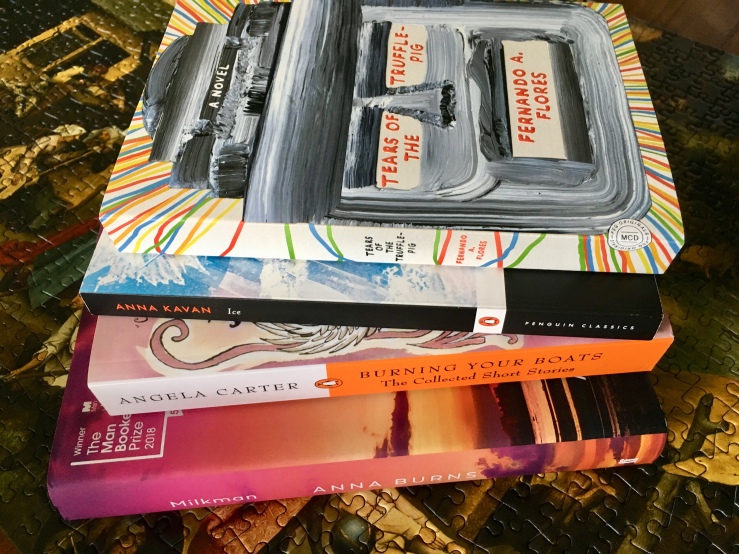

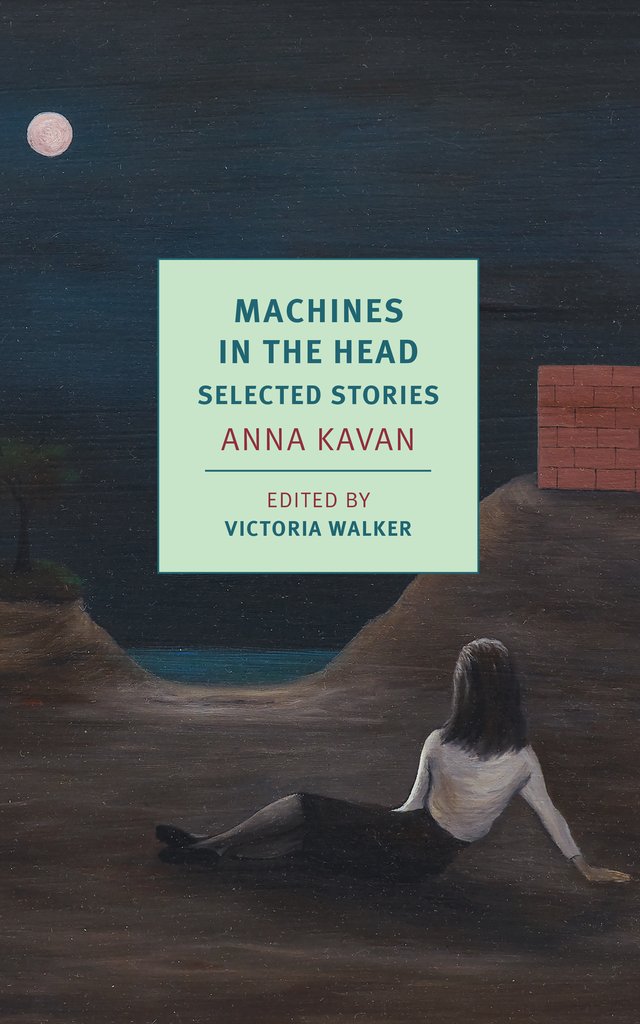

Machines in the Head, new from NYRB, compiles twenty-three Anna Kavan stories that were originally published between 1940 and 1975, as well as one previously unpublished story. The stories here, culled from five previous collections, show not so much a stylistic evolution over three decades of Kavan’s writing as they do a writer pushing herself into ever stranger territory. And while Kavan’s experimental forms shift from story to story, her modes of radical ambiguity, rattling paranoia, and sinister menace course through the collection, giving it a strange coherence.

Machines in the Head is arranged chronologically, with the first nine stories coming from Asylum Piece (1940). These stories announce themes and images that repeat throughout Kavan’s writing and this new NYRB collection: sleep, dreams, ice, sun (and the lack of sun), prisons, asylums, hospitals, lovers, friends (and the absence of friends), enemies, persecutors, mysterious patrons, strange summonses from abstract authorities, sentencing and judgment, windows, walls, doors.

