Hear Dmitry Samarov read the introduction to Georges Perec’s novel Life A User’s Manual.

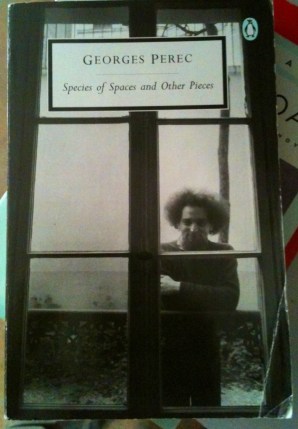

From “The Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books,” collected in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. English translation by John Surrock.

There are four paintings on the walls.

The first is a still life that despite its modern manner is strongly reminiscent of those compositions constructed on the theme of the five senses which were so common throughout Europe from the end of the Renaissance to the eighteenth century: on a table, there is an ashtray with a lighted Havana, a book of which the title and subtitle can be seen – The Unfinished Symphony: A Novel – though the name of the author is hidden, a bottle of rum, a cup-and-ball, and, in a shallow bowl, a pile of dried fruit, walnuts, almonds, apricot halves, prunes, etc.

The second depicts a street on the edge of a city, at night, alongside wasteland. To the right, a metal pylon with crossbars supporting at each point of intersection a large, lighted electric lamp. To the left, a constellation of stars reproduces precisely the inverse image of the pylon (base in the sky, apex towards the ground). The sky is covered in a flower pattern (dark blue on a lighter background) identical to the shapes made by frost on glass.

The third is of a legendary beast, the tarand, first described by Gelon the Sarmatian:

A tarand is an animal as big as a bullock, having a head like a stag, or a little bigger, two stately horns with large branches, cloven feet, hair long like that of a furred Muscovite, I mean a bear, and a skin almost as hard as steel armour. The Scythian said that there are but few tarands to be found in Scythia, because it varieth its colour according to the diversity of the places where it grazes and abides, and represents the colour of the grass, plants, trees, shrubs, flowers, meadows, rocks, and generally of all things near which it comes. It hath this in common with the sea-pulp, or polypus, with the thoes, with the wolves of India, and with the chameleon; which is a kind of lizard so wonderful, that Democritus hath written a whole book of its figure, and anatomy, as also of its virtue”“and property in magic. This I can confirm, that I have seen it change its colour, not only at the approach of things that have a colour, but by its own voluntary impulse, according to its fear or other affections: as for example, upon a green carpet, I have certainly seen it become green; but having remained there some time, it turned yellow, blue, tanned and purple, in course, in the same manner as you sec a turkey-cock’s comb change colour according to its passions. But what we find most surprising in this tarand is, that not only its face and skin, but also its hair could take whatever colour was about it.

The fourth picture is a black-and-white reproduction of a painting by Forbes called A Rat Behind the Arras. This painting was inspired by a true story which took place at Newcastle-upon-Tyne during the winter of 1858.

From Georges Perec’s novel Life A User’s Manual. English translation by David Bellos.

From Georges Perec’s “Reading: A Socio-Physiological Outline.” Collected in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces.

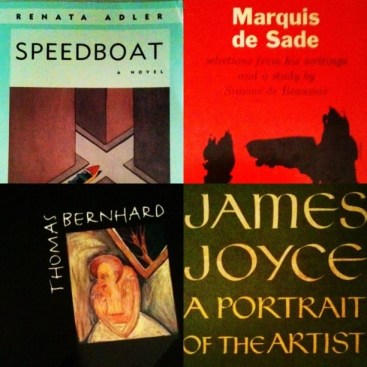

I picked up Georges Perec’s twofer Things and A Man Asleep last Friday at the used bookstore. I was there looking for something else. The Perec was not even shelved under “P.” I found it laid on a table. The good people at Melville House also sent me a copy of Perec’s La Boutique Obscure last week, which I do not photograph here because it is an ebook. I read a big chunk of Obscure this week and will do some kind of write-up sometime soon, but here’s David Auerbach’s review at the LA Review of Books in the meantime.

