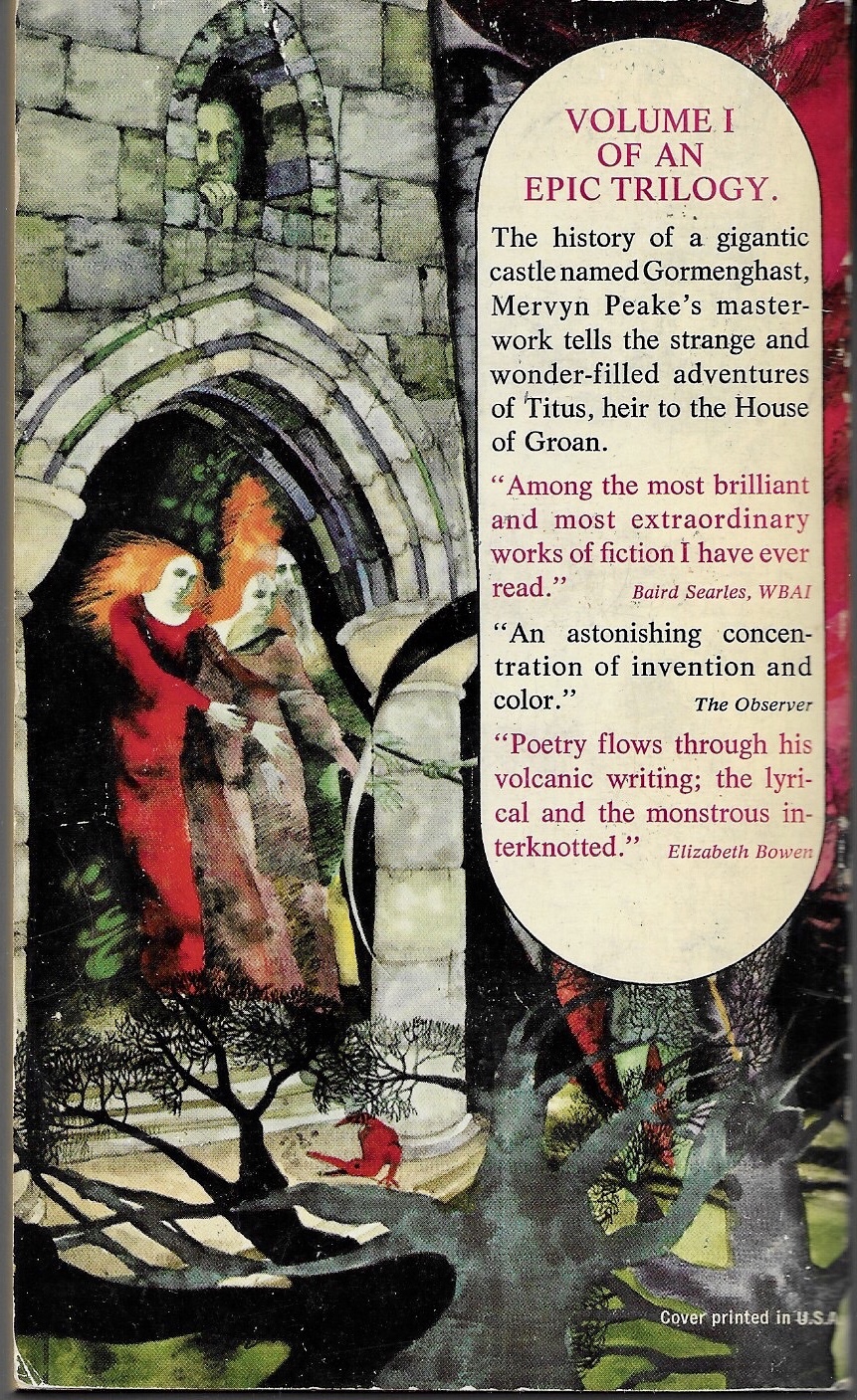

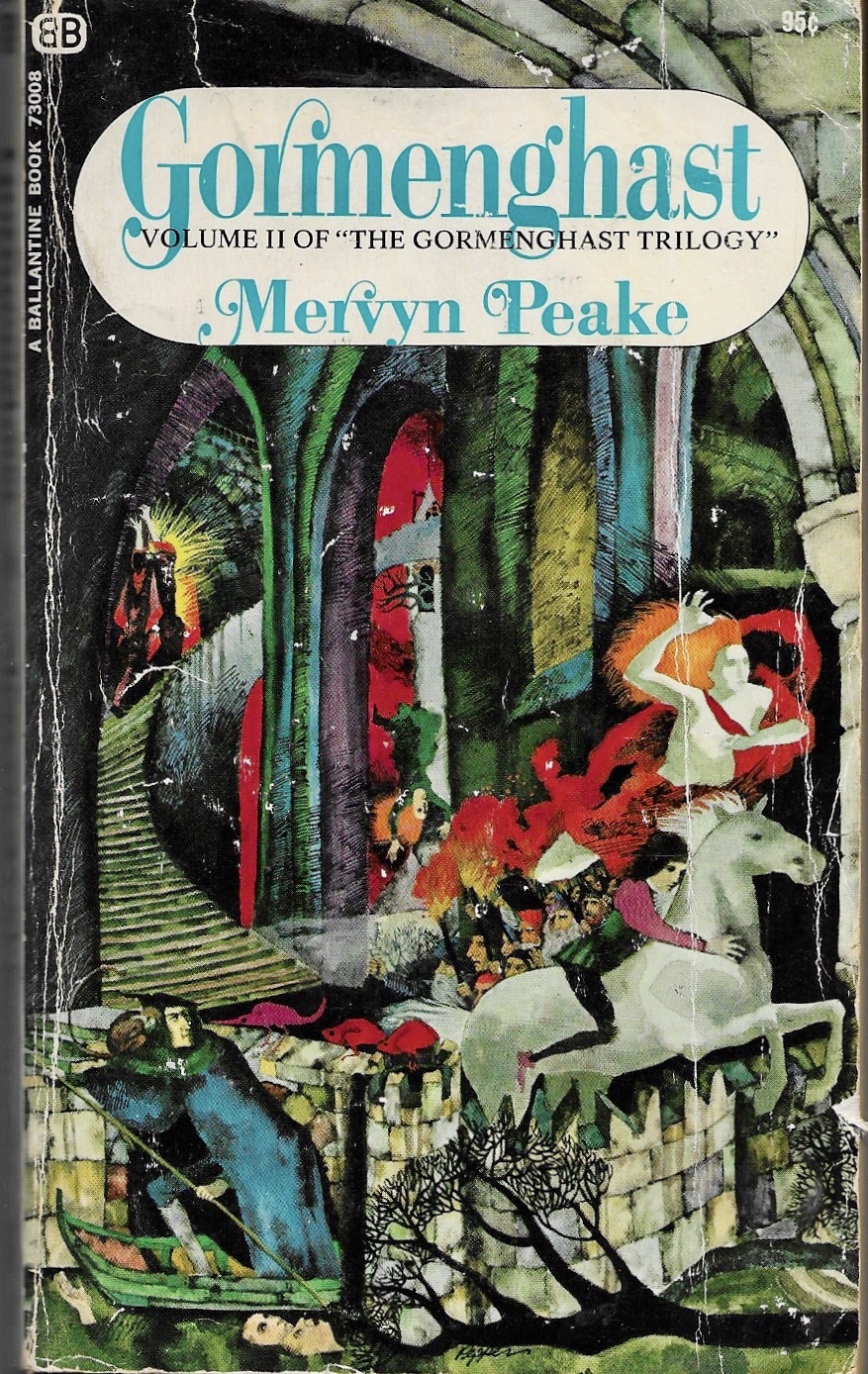

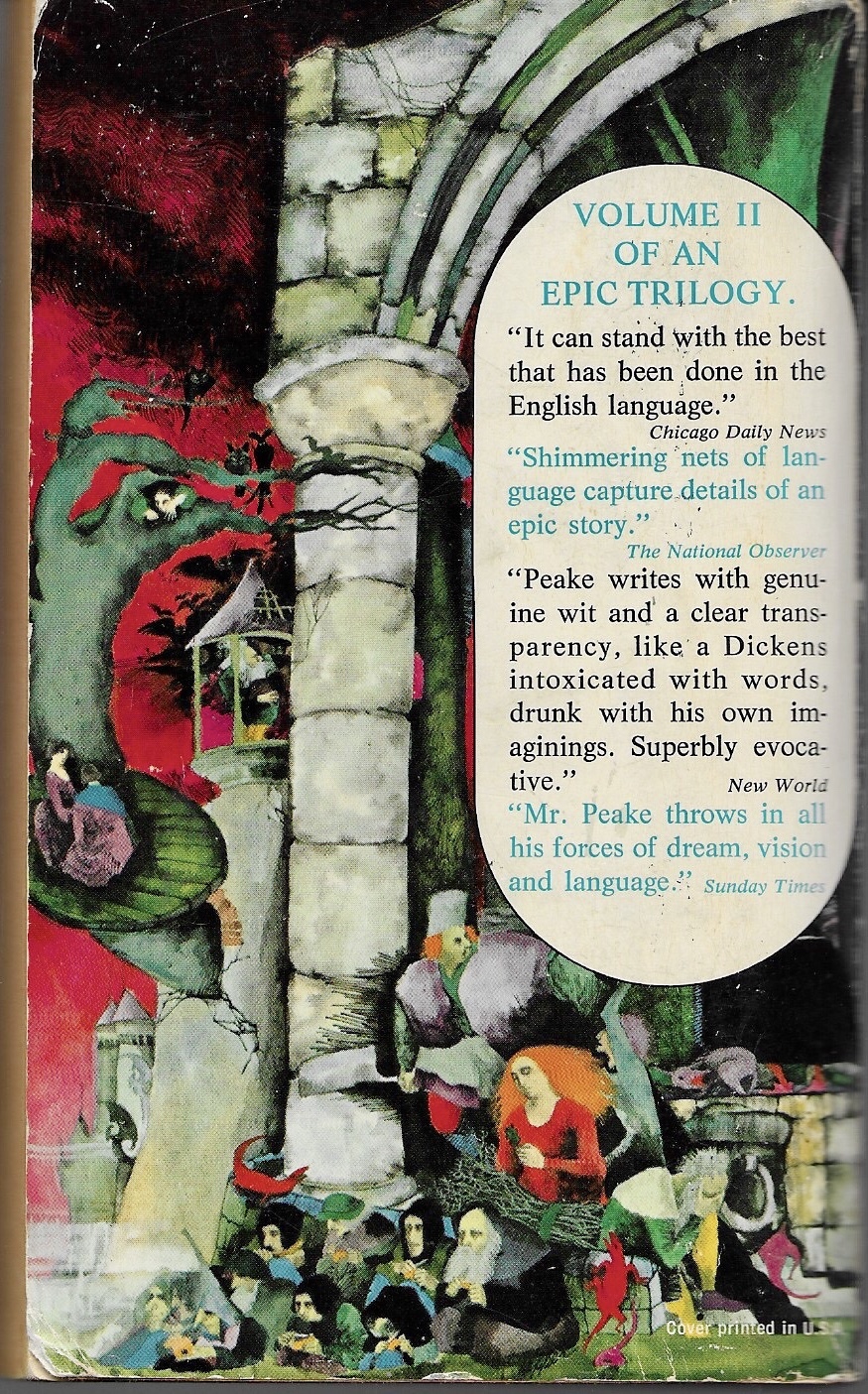

I came across a battered and beautiful copy of Mervyn Peake’s novel Gormenghast by chance a few weeks ago and asked Twitter if the trilogy was any good. The answer was a very enthusiastic, even cultish Yes. I still can’t believe I’d never even heard of Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy until recently—I grew up reading fantasy novels, and Lord of the Rings, the novel that Peake’s trilogy is often compared to, is and was one of my favorite novels of all time. The comparisons to