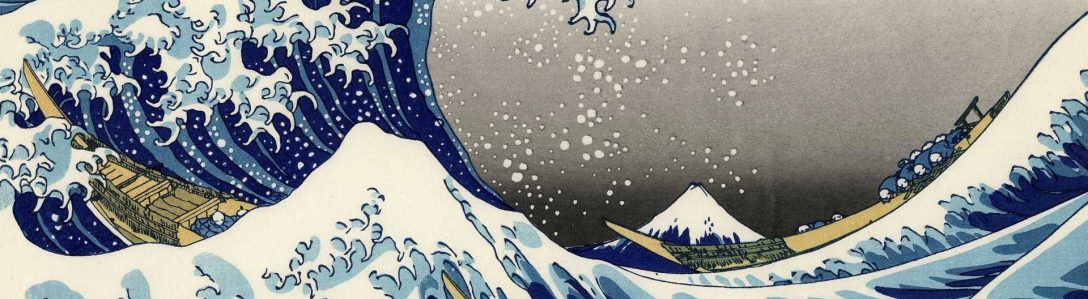

Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake. Mass-market paperback from Ballantine Books, 1968. Cover art by Bob Pepper (not credited); no designer credited.

The first of Mervyn Peake’s strange castle (and then not-castle trilogy (not really a trilogy, really)), Titus Groan is weird wonderful grotesque fun. Inspirited by the Machiavellian antagonist Steerpike, Titus Groan can be read as a critique of the empty rituals that underwrite modern life. It can also be read for pleasure alone.

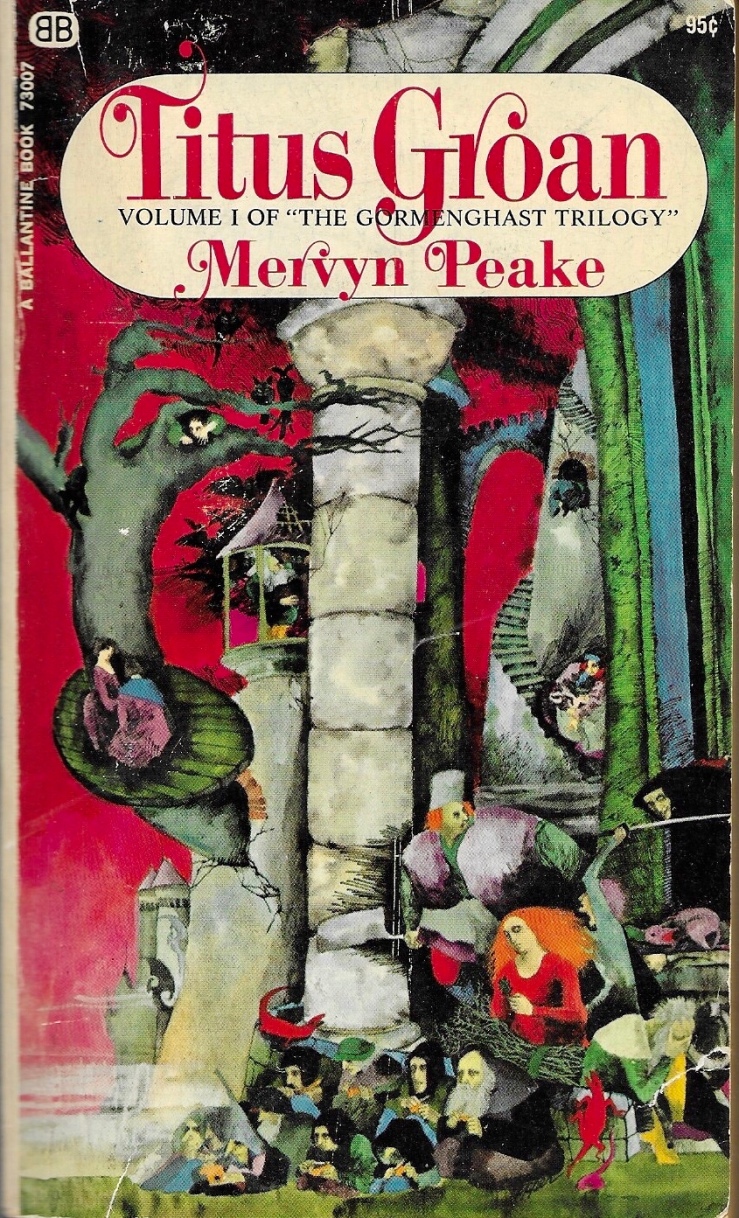

Gormenghast by Mervyn Peake. Mass-market paperback from Ballantine Books, 1968. Cover art by Bob Pepper (not credited); no designer credited.