At the home of some good friends this past weekend, reclined nicely in a warm armchair, the warmth of various ales coursing through me, I picked off the shelf by my right hand a crumbling first edition of Modern Library’s A Comprehensive Anthology of Modern Poetry, edited by Conrad Aiken. I opened at random and found a small and perhaps undue joy that my stochastic flipping led to sections 10 and 11 of Song of Myself—maybe my favorite parts of Walt Whitman’s longassed poem.

Do you recall these bits? The trapper’s wedding? The runaway slave? The twenty-eight bathers and the woman who spies on them? I read them aloud to the room, ostensibly to the people in the room, but maybe just to myself. Walt Whitman’s storytelling is at its best when he moves most away from himself, when he puts on different hats, wears different ears, strolls around America a bit. I love his free verse in spite of—or even maybe because of—its swollen scope, its tendency toward bombast or even hamminess. O Walt! Get over yourself!—but not really, never change! Song of Myself is one of my favorite novels, or one of my favorite epics, or one of my favorite monologues—whatever it is, it’s one of my favorites (especially taken with doses of Emily Dickinson’s strange potions).

I don’t really know a lot about poetry, despite teaching the study of it in certain literature survey classes.

But hang on, it seems I was telling a story, or at least teasing out an anecdote, or at least going somewhere with all this: So, after riffling through the anthology a bit more, my friend says, Hey, if you want to read some really terrible poetry, check out that book to your right. Here is the book:

I had never heard of Walter Benton or his (unintentionally) hilarious volume This Is My Beloved until that moment. So what is it? Combining the worst elements of Whitmanesque free verse with a downright silly conceit that these are diary entries, This Is My Beloved attempts to be the erotic record of a passionate love affair. Benton tries to keep his language sultry, sexy, and sensuous without veering into pornography, but the results are bizarre and grotesque. Here’s an entire page as evidence:

“Your breasts are snub like children’s faces”?!

“…your lips match your teats beautifully”?!

And my favorite: “The hair of your arm’s hollow and where your thighs meet / agree completely, being brown and soft to look at like a nest of field mice.” A nest of field mice! Women love to be complimented on their matching pits and pubes, followed by a simile comparing said regions to a rodent’s hovel.

Indeed, Benton loves animal similes for his lady—later he writes: “Yes, your body makes eyes at me from every salient, / promises warm, lavish promises— / curved, colored . . . finished in a warm velvet like baby rabbits.”

But it’s not just the rabbits and mice that are gross. Lines like “We had loved hard—it’s all over your throat and hair” are simply queasy, bad writing. Or this nugget: “The white full moon like a great beautiful whore / solicits over the city, eggs the lovers on / the haves . . . walking in twos to their beds and to their mating. / I walk alone. Slowly. No hurry. Nobody’s waiting.”

Or this snippet:

It’s just really, really bad—I mean, at least when Henry Miller is gross, he’s deeply, earnestly gross, abject even, depraved perhaps (recall the famous lines: “I have set the shores a little wider. I have ironed out the wrinkles. After me you can take on stallions, bulls, rams, drakes, St. Bernards. You can stuff toads, bats, lizards up your rectum. You can shit arpeggios if you like, or string a zither across your navel”).

So, to return to my little story, we read most of Benton’s book aloud, doubling over laughing at times at just how wonderfully awful it is. And, wiping the tears from my eyes, I went to my trusty dusty iPhone to do a little background research—surely the world knew of this awful, awful poetry? Surely folks were getting the same giggly fun as happy we from poor Benton’s lurid verse?

And here, really, comes the occasion for this post, the real reason I write: It turns out that folks love this book—in a sincere, earnest, serious way. No fewer than four audio recordings were made of the book, all set to music (the most famous seems to be by Arthur Psyrock); the book has near-perfect five star review averages on both Amazon and Goodreads; and, perhaps most shocking of all, the book has been continuously in print since it was first published in 1949—it’s in its 34th edition (prestigious hardback with prestigious deckle edges, by the way). And of course you can buy an ebook version! (Unlike, say, Georges Perec’s Life A User’s Manual). Even worse, hack crooner Rod McKuen cites Benton as a major influence, so we have that to thank him for as well.