“Going Up in the World” is a miniature study of cold anxiety in which the unnamed protagonist suffers alienation from the “Patrons” who seem to abandon her. “The Enemy” is five paragraphs of Kafkaesque persecution and paranoia. In “The Summons,” an ugly waiter ruins a meal with an old friend, and our narrator is soon taken away by an ambiguous authority, only to return to dinner to have her friend urge her to go back to the authority on her own volition. The nightmare-dream logic here is part and parcel of Kavan’s style, as is the the conclusion of “The Summons”:

…I began to wonder, as I have wondered ever since, whether the good opinion of anybody in the whole world is worth all that I have had to suffer and must still go on suffering — for how long; oh, for how long?

Pretty much every tale in Machines in the Head ends in existential suffering, inconclusive menace, our outright doom. The narrator of “The Summons” tells us at one point that “a feeling of dread slowly distilled itself in my veins,” a line that could fit neatly into any of the stories here.

Suffering and despair continue in “At Night,” where the narrator’s bedroom is a “jailer,” her bed her “coffin.” The story’s surrealist touches capture the all-too-real horror of insomnia. “Machines in the Head” continues the sleep motif, showing us the terror of that tyrant, the alarm clock. Kavan conveys the awful moment many of us experience upon awakening too early:

Roused in this brutal fashion, I jump up just in time to catch a glimpse of the vanishing hem of sleep as, like a dark scarf maliciously snatched away, it glides over the foot of the bed and disappears in a flash under the closed door.

“Asylum Piece II,” however, suggests that there is trouble in dream:

I had a friend, a lover. Or did I dream it? So many dreams are crowding upon me now that I can scarcely tell true from false: dreams like light imprisoned in bright mineral caves; hot, heavy dreams; ice-age dreams; dreams like machines in the head.

In “The End in Sight,” our narrator, having “received the official notification of my sentences,” experiences time’s passing “like shadows, like dreams,” again suggesting that dreams and sleep are not the solution to anxiety and unease. “The End in Sight” concludes with our narrator still in the grips of anxiety, waiting to be carted away by invisible and unnamed forces.

Asylum Piece was the first collection that Kavan published under the name “Anna Kavan.” She previously had written under her legal name, Helen Ferguson, but took “Anna Kavan” (from a character in her 1930 novel Let Me Alone) first as a pen name and then later as her new personal identity. It’s hard not to read Kavan’s fiction as largely semi-autobiographical, while also recognizing that much of that biography was the result of imaginative invention and re-invention. Asylums and psych wards show up in her stories so much because she spent quite a lot of time in such places. Kavan suffered depression and attempted suicide several times in her life. Alienation and loneliness permeate her work: her characters can never seem to truly know each other, to truly communicate. Kavan was essentially alienated from her parents; her father abandoned the family (and later committed suicide), and she spent most of her youth at boarding schools. Both of her marriages failed before the publication of Asylum Piece, a fact that underscores her stories’ curves toward despair. She did have romantic relationships later, doomed as they were, and also was extremely close to Dr. Karl Bluth, the German psychiatrist who prescribed her heroin from the time that he met her until he died in 1964.

Iterations of Bluth—sympathetic doctors—-start to appear in some of Kavan’s stories stories starting with I Am Lazarus (1945). The stories here are longer, richer, and more focused than those in Asylum Piece (but still strange, strange, strange). The nightmare of the Blitz hangs over the tales, which are populated with doctors, nurses, and soldiers.

“Palace of Sleep” — the first third-person piece in the anthology is set in a mental hospital. “Palace” picks up the night shift motif of Asylum Piece, focusing on an unnamed patient undergoing treatment for narcosis. “The Blackout” continues the narcoleptic motif. In this story—one of the strongest in the collection—a soldier who had blacked out for five days talks to psychologist. The soldier parcels out bits of a tragic life story, redeemed in part by the aunt who eventually raises him after he’s orphaned. There’s an oedipal undercurrent to “The Blackout,” which circles around a profound horror without actually naming the crime at the heart of the tale. “Face of My People” is another psych ward piece, with a tone and development worthy of J.G. Ballard. (Ballard was a big fan of Kavan’s fiction.)

