My spring break, which is to say the spring break of the community college which employs me to teach English, rarely coincides with my children’s spring break, but this year it did, and we took full advantage, spending a week in Atlanta. We stayed in Inman Park, enjoying the BeltLine and the city’s vibe in general. Airport aside, I hadn’t been to Atlanta in twenty years, and I took pleasure in our week there. (I dug the High Museum in particular, and shared some favorites from our visit on Twitter.)

I can’t remember the last time I visited a city and didn’t buy a book. A Capella Books was a short walk from our place; it’s a small, well-curated bookshop with a limited selection. A Capella offered a number of signed books by musicians, including Billy Bragg and Chris Frantz. I thought I might regret not picking up a signed copy of Frantz’s memoir Remain in Love (which I read last year), but I feel no regret as I type this sentence. I also visited Posman Books at Ponce Market. It veers close to something like a tasteful gift shop/stationery joint, but the small fiction and poetry selection is pretty good, even if a lot of it is shelf candy. I think if I’d been willing to drive farther out I might’ve found some deeper cuts. (My wife pointed out that our local used bookstore, 1.1 miles away, has utterly spoiled me.)

Anyway: No books acquired in Atlanta. (I did buy some records though: Fat Mattress’s debut and Fleetwood Mac’s Heroes Are Hard to Find.)

I brought Esther Allen’s new translation of Antonio di Benedetto’s novel The Silentiary with me to reread on the trip. I read it back in January, dogeared it, and started a review, but found that I wanted to let it settle a bit. I liked it the first time round, but the reread revealed a sadder, deeper novel than I had initially estimated.

Other stuff I’ve been reading:

Grace Paley’s late collection of poems, Fidelity. Grand stuff. Sample:

I’ve also been picking through Helen Moore Barthelme’s biography Donald Barthelme: Genesis of a Cool Sound, although there’s nothing particularly revelatory about it.

I picked up the Paley and Barthelme when I swung by our campus library to get Don’t Hide the Madness, a series of conversations between Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. Burroughs is getting pretty close to the end of his life here, and Ginsberg seems to want to get him to further cement a cultural legacy through a late oral autobiography. Burroughs repeatedly derails these attempts though, which is hilarious. Burroughs talks about whatever comes to mind (often his guns). The cover by Robert Crumb is worth sharing:

I initially requested the Burroughs book because I’ve been rereading Cities of the Red Night—and absolutely loving it—and I was trying to figure out who it was who may or may not have played a role in ghostwriting the book with Burroughs. Cities is straighter than much of Burroughs’ work—but it’s still thoroughly Burroughsian. It’s entirely possible that a straighter hand cobbled Burroughs’ images and fragments together, at least to some extent, although I think it’s erroneous to refer to the novel as ghostwritten. As far as I can tell, the claim originates with Dennis Cooper’s obituary in the October 1997 issue of Spin:

My initial guess was that Cooper here insinuates that Victor Bockris helped arrange Cities of the Red Night. Bockris was around Burroughs a lot when Burroughs was working on Cities; however, Bockris suggests that it was Burroughs who corrected his prose:

From 1979 to 1981, I had the privilege of working with William Burroughs (aged sixty-five to sixty-seven) editing two books: my portrait With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker (St. Martins, 1996), and his selected essays, The Adding Machine (Arcade, 1996). At the same time, Burroughs was finishing his long-awaited novel, Cities of the Red Night (Holt, 1981), which would inaugurate a whole new person and period in his career, opening the doors to sixteen highly productive, positive years (1981-97) writing, painting, acting, performing, recording. Consequently, I suppose I am one of the ten to twelve people who ever got close enough to Bill professionally to see into his writing center. When I gave him the manuscript of With William Burroughs (75 percent of which was taped dialogue of conversations between Burroughs and fifteen other celebrities), he not only corrected the sometimes atrocious writing, he added a handful of precious inserts.

More digging seems to suggest that it was the artist Steven Lowe who helped Burroughs arrange Cities. Rick Castro’s appreciation of Lowe goes as far as to assert that, Lowe “was a ghostwriter for Burroughs, assisting on Cities of the Red Night, Junkie, and a few other titles.”

Ultimately, I agree with Jamie Russell in Queer Burroughs (2001), that

The rumor that the post-Red Night trilogy texts were partly ghostwritten is perhaps…more of a compliment than the criticism it was intended to be, since it highlights Burroughs’ central theme of the 1980s and 1990s texts: the creation of a post-corporeal real. Who needs a body to write with anyway?

Typing that out, I realize that I’ve inserted an entirely different post into this Sunday equinox post. Oh well.

I love Cities of the Red Night—it’s funny and gross and oddly sweet and even sentimental, an ironic pastiche of the so-called “boys books” genre, as well as a howl against war, conformity, and the military-industrial-entertainment complex. The novel it most reminds me of (apart from other Burroughs’ novels) is Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day.

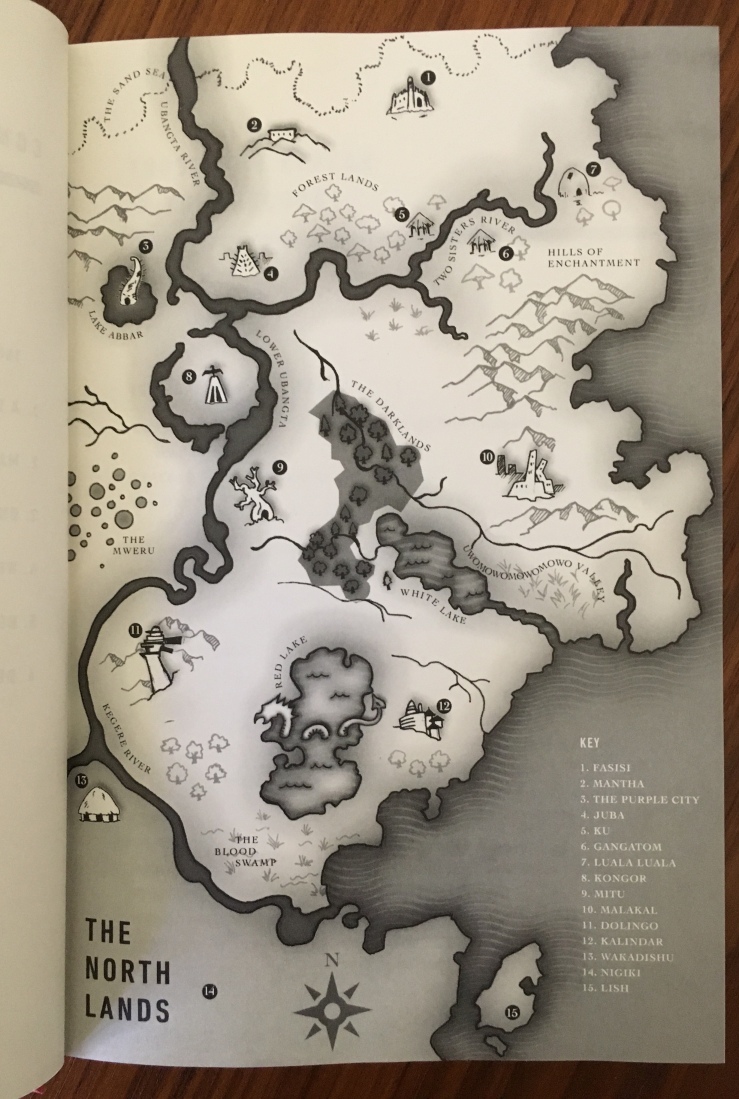

I’m also, thanks to the audiobook, into the third section of Marlon James’ Moon Witch, Spider King. The second section focused on the protagonist Sogolon’s domestic life. Frankly, the section sags, although I understand that it likely girds the emotional core of the events to come. The novel pivots dramatically in section three, “Moon Witch.” Sogolon has lost her memory, and is in a strange sunken city centuries in the future. That’s the good shit. More thoughts to come.