Tolkien though aren’t particularly convincing, beyond the time period the novels were published, and their both being trilogies. Peake’s novels are grungier, wordier, thicker somehow; he plasters word on word on word building a baroque and grotesque world that is rich and full yet nevertheless opaque. He refuses to explain, but he shows. I read Titus Groan, the first novel in the trilogy, in a bit of a fever, feeding on its thickness. It reminded me of Dickens and T.H. White, but also Leonardo’s grotesque caricatures and Aleksei German’s film adaptation of Hard to Be a God. So much abjection! I have failed to discuss the plot: It’s a castle plot, whatever that means. There are insiders and outsiders. An outsider is trying to make his way not just in but also up: That’s Steerpike, the villainous hero of Titus Groan, and Iago-like intellect whose machinations Peake doesn’t just tell us about, but actually harnesses for us to ride around after. Little Titus Groan barely shows up in his eponymous volume, but so far in Gormenghast there’s been a lot more of him, which is cool, even if there’s been less Steerpike so far, which is not so cool. I’m about halfway through and really enjoying it. The novel vacillates between tones, dwelling just a bit-too-long on a bathetic romance before whirling again to other matters: a feral child, assassinations, an exiled retainer in the wild. Great stuff. The books are illustrated by the author:

Peake’s Gormenghast books have been my “big” read so far this year, but I’ve slipped in other texts too of course. Dmitry Samarov’s Music to My Eyes is a sort of love-letter (“love” is maybe not the right word) to the Chicago music scene; it also functions as a memoir of sorts. The vignettes and short essays make for quick and entertaining reads. The book is also illustrated by the author; here is his picture of David Berman:

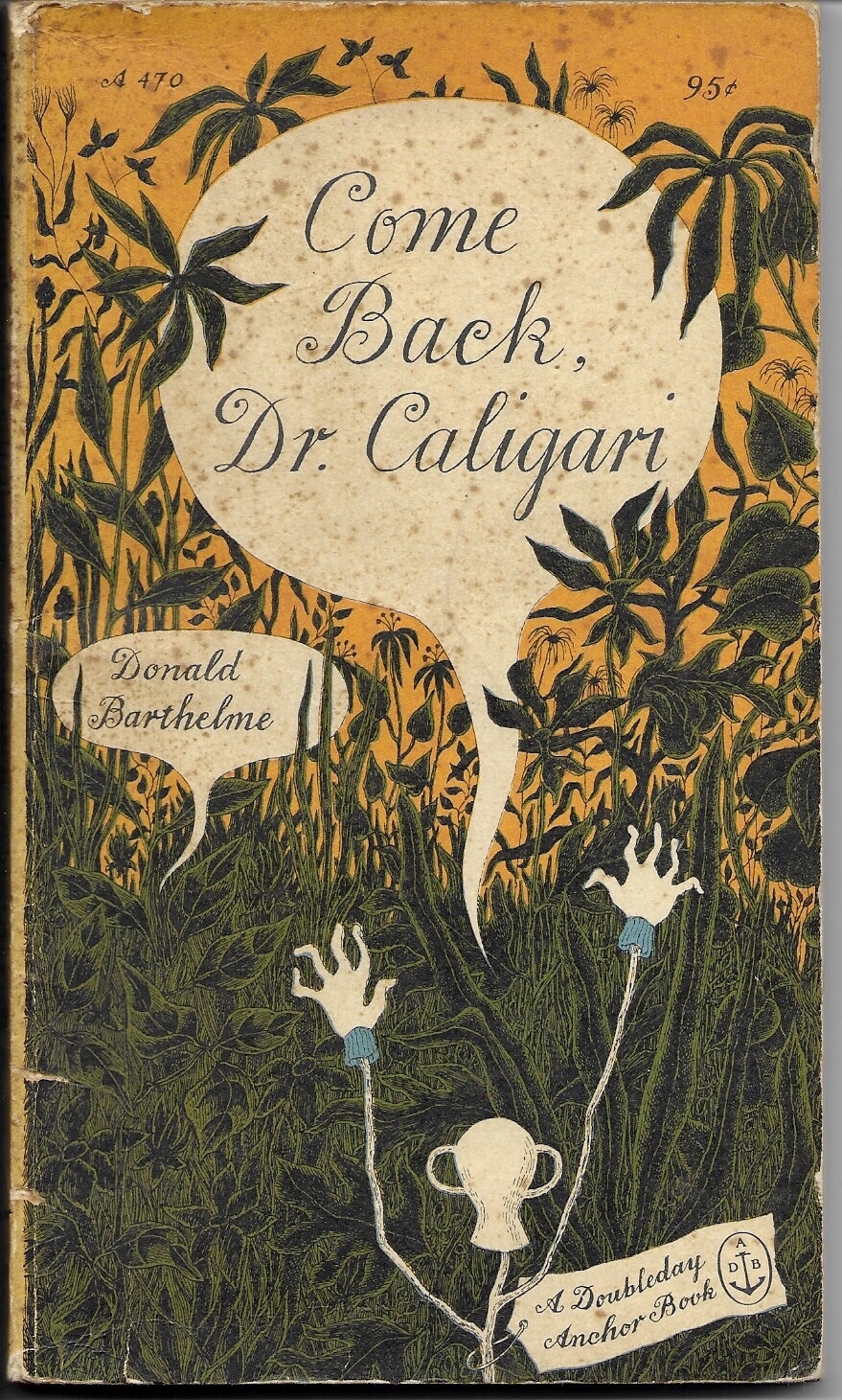

I have been slowly making my way through the stories in Anna Kavan’s collection Machines in the Head, which is available (today!) now from NYRB. I have a full review coming next week, but it’s Good Weird Stuff. If you pick it up, I recommend skipping to the later stories and working backwards—Kavan eventually absorbs the Kafka-anxieties that permeate the earlier texts and synthesizes it into something all her own. The book is not illustrated by the author.

