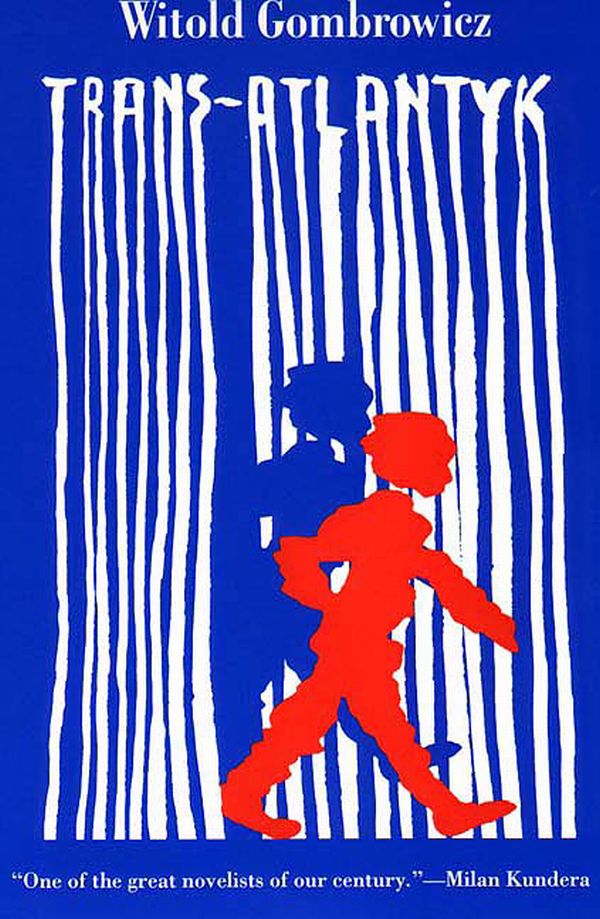

Witold Gombrowicz’s semi-autobiographical novel Trans-Atlantyk is a slim, bristling work that dances out over a mere 122 pages with a force that simultaneously exhausts and engages. Our hero is the eponymous Gombrowicz, a Polish intellectual who travels via pleasure cruise to visit Argentina. The ship arrives to the near-immediate news that the Nazis have occupied Poland. Most of the dutiful, patriotic Poles clamber back on the ship; Gombrowicz, doubling the real-life author, elects to stay in a self-imposed exile. None of the reasoning or rationale behind these decisions is made especially clear (indeed, I had to glean much of the reasoning for these events from the book’s introduction). Here is how the scene plays out in Gombrowicz’s strange syntax—

Then would I fain have fallen on my knees! Albeit I did not fall at all, just quietly began to Curse, Damn mightily but only to Myself: “Sail, sail, you Compatriots, to your People! Sail to that holy Nation of yours haply Cursed! Sail to that St. Monster Dark, dying for ages yet unable to die! Sail to your St. Freak, cursed by all Nature, ever being born and still Unborn! Sail, sail, so he will not suffer you to Live or Die but keep you for ever between Being and Non-being. Sail to your St. Slug that she may ever the more Enslime you.” The ship turned aslant now and was moving off so this I likewise say: “Sail to that Madman, to that St. Bedlamite of yours—oh, haply Cursed—so that he may Torment, Torture you by those leaps and frenzies of his, drown you in blood, howl at you and by his Howling howl you out, by Torturing torture you, Children of yours, wives, to Death, to Agony—in agony himself, in the agonies of Madness Madden you, O’ermadden you!” With this Curse, turning my back on the ship, I entered the Town.

The passage, which I encourage you, gentle reader, to read again (go ahead, I’ll wait), showcases much of Trans-Atlantyk’s strange power: the archaisms, the snaky syntax (Gombrowicz repeatedly delays his predicate verb or even his subject, burying them at the end of the sentence), the bizarre capitalization, the acid humor, the bloody pathos, the impossible tone. So many of the book’s conflicts are laid bare in this passage. We see the essential conflict of an individual vs. the culture and society that would claim him as its mouthpiece; we find Poland, “that St. Monster Dark,” that cursed “St. Slug” forever trailing behind the rest of Europe, playing out the fight between tradition and modernism; we find the conflict of the exile, projected through the distortion of a fun house mirror, smacking back on our narrator who himself is now cursed “for ever between Being and Non-being.”

Trans-Atlantyk was composed during and after WWII, and much of the madness inherent in its themes became normalized during this time. As if to call attention to these psychic disjunctions, Gombrowicz writes Trans-Atlantyk in the mode of the gawęda, an antiquated form of Polish folk narrative popular with the rural nobility. Gawęda, oral in scope and tradition, emphasizes inner-textual creation, randomness, digression, alliteration, and, above all, energetic narrative freeplay—features Trans-Atlantyk displays with remarkable force. Gombrowicz uses this idiom in a celebratory mode, showcasing the possibility and liveliness of language, but he also ironizes language itself: Trans-Atlantyk might be read as a sustained attack on Poland’s obsessions with archaic tradition, as well as an attack on patriotism and patriarchal authority in general. In the 1994 translation I read, Carolyn French and Nina Karsov render Gombrowicz’s pseudo-gawęda in a kind of 17th or 18th century English style—and they do so to grand effect. Their “Translator’s Note” is perhaps the most instructive piece of scholarship on how translation happens that I have ever read. It’s worth the price of admission alone. And while I do not possess the skills to read the book in its original Polish, I imagine that French and Karsov have accurately and faithfully telegraphed the spirit of Gombrowicz’s novel.

If we return briefly, kind reader, to the excerpt above, we find our hero penniless and cursed, heading into town. Here he finds an odd non-home among the Polish ex-pats, who humorously call the Argentinians “aliens.” (Gombrowicz repeatedly stages scenes that show the extreme disconnection between the Poles and their New World surroundings; it is as if these Europeans are unable to comprehend that they are in the midst of a culture other than their own). Unsure of what to do and fearing the stigma of being a traitor (and, honestly, broke), Gombrowicz heads to the Polish Legate, essentially to turn himself in, but also in the hopes of gaining some kind of employment. He meets with the Polish Minister in a scene that is hilarious but, in its historical irony, also shocking and sad. The Minister is something of a mouthpiece for the Polish attitude that Gombrowicz satirizes—

He drew a breath. Did flash his eye. Did say: “We will, by my troth. I say this to you, and I say this so you cannot say that I was saying that we would not Vanquish, since I say to you that we will Vanquish, will Win, for we will reduce to dust with our mighty, gracious hand—smash, crush to dust, powder, with Sabres, Lances, anatomize, annihilate, and under our Colours and in our Majesty, oh Jesus Maria, oh Jesus, oh Jesus . . . we will grind, Kill! Oh, we will kill, anatomize, demolish! And why are you staring so? I tell you indeed, we will annihilate! Indeed you can see, you can hear the Minister himself, the Gracious Envoy is telling you we will Annihilate; perchance you can see that the Envoy himself, the Minister, is pacing here before you, waving his hands and telling you that we will Annihilate! And don’t you dare bark thus: that I didn’t Pace before you, that I didn’t Say, as you see that I do Pace and Say!”

The minister’s phallic aggression, bound in two of the book’s motifs—walking and speaking—reveals the deep paranoia that seethes under the surface of the ex-pat community; indeed, it’s this very paranoia that drives Gombrowicz to the Legate in the first place. In any case, Gombrowicz soon finds a job as a bank clerk, although the specifics here are a bit murky. The real-life Gombrowicz worked as a bank clerk for years in Argentina, famously saying that the job gave him the freedom to write while his boss wasn’t looking. Thankfully, Trans-Atlantyk spends little time in its protagonist’s workplace, but I think it’s worth sharing one of the few passages about office life in the book. There’s a Kafkaesque scope to Gombrowicz’s observations about the modern office, an innate realization of the dehumanizing aspects inherent in bureaucracy, but also a strong vein of absurd humor—

Amidst these rustlings I slightly opened the door that led to the next Room. A big room, long and Darkish, and a row of tables at which clerks sit, over Promissory Notes, Ledgers, Folios studiously bent; and such a number of Papers, so lumped, Swamped that you can hardly move, for likewise on the floor there a multitude of papers and old scribblings; and Ledgers from a cupboard protrude and even to the ceiling heave, out onto the windowsills bulge and swamp the Office. So if any of the clerks moves, he rustles as a Mouse in these papers.

