I’m leaving to (finally) see Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Inherent Vice in a few minutes.

I’m going with my uncle. (I also saw No Country for Old Men with him in the theater. This point seems hardly worth these parentheses).

Below, in block quotes, is my review of Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice (which I published here—the review obviously—in 2009). My 2015 comments are interposed.

Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Inherent Vice

Oh god I used to bold face key terms jesus christ sorry.

is a detective-fiction genre exercise/parody set in a cartoonish, madcap circa-1970 L.A. redolent with marijuana smoke, patchouli, and paranoia.

“genre exercise”…”madcap”…ugh!

Navigating this druggy haze is private detective Doc Sportello, who, at the behest of his ex-girlfriend, searches for a missing billionaire in a plot tangled up with surfers, junkies, rock bands, New Age cults, the FBI, and a mysterious syndicate known as the Golden Fang–and that’s not even half of it.

Not a bad little summary, bro.

At a mere 369 pages, Inherent Vice is considerably shorter than Pynchon’s last novel Against the Day, not to mention his masterpieces Gravity’s Rainbow and Mason & Dixon, and while it might not weigh in with those novels, it does bear plenty of the same Pynchonian trademarks: a strong picaresque bent, a mix of high and low culture, plenty of pop culture references, random sex, scat jokes, characters with silly names (too many to keep track of, of course), original songs, paranoia, paranoia, paranoia, and a central irreverence that borders on disregard for the reader.

Uh…

And like Pynchon’s other works, Inherent Vice is a parody, a take on detective noir, but also a lovely little rip on the sort of novels that populate beaches and airport bookstores all over the world. It’s also a send-up of L.A. stories and drug novels, and really a hate/love letter to the “psychedelic 60s” (to use Sportello’s term), with much in common with Pynchon’s own Vineland (although comparisons to Elmore Leonard, Raymond Chandler, The Big Lebowski and even Chinatown wouldn’t be out of place either).

When I heard the PTA was adapting Inherent Vice, I thought: Wait, the Coens already did that before Pynchon wrote the book.

While most of Inherent Vice reverberates with zany goofiness and cheap thrills,

Clichés, bro.

Pynchon also uses the novel as a kind of cultural critique, proposing that modern America begins at the end of the sixties (the specter of the Manson family, the ultimate outsiders, haunts the book). The irony, of course–and undoubtedly it is purposeful irony–is that Pynchon has made similar arguments before: Gravity’s Rainbow locates the end of WWII as the beginning of modern America; the misadventures of the eponymous heroes of Mason & Dixon foreground an emerging American mythology; V. situates American place against the rise of a globally interdependent world.

Uh…

If Inherent Vice works in an idiom of nostalgia, it also works to undermine and puncture that nostalgia. Feeling a little melancholy, Doc remarks on the paradox underlying the sixties that “you lived in a climate of unquestioning hippie belief, pretending to trust everybody while always expecting be sold out.” In one of the novel’s most salient passages–one that has nothing to do with the plot, of course–Doc watches a music store where “in every window . . . appeared a hippie freak or a small party of hippie freaks, each listening on headphones to a different rock ‘n’ roll album and moving around at a different rhythm.” Doc’s reaction to this scene is remarkably prescient:

. . . Doc was used to outdoor concerts where thousands of people congregated to listen to music for free, and where it all got sort of blended together into a single public self, because everybody was having the same experience. But here, each person was listening in solitude, confinement and mutual silence, and some of them later at the register would actually be spending money to hear rock ‘n’ roll. It seemed to Doc like some strange kind of dues or payback. More and more lately he’d been brooding about this great collective dream that everybody was being encouraged to stay tripping around in. Only now and then would you get an unplanned glimpse at the other side.

Oh cool you finally quoted from the book. Not a bad little riff.

If Doc’s tone is elegiac, the novel’s discourse works to undercut it, highlighting not so much the “great collective dream” of “a single public self,” but rather pointing out that not only was such a dream inherently false, an inherent vice, but also that this illusion came at a great price–one that people are perhaps paying even today. Doc’s take on the emerging postmodern culture is ironized elsewhere in one of the book’s more interesting subplots involving the earliest version of the internet. When Doc’s tech-savvy former mentor hips him to some info from ARPANET – “I swear it’s like acid,” he claims – Doc responds dubiously that “they outlawed acid as soon as they found out it was a channel to somethin they didn’t want us to see? Why should information be any different?” Doc’s paranoia (and if you smoked a hundred joints a day, you’d be paranoid too) might be a survival trait, but it also sometimes leads to this kind of shortsightedness.

Will PTA’s film convey the ironies I found here? Or were the ironies even there?

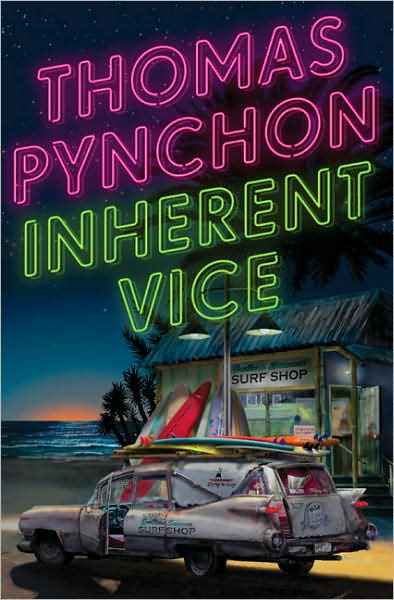

Intrinsic ironies aside, Inherent Vice can be read straightforward as a (not-so-straightforward) detective novel, living up to the promise of its cheesy cover. Honoring the genre, Pynchon writes more economically than ever, and injects plenty of action to keep up the pace in his narrative. It’s a page-turner, whatever that means, and while it’s not exactly Pynchon-lite, it’s hardly a heavy-hitter, nor does it aspire to be.

I’m not sure if I believe any of that, bro. Did I believe it even when I wrote it? It’s a shaggy dog story, and shaggy dogs unravel, or tangle, rather—they don’t weave into a big clear picture. And maybe it is a heavy hitter. (Heavy one-hitter).

At the same time, Pynchon fans are going to find plenty to dissect in this parody, and should not be disappointed with IV‘s more limited scope (don’t worry, there’s no restraint here folks–and who are we kidding, Pynchon is more or less critic-proof at this point in his career, isn’t he?). Inherent Vice is good dirty fun, a book that can be appreciated on any of several different levels, depending on “where you’re at,” as the hippies in the book like to say. Recommended.

Oh geez.

Okay, I should write more but my uncle says it’s time to roll.