“The Gannets” is another very strong piece. In five visceral paragraphs, Kavan condenses the horror of World War II into a strange allegory of terrible violence. “The Gannets” contains one of the strongest images in the whole collection. It’s shocking, really, when it happens—so much of her writing runs on unspecified dread and slow-motion menace, that when she does deploy concrete horror, the effect is devastating. I won’t spoil that devastation by quoting the image, but I will share the story’s final paragraph:

How did all this atrocious cruelty ever get into the world, that’s what I often wonder. No one created it, no one invoked it, and no saint, no genius, no dictator, no millionaire, no, not God’s son himself, is able to drive it out.

“Our City” is a longish Kafkaesque exercise that feels similar to the early short stories “Airing a Grievance” and “The Summons,” but with more absurd humor and more control. Kavan elides details that would allow us to identify the titular city as London during the Blitz. Instead of realism, we get something closer to a psychological portrait of a place under the most extreme duress. “Our City” is a slow-motion panic attack, a fever dream that sprawls outward but refuses to resolve.

Machines in the Head includes just three stories from A Bright Green Field (1957), but all are excellent. “A Bright Green Field” is the surreal story of a visitor (to where?!) who witnesses “prone half-naked human bodies, spreadeagled on the glistening bright green wall of grass.” The bodies are bound “by an arrangement of ropes and pulleys [with] semi-circular implements of some sort fastened to their hands.” The bizarre image has an even more bizarre explanation: These people are employed in the Sisyphean task of mowing the grass in this fashion. Why? Well, look, are you expecting a rational answer?–

That poison-green had to be fought; cut back, cut down; daily, hourly, at any cost. There was no other defence against the mad proliferation of grass blades, no other alternative to grass, blood-bloated, grown viciously strong, poisonous and vindictive, a virulent plague that would smother everything, everywhere, until grass and only grass covered the face of the globe

If “A Bright Green Field” is allegorical—and it really, really doesn’t have to be—perhaps it’s an ironic allegory of humanity’s perverse relationship to ecology.

The plot of “Ice Storm” is scant: a woman travels from New York City to Connecticut to visit some friends and decide whether or not to leave America. It turns out that she doesn’t really like her friends that much, and she’s ultimately unable to make a decision, “Because there were far too many decisions to make about everything and no permanent set of values by which to decide.” With its touches of realism, “Ice Storm” feels anchored in autobiography. (The title and much of the imagery suggest that “Ice Storm” might be the germ–or a germ—of Kavan’s 1967 novel Ice.) Kavan interposes newspaper headlines, seemingly at random, throughout the story, a device that might have come off as a gimmick; instead the headlines serve to highlight the narrator’s alienation from reality.

“All Saints” is the most avant-garde exercise in the collection. The story—story is probably not the right word—the story seems to drift between two or three consciousnesses that riff on decadent decline and imminent death. I’ve read it several times and still can’t puzzle it out, which is why I like it so much, I suppose. (I put a big star on the margin next to the line, “the end of every project comes down to the rat.”)

The stories from Julia and the Bazooka (published in 1970, two years after Kavan’s death) are the first to deal openly and frankly with drug addiction. “The Old Address” is a sad first-person number steeped in agoraphobia. Our addict-narrator, discharged from the clinic, ventures into an anonymous but teeming world which she murders in her imagination in an abject and revolting sequence:

Huge black clots, gouts, of whale blood shoot high in the air, then splash down in the mounting flood, soaking the nearest pedestrians. Everybody is slipping and slithering, wading in blood. It’s over their ankles. Now it’s up to their knees. All along the street, children start screaming, licking blood off their chins, tasting it on their tongues just before they drown.

The poison-blood-drowning-murder vision continues for several more paragraphs, before the narrator capitulates to her own panic, realizes that there’s “only one way of escape that I’ve ever discovered,” hops in a taxi, and tells “the man to drive to the old address.” Another sad ending.

The magical realism of “A Visit” initially suggests the possibility of happy ending. Kavan gives us a rare tropical locale, where our narrator receives an erotic night visitant, gorgeous a leopard. She longs to meet the leopard again, but never sees him until he returns in a new form:

One day while I was on the shore, I saw, out to sea, a young man coming towards the land, standing upright on the crest of a a huge breaker, his red cloak blowing out in the wind, and a string of pelicans solemnly flapping in line behind him.