I don’t know. Am I wrong? Is Benton’s stuff actually good? I mean, I’ll concede that I enjoyed reading the book, but only inasmuch as it made me laugh so much. I don’t know. I already admitted I don’t know much about poetry. (As I write this, I pause to watch and listen to Richard Blanco read his inauguration poem “One Day”; I have no idea if it’s good or not). Benton’s verse seems so hammy, clumsy, indelicate; too earnest, too priapic, tripping over its own boners. It reads like a bad cribbing of Whitman and Miller, with an occasional lift from Hemingway. Even worse, it strikes me as amateurish, as the sort of thing that a teen might scrawl in his Moleskine only to cringe at later before hiding it somewhere. I just can’t believe that this book has been in continual publication from a major house (Knopf) for more than a half-century.

But maybe I’m misreading. Maybe I’m cynical. Maybe the poem is beautiful and profound and not icky solipsistic dreck. But I doubt it.

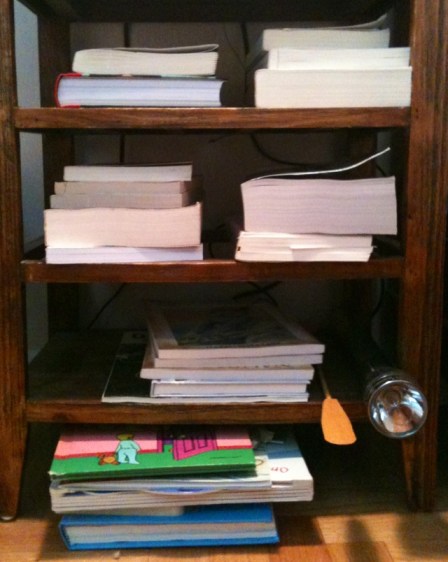

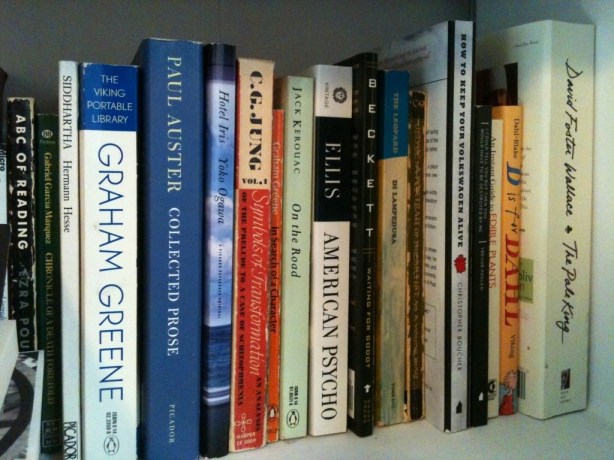

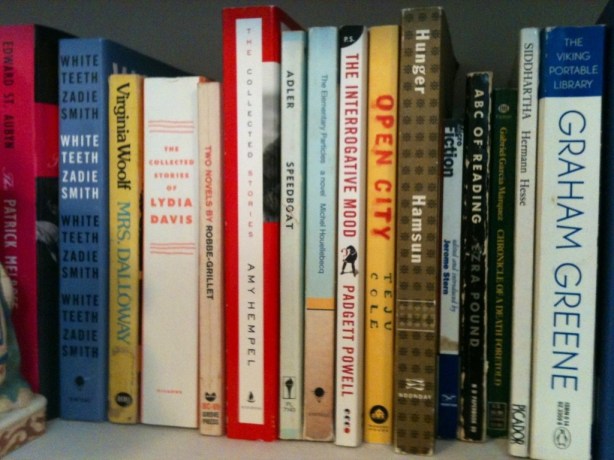

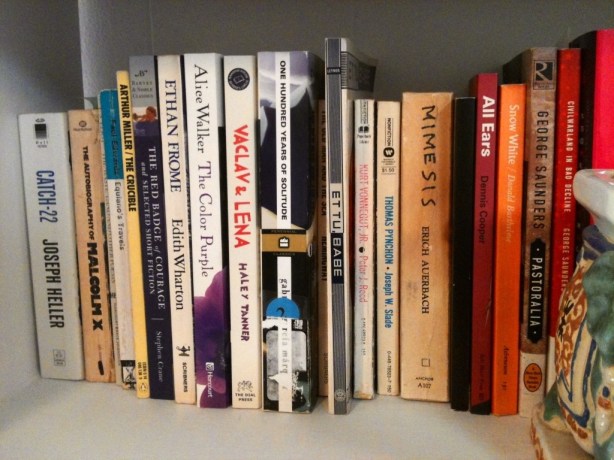

Book shelves series #53, fifty-third—and final!—Sunday of 2012: In which I take a few photos at random.