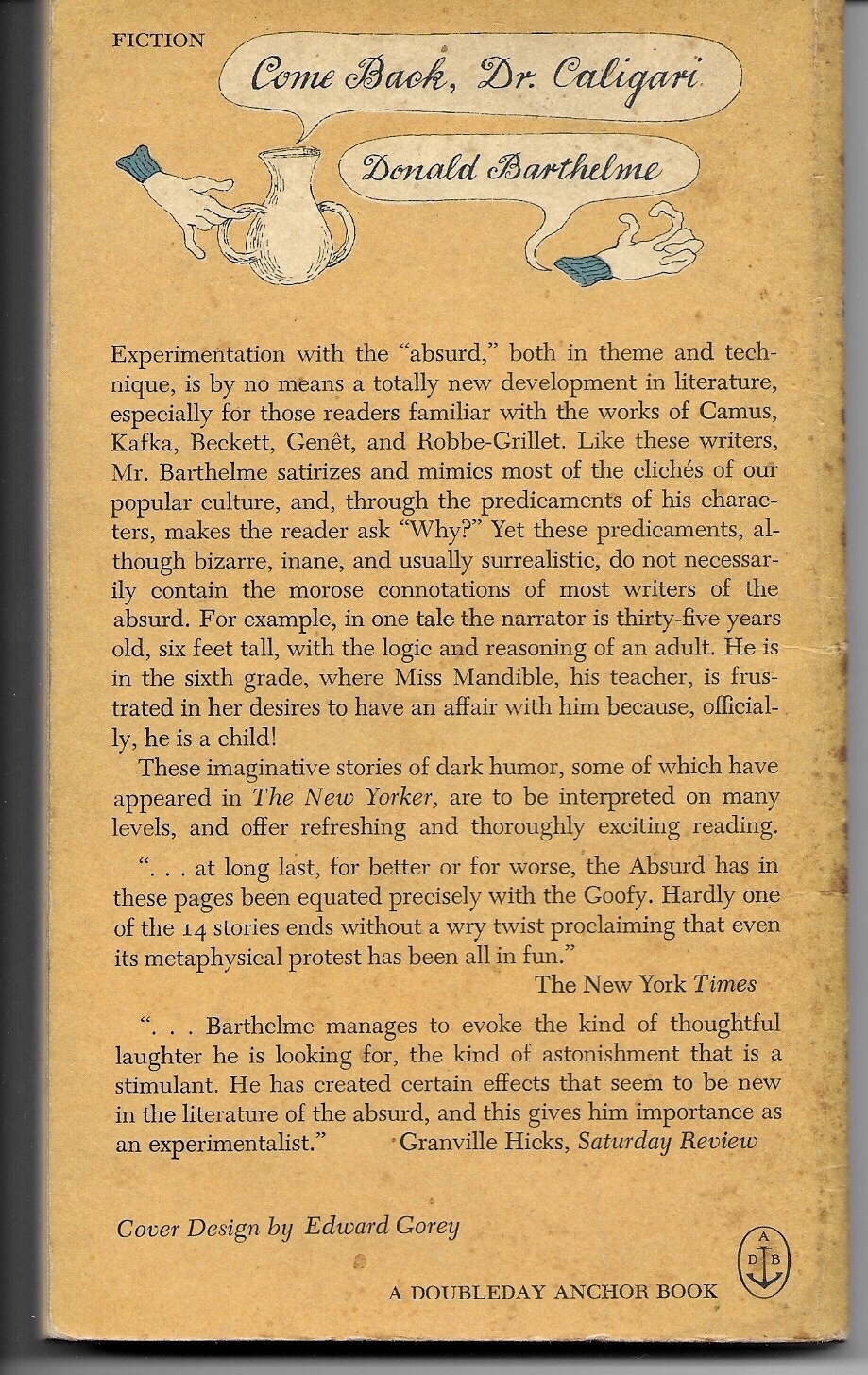

The Great American Novelist Charles Portis died yesterday. I pulled his books out, took a pic, wrote a post. Of his five novels, I’ve yet to read Gringos. I ended up reading the first 60-odd pages of it last night, after having pulled it down, and the sentences are too good to not keep going. Portis’s command of voice is amazing, and I love that he’s returned to the first-person here—in this case, the voice of Jimmy Burns, an American living in Merida, working as a part-time tomb raider, but mostly just helping out gringos and Mexicans alike. Gringos is both comic and ominous, cynical and joyful so far. I will keep going. The book isn’t illustrated, but here’s a taste of the prose, from a page I doggeared last night:

And so little fellowship among the writers. They shared a beleaguered faith and they stole freely from one another—the recycling of material was such that their books were all pretty much the same one now—but in private they seldom had a good word for their colleagues.

The notation is about alien-Mayan-conspiracy books, but I think it works as a take on literature in general.