Probably the best novel in the trilogy, Gormenghast is notable for its psychological realism, surreal claustrophobia, and bursts of fantastical imagery. We finally get to know Titus, who is a mute infant in the first novel, and track his insolent war against tradition and Steerpike. The novel’s apocalyptic diluvian climax is amazing.

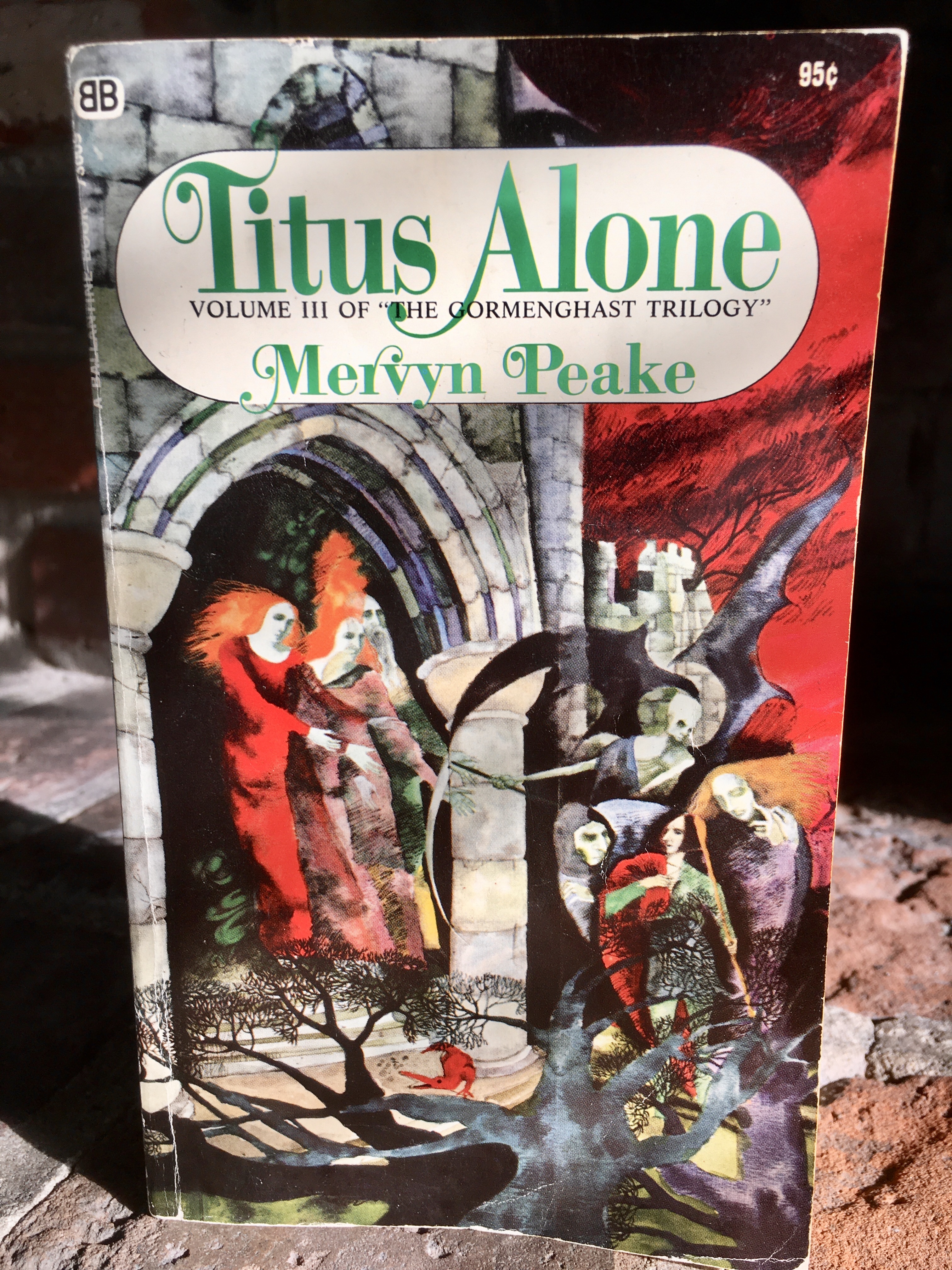

Titus Alone by Mervyn Peake. Mass-market paperback from Ballantine Books, 1968. Cover art by Bob Pepper (not credited); no designer credited.

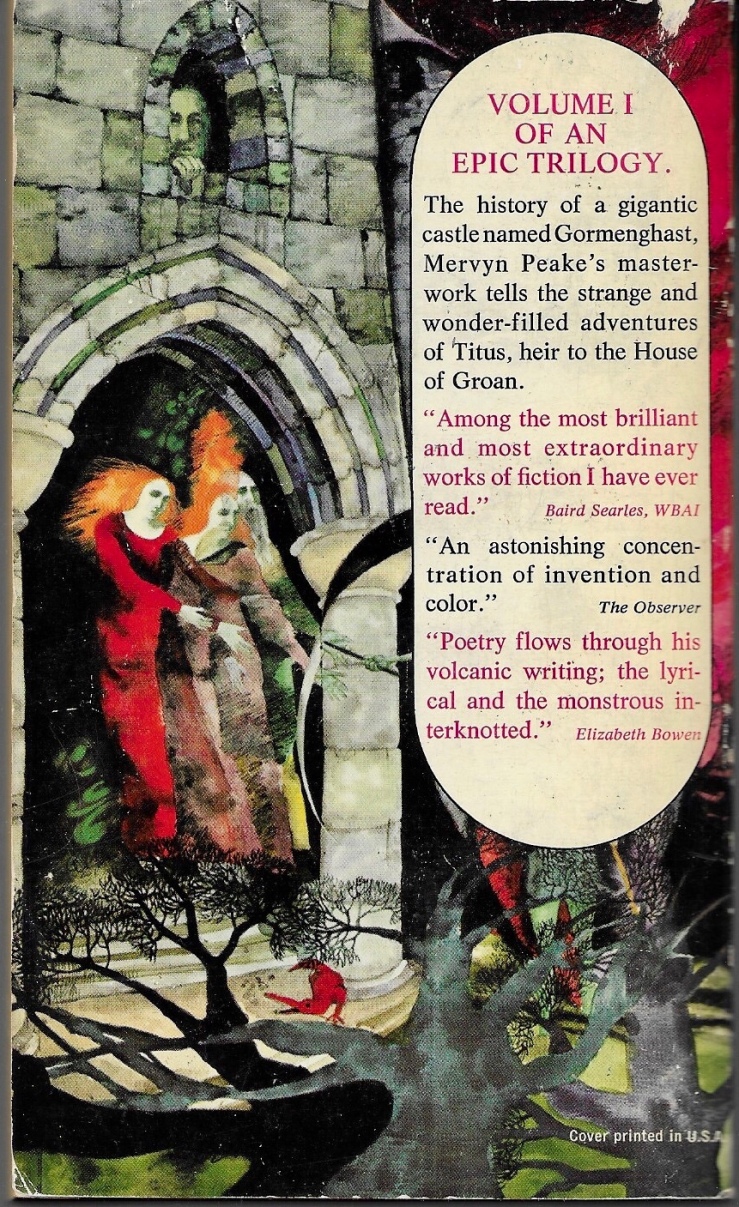

I don’t usually include back covers in these Three Books posts, but I just love the way that Bob Pepper’s back-covers segue into each other.

Is Titus Alone my favorite in the trilogy, or is it just the one I read last? I don’t know. It’s a kind of beautiful mess, an episodic, picaresque adventure the breaks all the apparent rules of the first two books. The rulebreaking is fitting though, given that Our Boy Titus (alone!) navigates the world outside of Gormenghast—a world that doesn’t seem to even understand that a Gormenghast exists (!)—Titus Alone is a scattershot epic. Shot-through with a heavy streak of Dickens, Titus Alone never slows down enough for readers to get their bearings. Or to get bored. There’s a melancholy undercurrent to the novel. Does Titus want to get back to his normal—to tradition and the meaningless lore and order that underwrote his castle existence? Or does he want to break quarantine?

Titus Escapes might have been a better title for Peake’s third book, and its spirit of escape and adventure seem more compelling and comforting to me now than they did a month ago when I read this book.