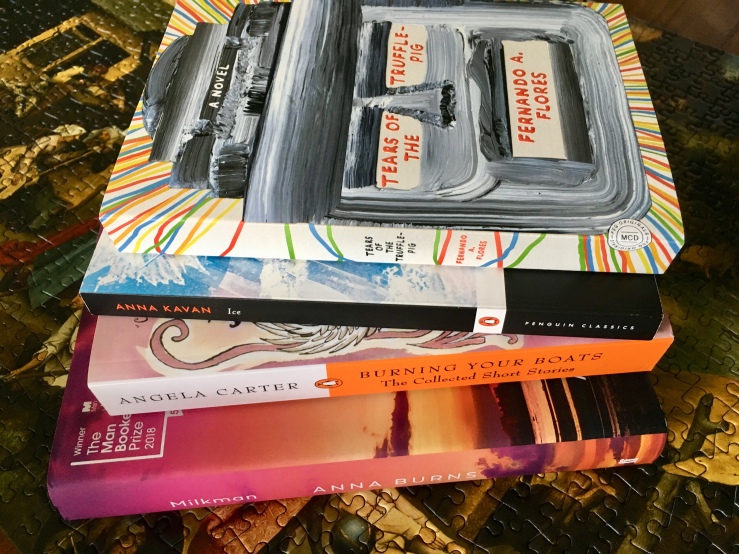

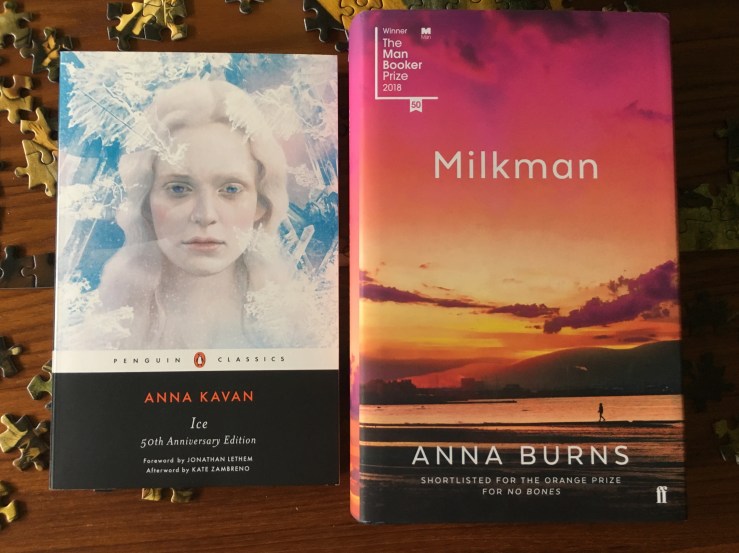

Anna Burns’s third novel Milkman won the 2018 Man Booker Prize and was reviewed in a number of prominent publications. It hardly needs my recommendation at this point, but I do recommend it: It’s artful, horrific, endearing, and troubling, a claustrophobic, unrelenting depiction of terror and paranoia. It’s also really funny.

Scattershot snippets I’d heard about Milkman indicated that the novel was “difficult” and even “confusing” or “challenging,” in large part because of the novel’s major stylistic trope—the first-person narrator refuses to ascribe clear, “stable” names to the characters in the book.

Our narrator, an eighteen-year-old woman in Northern Ireland, is referred to variously as “daughter,” “middle sister,” and “maybe-girlfriend” (among other titles) depending on whom she is interacting with. Similarly, most other characters are referred to in such terms: “oldest friend,” “third brother-in-law,” or simply “neighbour,” a nebulous catchall. (There are “named’ characters of a sort though: “chef,” “tablets girl,” “nuclear boy,” “real milkman,” and, of course, the horrific titular character “milkman.”) This narrative device might disarm some readers initially, but I found it easy to sink into our first-person narrator’s distinctive, brave, funny voice, a voice that emerges into new states of knowing and new states of consciousness as the novel unfolds.

Naming, or rather not naming is especially rhetorically significant given the setting and context of Milkman. It is the late 1970s, and the strange hot cold silent loud civil war in Northern Ireland has been going on for the entirety of our narrator’s lifetime. It has fully colonized her consciousness, shaped her language. Significantly, the conflict itself cannot be named except obliquely, nebulously. When our narrator tries to describe this zeitgeist, she employs the vague term “political problems”; her third brother-in-law replies, “Are you referring to the sorrows, the losses, the troubles, the sadnesses?”

Similarly, phrases like Protestant or Catholic are never employed, let alone anything as specific as the British army and the IRA, or unionists and nationalists. There’s just “their side” and “our side.” The sides don’t ultimately matter in Milkman. Rather this is a novel about what a constant state of their side-our side does to a person.

Our narrator, bound since birth in this state of their side-our side, has difficulty clearly communicating the central conflict of Milkman. She finds herself the strange victim of the milkman, an older married man who is a top level operative of the renouncers, anti-government paramilitaries who essentially run her district. (To be clear, he is not a real milkman. There is a real milkman though, and he’s a good guy.) Milkman stalks the narrator, creeping up next to her in his white van as she walks home reading 19th-century novels (a habit that marks her as “beyond the pale,” an outsider in her community) or waylaying her as she runs in the park. He’s a nightmare force of patriarchal ideology, a creeper at the edge, but utterly empowered.

Milkman isn’t the narrator’s only stalker. No, there’s also Somebody McSomebody, who we meet, sort of, in the novel’s astonishing opening sentence: “The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died.” Somebody McSomebody is a poseur though. He’s a pretend renouncer, a would-be hardman also inscribed in the violent ideology of the the Troubles. The narrator calls him her “amateur stalker.”

The narrator uses variations of the word “stalk” in Milkman, but this word is meant to convey meaning to us, to a readership that might now better understand the term. (This effect of an older voice imposing its wisdom on a younger perceiver persists in Milkman.) What’s clear though is that nobody, or at least nobody in authority, can help the narrator from her stalkers:

That was the way it worked. Hard to define, this stalking, this predation, because it was piecemeal. A bit here, a bit there, maybe, maybe not, perhaps, don’t know. It was constant hints, symbolisms, representations, metaphors. He could have meant what I thought he’d meant, but equally, he might not have meant anything.

Our narrator lives in a constant state of maybe, a trope underscored by her relationship with “maybe-boyfriend” (himself something of an oddball). Maybe-boyfriend is a compelling character in Milkman, and perhaps something of tragic-absurd one as well. (One of the strangest details in the novel: maybe-boyfriend and his brothers are abandoned by his parents so that they can become world champion ballroom dancers—which they do (become world champion ballroom dancers, that is.)) In a particularly strong section of the book, maybe-boyfriend, a mechanic and car enthusiast, brings home the supercharger of a Bentley and shows it off to his neighbors. The jovial atmosphere slowly slides into a tense then paranoid exchange—Bentleys are English after all—which eventually erupts into violence. It’s a remarkably controlled episode that describes the ideology of the Troubles in a way that a historical textbook never could.

Even though our narrator lives in a perpetual maybe, she still understands her community and can describe it for us. She is intelligent and perceptive, and much of the humor in Milkman evinces from moments where she gets on a rhetorical roll, as when she describes her home as “our intricately coiled, overly secretive, hyper-gossipy, puritanical yet indecent, totalitarian district.” Horror and comedy conjoin in her absurd description of a run-in with the milkman as “talking to a sinister man while holding the head of a cat that had been bombed to death by Nazis.”

Radical horror, violence, and uncertainty percolate in Milkman. Paranoia rules on all levels, but by focusing primarily on the narrator’s being stalked by milkman, Burns offers a concrete portrait of a malevolent force that might otherwise be too sinister and abstract to properly convey in a fictional novel. At the same time, our narrator is able to extrapolate beyond her concrete circumstances to other injustices—

those big ones, the famous ones, the international ones – witch-burnings, footbindings, suttee, honour killings, female circumcision, rape, child marriages, retributions by stoning, female infanticide, gynaecological practices, maternal mortality, domestic servitude, treatment as chattels, as breeding stock, as possessions, girls going missing, girls being sold and all those other worldwide cultural, tribal and religious socialisations and scandalisations, also the warnings given against things throughout patriarchal history that were seen as uncommon for a woman to do or think or say.

Milkman is full of moments like this, rhetorical flights that help weave a richer picture of our narrator’s psychic state.

Milkman also shows us how that psychic state deteriorates. Our narrator was always an outsider, reading novels while walking or going on long runs as a way to tune out reality. Our narrator is aware of this tuning-out; indeed, it is her primary practice. However, as gossip and lies spread about her and the milkman, her consciousness begins to crumble–

Thing was though, before I’d gained the understanding of what was happening, my seemingly flattened approach to life became less a pretence and more and more real as time went on. At first an emotional numbness set in. Then my head, which initially had reassured with, ‘Excellent. Well done. Successfully am I fooling them in that they do not know who I am or what I’m thinking or what I’m feeling,’ now began itself to doubt I was even there. ‘Just a minute,’ it said. ‘Where is our reaction? We were having a privately expressed reaction but now we’re not having it. Where is it?’ Thus my feelings stopped expressing. Then they stopped existing. And now this numbance from nowhere had come so far on in its development that along with others in the area finding me inaccessible, I, too, came to find me inaccessible. My inner world, it seemed, had gone away.

This is a sad, remarkable, and genuinely horrifying passage. We get the horror of un-becoming, a kind of un-becoming that we might find in many other horror-tinged feminist works, from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale to Anna Kavan’s Ice to Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time.

Not only is our heroine emotionally and psychologically drained, she also finds herself physically exhausted by the duress of being stalked—stalked now not only by the milkman, but also by the whispering community. No longer able to take the walks and runs that replenished her, she languishes. The horror and absurdity culminates when she is poisoned, for no real reason, by tablets girl, “our district poisoner” and must recover without the aid of professional medical care. (Nobody in the district can go to the hospital without fear of being thought an informant.)

After a serious bout of purging, the narrator recovers. While recovering, her triumvirate of “wee sisters” asks her to read them a story. Tellingly, they purloin their ma’s copy of The Exorcist. Milkman is a novel of possession and purging, of being inscribed in a preexisting symbolic order and forging a consciousness strong enough to resist and endure that order.

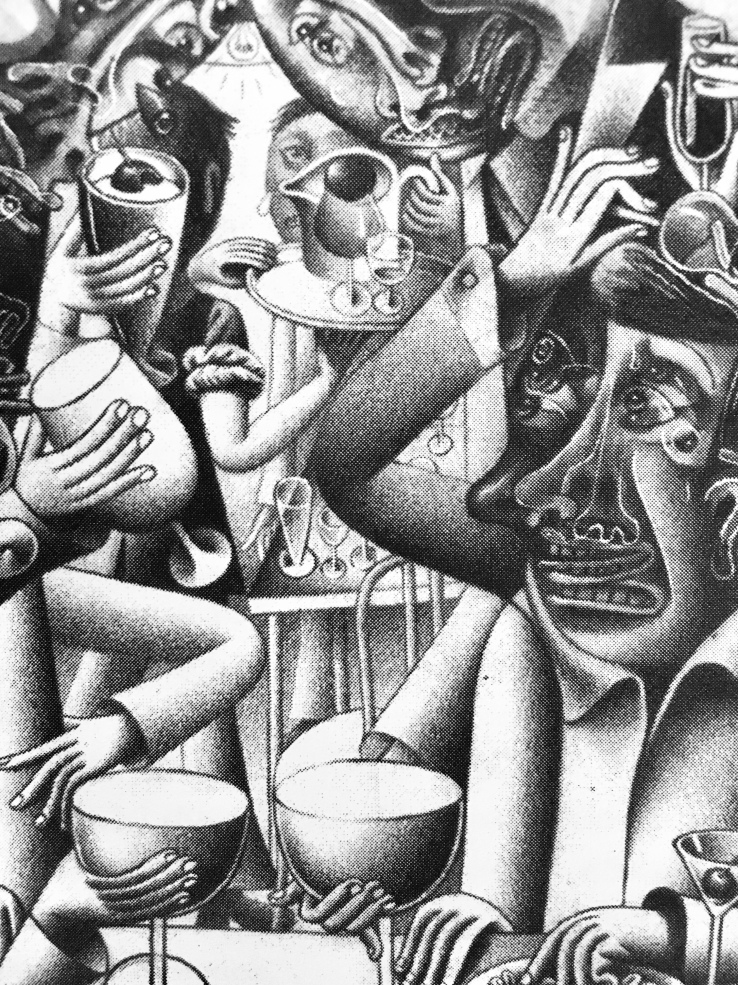

Milkman is a maybe-horror, but also a maybe-comedy (it even ends in a maybe-laugh), and like many strong works that showcase the intense relationship between horror and comedy (Kafka, Brazil, The King of Comedy, “Young Goodman Brown,” Twin Peaks, Goya, Bolaño, Get Out, Candide, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Funny Games, etc.)—like many strong works that showcase the intense relationship between horror and comedy, Milkman exists in a weird maybe-space, a queasy wonderful freaky upsetting maybe-space that, in its finest moments, makes us look at something we thought we might have understood in a wholly new way. Highly recommended.