She glimpses the youth and leopard together just one more time, and lives the rest of her life in disappointed waiting. Sometimes the pair enter her dreams though, which only weighs her down with “the obscure bitterness of a loss” — which she blames on herself. Kavan doles out a magical epiphany, only to hobble it down to a kernel of disappointment, another machine in the head.

“Fog” tells the story of a woman high on heroin, driving her car at a dangerous speed through foggy streets. She tells us how peaceful she feels, then adds: “The feeling was injected, of course. She ends up committing a terrible crime on her joyride, and is soon brought in by the police. As the fog of the heroin wears off, the story skirts a bipolar line reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” In the end, the narrator wishes to nullify her consciousness—to “stay deeply asleep and be no more than a hole in space.”

The hero of “Julia and the Bazooka” is unstuck in time. Kavan essentially tells a version of her own life story here, with its sad childhood, failed marriages, and heroin addiction. (The titular “bazooka” is a syringe.) In some paragraphs, Julia is a young child; in others, she is a new bride, or a young woman traveling the world, or meeting the doctor who advises her to stick with heroin — “Without it she could not lead a normal existence, her life would be a shambles, but with its support she is conscientious and energetic, intelligent, friendly.” In other paragraphs, Julia is dead. Indeed, like Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall,” “Julia and the Bazooka” shows us a consciousness unraveling towards death.

The final two stories in Machine in the Head, while as strange and disconcerting as anything in the collection, are notable for one major difference: both have happy endings. “Five More Days to Countdown” (the only story here from 1975’s posthumous My Soul in China) is a gleeful picaresque exploding in energy. The story centers around an experimental school run by a genius named Esmerelda and her hapless husband. Pretty soon the school is in the grips of a youth rebellion that turns into outright violent revolution—and all five days before Christmas:

A sack of mail, directed to Santa, was delivered later. Sifting through through the contents, through the requests for definitive trendy kaftans, avant-garde night caps, exciting fab fun-fur hoods, switched-on gear of all kinds, I found the more basic items. Junior practical fighting techniques. Guerrilla warfare for the under-sixteens, including training in hand-to-hand combat. Do-it-yourself weapons for schools: simple construction of mortars, flamethrowers, ballistic missiles. How to construct an ambush, a booby trap. Useful tips on terrorism, napalm, nuclear devices, with sections on robbery with violence, blackmail, piracy on the high seas, arson, karate.

The gleeful satire here makes me wish there were more Kavan pieces like this. While the energy of the story matches the picaresque energy of Ice, there’s nothing close to the humor of “Five Days to Countdown” in the rest of the collection. (I’m also a sucker for surreal British boarding school revolution stories, like Lindsay Anderson’s 1968 film if….) The absurd vivacity of the tale culminates in a surreal apotheosis of sorts:

Esmerelda and I are swinging high over the world, conveyed through a sky full of snow by eight polar bears, whose bells jingle. Gosh, I never expected a happy ending.

Gosh, neither did I.

The previously-unpublished “Starting a Career” also ends on a positive, if ironic, note. The narrator (yet again!) receives a summons. This time, Kavan names the summoner—it’s Lord Legion, a-not-quite-ousted relic of older times who contests the President (the narrator’s employer) for power. The narrator agrees to become a spy for Lord Legion, a thrilling idea that loads his imagination with all kinds of fantasies.

I was about to become the world’s best-kept secret; one that would never be told. What a thrilling enigma for posterity I should be!