I somehow managed to squeeze 52 weeks of shots out of all the book-bearing surfaces of my home (—oh—I did one week from my office).

For the last in this series (yay!) I simply walked through the rooms of the house, took a few shots, and then put them in digital frames.

For the most part, my method was thoughtless, although I did grab a pic of a bookcase new to our house (second pic, top left) that dominates my son’s room.

I also took a pic of Perec’s essay collection because one of his essays inspired this (awful, awful) project.

From that essay, “The Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books”:

We should first of all distinguish stable classifications from provisional ones. Stable classifications are those which, in principle, you continue to respect; provisional classifications are those supposed to last only a few days, the time it takes for a book to discover, or rediscover, its definitive place. This may be a book recently acquired and not read yet, or else a book recently read that you don’t quite know where to place and which you have promised to yourself you will put away on the occasion of a forthcoming ‘great arranging’, or else a book whose reading has been interrupted and that you don’t to classify before taking it up again and finishing it, or else a book you have used constantly over a given period, or else a book you have taken down to look up a piece of information or a reference and which you haven’t yet put back in its place, or else a book that you can’t put back in its place, or else a book that you can’t put back in its rightful place because it doesn’t belong to you and you’ve several times promised to give it back, etc.

So, what did I get out of doing this project?

1. Photographing books is difficult—I mean physically. They all reflect light differently.

2. Doing a regularly-scheduled project is difficult.

3. I have too many books.

Okay. That’s it. Finis.

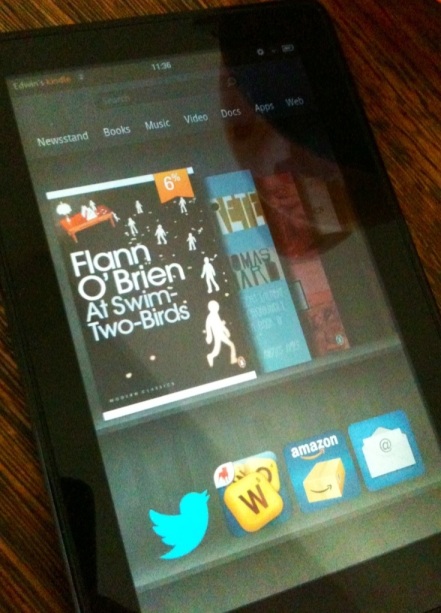

Book shelves series #52, fifty-second Sunday of 2012: In which, in this penultimate chapter, we return to the site of entry #1.

The first entry in this project was my bedside nightstand. This is what it looked like back in January:

This is it this morning:

This is the major difference:

The Kindle Fire has changed my late night shuffling habits.

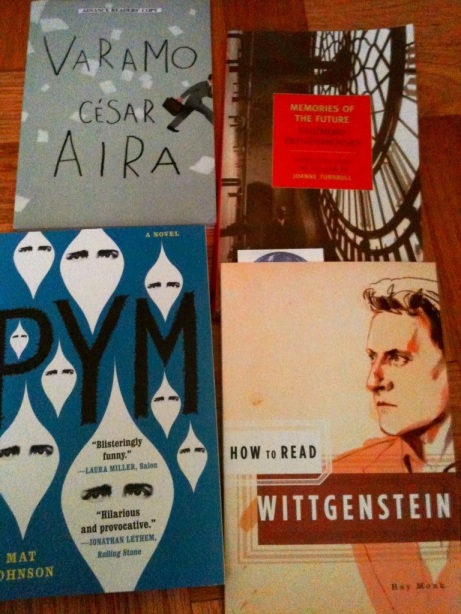

Here are the books that are in the nightstand:

I read the Aira novel but completely forgot about it, which I’m sure says more about me than it.