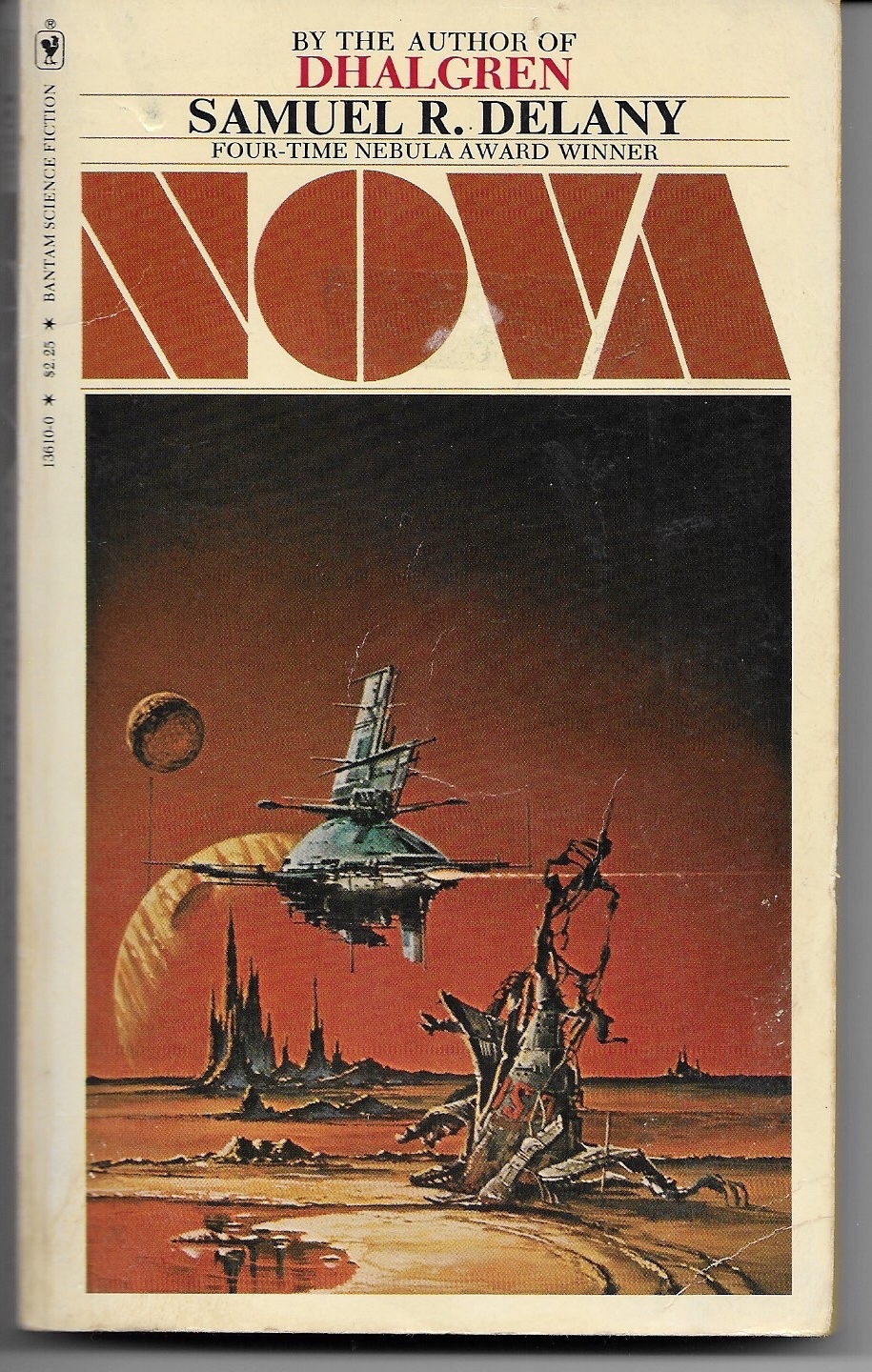

The spine down there at the bottom with its own glyphs is Anasazi, a graphic novel by Mike McCubbins and Matt Bryan. It’s really, really good—I’ve read it twice now, and I have a review planned for The Comics Journal next month. I wrote about it a bit here, saying;

The joy of Anasazi is sinking into its rich, alien world, sussing out meaning from image, color, and glyphs. The novel has its own grammar. Bryan and McCubbins conjure a world reminiscent of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian novels, Charles Burns’ Last Look trilogy, Kipling’s Mowgli stories, as well as the fantasies of Jean Giraud.

This book is, of course, illustrated by the authors:

Blog about some recent reading

Blog about some recent reading

Blog about some recent reading

Blog about some recent reading