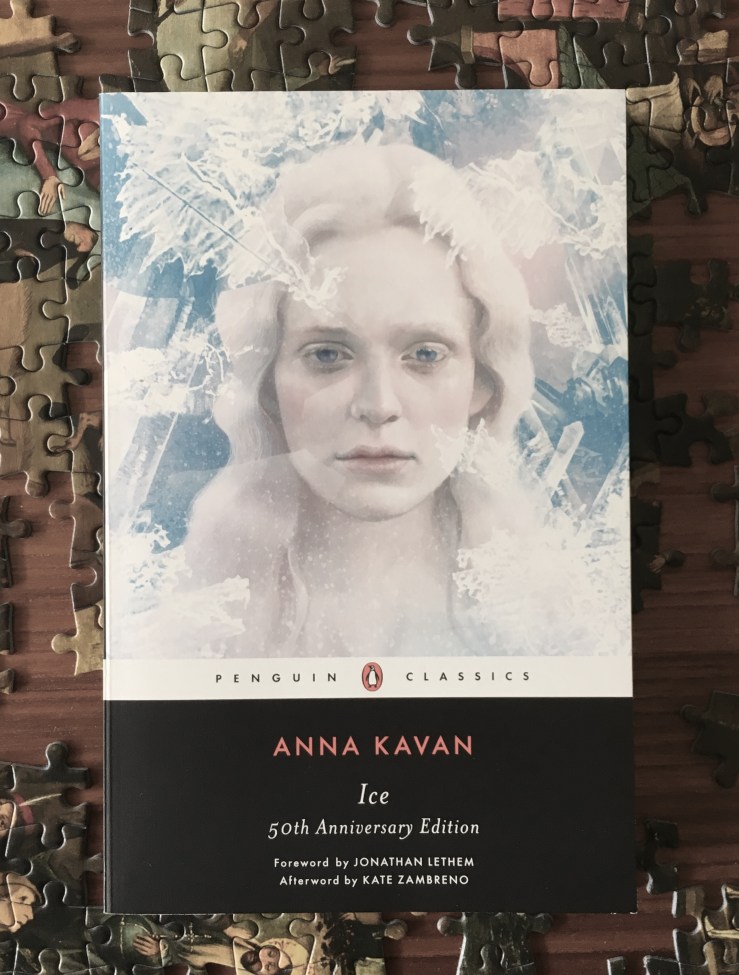

The lines ironically point to Kavan’s own sense of her legacy. While she maintained some success in her lifetime as a writer, she knew that the experimental and avant-garde nature of her writing would guarantee that, well, if she wasn’t exactly “the worlds best-kept secret,” she was definitely bound to some measure of obscurity. The world has a way of catching up to the avant-garde though, and the recent Penguin reissue of Ice and this new NYRB collection suggest that Kavan has found a broader, if not exactly mainstream, audience. Her writing is still challenging today—which is what makes it so engaging. As the collection’s editor Victoria Walker puts it in her foreword—

Kavan’s writing is not to everyone’s taste. Reading her work can be disorienting and discomforting; her narratives shift disconcertingly between past and present tense, first and third person. Her characters are often disagreeable, misanthropic, self-absorbed, priggish or delusional, and the paranoia of her nameless narrators is infectious.

Walker acknowledges that it’s not possible to neatly situate Kavan into any one group of writers. She points out that Kavan is definitely from the Tree of Kafka, and also admired Joyce and Woolf. Walker does make a small canon of writers on Kavan’s wavelength though, and I think the group is is worth listing out: H.P. Lovecraft, Jean Rhys, Jane Bowles, Leonora Carrington, Unica Zurn, Ann Quin, and J.G. Ballard. (I’d also throw in João Gilberto Noll, Gisèle Prassinos, Edgar Allan Poe, and even Roberto Bolaño.)

Walker’s editing of the anthology is commendable. Images echo earlier images, motifs build, themes swell, and Machines in the Head offers what I believe to be a close-to-comprehensive showcase of Kavan’s proclivities and range. At the same time, I would’ve loved just a few more stories from the mid to later volumes, A Bright Green Field, Julia and the Bazooka, and My Soul in China. It’s probable of course that Walker selected the more achieved pieces from those volumes, dispensing with sketches and experiments that didn’t quite come off—but I’d love to read, say “Lonely Unholy Shore” or “Mouse Shoes” from A Bright Green Field, or “Experimental” and “Obsessional” from Julia and the Bazooka, and really, just any other story from My Soul in China.

I would advise readers interested in Machines in the Head to start with the mid-late stuff. Maybe get into anything from A Bright Green Field and move forward a bit, before snacking on some of the shorter tales from Asylum Piece. You’ll get the full picture and also, perhaps, a more satisfying read. The selections from Asylum Piece are good but so chilly that they invoke a bit of brain freeze.

Machines in the Head provides a fantastic and surreal overview of an overlooked cult favorite, a writer whose work—long championed by those marvelous archivists, the sci-fi nerds—deserves a broader audience. The stories here will not comfort you and they won’t affirm any heroic sympathy for whatever-the-fuck the human condition is supposed to be. But they are terrifyingly, menacingly real in all their sinister surrealism. Recommended.

Blog about some recent reading

Blog about some recent reading