Have no idea why this is in there:

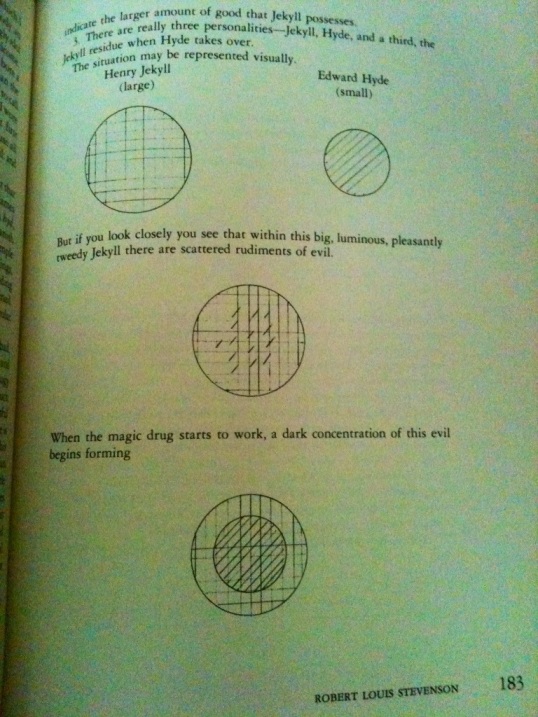

But it’s a fun book. With pictures! Sample:

Finally, Perec’s Life A User’s Manual—this is one of my reading goals for 2013. It seems like a good way to close out this penultimate post, as one of Perec’s essays inspired this project

“Every library answers a twofold need, which is often also a twofold obsession: that of conserving certain objects (books) and that of organizing them in certain ways”

—Georges Perec, from ”Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books” (1978)

Book shelves series #46, forty-sixth Sunday of 2012

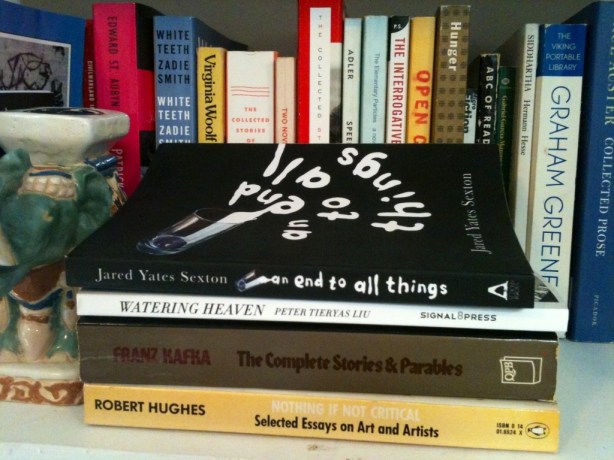

Another double-stacked shelf. This one even has a stack of drifters.

This shelf is at my eye/arm level, and looking at it this way, I see that it gets a lot of shuffling—I can see where I started certain projects for the site.

I can see books that are in line, so to speak, for either proper shelving or for reading.

The mounding stack on the shelf below is a bit out of control, although most of what sits there comes from other places (I kinda sorta wrote about those here).

Below: Unsorted stuff that I’ve been reading of an afternoon:

This is the front stack—books that need proper shelving elsewhere, books that I’ve read (and sometimes reviewed here) in the past few months, or meant to read, or in some other way consulted or read from:

The far right side of the shelf—again, a very mixed bag. I think I originally intended to properly shelf everything here and then got sidetracked:

Moving left:

And here’s what’s behind the front stack—okay, I can see now the edges of an idea I had for shelving; I also see where I just abandoned that idea:

This whole project I blame on an essay by Georges Perec, collected in this one:

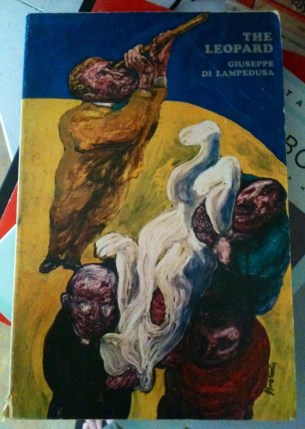

This is one of my favorite book covers:

More covers I like from this shelf: