I have acquired a goodly amount of books in the last two weeks and failed to do any of these silly “books acquired” posts about them, having been busy with summer classes and occupying summer-bound children (and, admittedly spending too many free hours rewatching Deadwood so that I can watch the Deadwood film and doing a Brueghel puzzle, and not really writing).

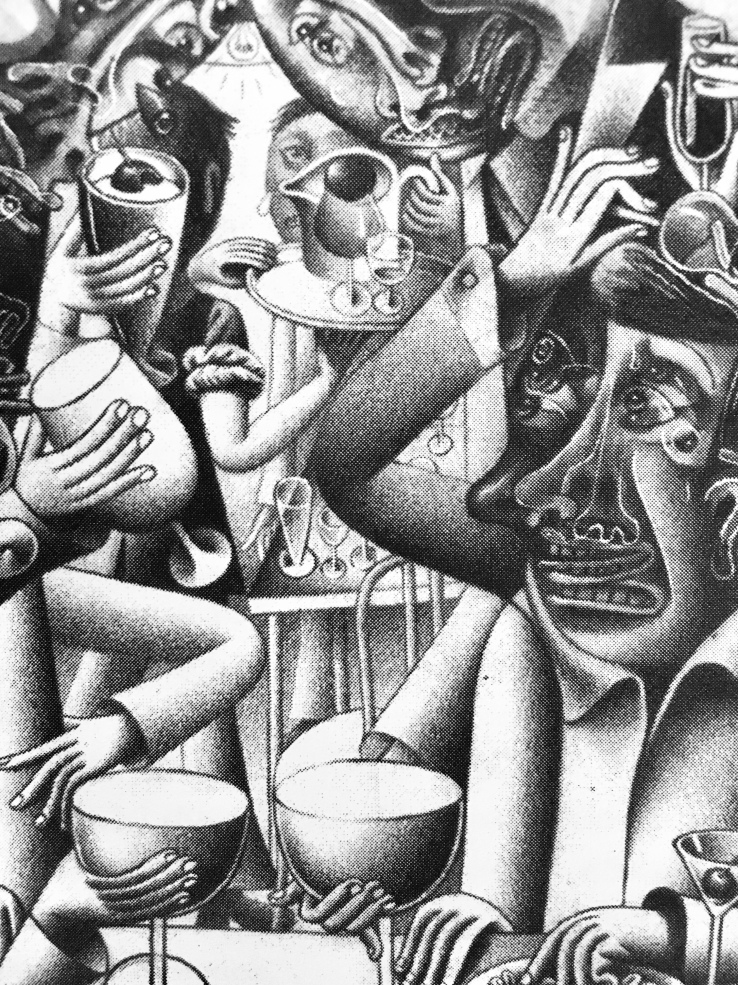

I ordered Pierre Senges’ strange little book Geometry in the Dust. It’s new in English translation by Jacob Siefring from publisher Inside the Castle. (Siefring also translated Senges’ novel The Major Refutation, which I read a few years ago.) Geometry in the Dust is a rectangular novella that includes black and white illustrations by Patrice Killoffer. The text is set in two columns, with occasional inset notes set in a smaller font.

I mention the size/shape, the inset notes, and the illustrations because, for whatever reason, these things make the reading experience even odder (although I can’t articulate why, and to be clear, I find the oddness compelling).

Told in the articulate, observant, and often-funny first-person voice of the “sole faithful minister…advisor, chamberlain and…scapegoat” of a certain monarch—a “you” this minister addresses—like, you, the reader—told in this funny and strange voice, Geometry in the Dust is “about” (a term that we’d have to place under suspicion here) the planning, the mental construction of a great city. A sort of extended thought experiment, Senges’ novella captivated me for two quick afternoon reads, and I hope to go through it again in preparation for a proper review. For now, I’ll lazily compare it to Borges, Calvino, Perec, and Antoine Volodine—writers that Senges does not imitate, but seems to drink from the same imaginative well as.

I went to my beloved used bookstore last Friday to browse, as is often my habit, and while I didn’t find any of the Joy Williams Vintage Contemporaries I was hoping to find, I did find a copy of Anna Kavan’s 1967 novel Ice. I’ll admit I hadn’t heard of Kavan until I read Ann Quin’s fantastic novel Berg (which I reviewed recently on this blog). I subsequently read/heard Kavan’s name brought up in conversations concerning Quin. Ice is my next read.

I also spied a new copy of Anna Burns’ Milkman at half price and picked it up. I’d heard good things about the novel—that it’s weird, challenging; that a lot of folks hated it. And, like, look—Ann, Anna, Anna. Why not? Milkman after Ice?

I got home to three separate review copies in the mail, a bit of an overwhelming shock, really, as one is NYRB’s new edition of Gregor von Rezzori’s The Death of my Brother Abel (translated by Joachim Neugroschel and revised by Marshall Yarbrough) b/w Cain: The Last Text (translated by David Dollenmayer). (The novel and its sequel have been published as Abel and Cain.) At nearly 900 pages it is a brick, or maybe a nice big hole to fall into soon.

I was also pleasantly surprised to see that Contra Mundum Press has published Iceberg Slim’s novel Night Train to Sugar Hill, which was never published in Slim’s (aka Robert Beck’s) lifetime. I’m not sure if this is the first publication of this late novel, but I think it is.

I had read some of Greg Gerke’s essays at LARB and 3:AM before getting See What I See (which is out later this year), and am generally impressed with what I’ve read so far. I admit that I skipped around almost immediately, reading (or rereading, in one case) pieces on William Gass and William Gaddis, before turning through pieces on Paul Thomas Anderson and Ingmar Bergman. An essay ostensibly on Mike Leigh’s film Mr. Turner is really about criticism itself, and contains this paragraph:

Critics have a job incompatible with their raw materials. They are to respond promptly and pithily to a work of art—the very life of which changes by different viewings, listenings, and readings, and at different times in one’s life. It is like being a bull rider—one being is not made to situate itself onto the other. Yet, our culture still respects some views and honors the guidance offered. In conjunction, it is no exaggeration to say we live in an era that disposes of language, including the etiolation of the sentence, punctuation, spelling, and grammar by the rush to judgment, and by the ego not caring what it’s form of thought is like, only that it’s owner’s name is lit up. Our species is changing—words, because they are not respected, boil more easily over into lies and exaggeration, disregarding the best humanistic advice possible, courtesy of Shakespeare: “Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.” Where once words were imbricated and limned to grasp at wisdom, we now have the sweet satisfactions of irony, the insulting tweet, and the ham-handed “article” on why this or that does or doesn’t meet one’s satisfaction.

Gerke’s essay reminded me that I had wanted to see Mr. Turner (admiring both Leigh and his subject). (And if Gerke is a namegoogler—I loved Boyhood.)