The description continues, Gombrowicz marking the ways in which the clerks remain at their desks even to eat. As the passage reaches its conclusion, the scene described might take place in any contemporary office—

Whereupon Tea was brought in, viz. Mugs with coffee and buns on a tray, and then all the clerks, having paused in their work, set upon the food. And anon, as usual, discourse sounded. I was overcome by laughter at the sight of that Coffee Drinking of those clerklets! Since at first sight one could see that, for years, sitting together in this Office, every day the eternal Coffee drinking and the eternal Bun munching, with these same old jokes treating themselves, they at once all there was of theirs was comprehended.

So much of contemporary life is there: its mundane rituals, its mechanical repetitions, its pathetic consolations. If Gombrowicz feels contempt for the idea that an individual owes a duty to society, that contempt extends right into the workplace.

Yet I’m barely scratching the surface here. The real plot of Trans-Atlantyk—and bear in mind, kind reader, that this plot hurtles or waltzes or jerks through its motions, rarely employing conventional narrative sequencing signals; rather, we have here a picaresque of sorts, a constant deferral of clear meaning—the real plot of Trans-Atlantyk (if such a thing exists) careens around a good old-fashioned duel. Somehow our hero falls into this intrigue, which results when a senior Polish man finds his honor assaulted. What assaults his honor? The lascivious intentions of a notorious and wealthy homosexual Argentinian on said senior Pole’s son. It’s easy here to frame the conflict in any number of dualities: Euorpean vs. New World, patriarchal tradition vs. homosexual outsider, familial order vs. alien anarchy. But there’s more to the conflict than mere duality. The homosexual Gonzalo, with his predatory designs on the Pole’s teenage son, comes to embody himself that core conflict of “Being and Non-being,” a figure whose conceptual impossibility reflexively engenders new and untold possibilities. Here’s our narrator’s description—

Ergo methinks: And what is’t? Where am I? What do I do? And from him would I have fled long ago, yet sorrowful sore was I to desert my only companion. For a Companion he was. Yet, when by the Tree he so together with me, I feel somewhat discomfited as neither Fish nor Fowl. Viz. hairs black, manly he had on his hand, but this hand—Dimpled, White, dainty Hand . . . and likewise perchance foot . . . and although a Cheek dark with shaven hairs, this Cheek of his charms and coquettes as if ’twere not Dark but indeed white . . . and likewise Leg though Manly as if ‘twould be a Dainty leg and Charms in curious caprices . . . and though head of a man in his prime, bald at the brow, Wrinkled, this head as if slips off a head, seeking to be a dainty head . . . So he as if fain would not himself Transforms in the silence of the night, and now you wit not whether ’tis He or She . . . and perchance, being neither this nor that, he has the aspect of a Creature and not a human . . . He lurks, the rascal, stands, says naught, and only at his Boy silently gazes. So I think, what the Devil, Werewolf, and wherefore I here with him . . .”

Notice how this in-betweener, this “Werewolf” recapitulates the perception of his own indeterminacy back on our narrator, who feels “discomfited as neither Fish nor Fowl.” This radical ambiguity plays out through the remainder of the novel, which alternately writhes, skips, and dances in an exploration of a world without fixed meaning, or, perhaps more accurately, a world where all meaning must be questioned, weighed not just in words and books but also in blood. Trans-Atlantyk ends in an explosion of radically ambiguous laughter, a gesture of hilarity and violence, joy and ridicule—it is a laughter that might claim the reader as its object or, perhaps, invite the reader to laugh along.

Trans-Atlantyk is a marvelous dare to readers, a work of language invention on par with the best in late modernism. Like any work that creates and enacts its own idiom, Trans-Atlantyk poses a learning curve that will doubtless frustrate or intimidate many readers. But its rewards are plentiful for those willing to trek through its anarchy and slip unresisting into its chaos. Recommended.