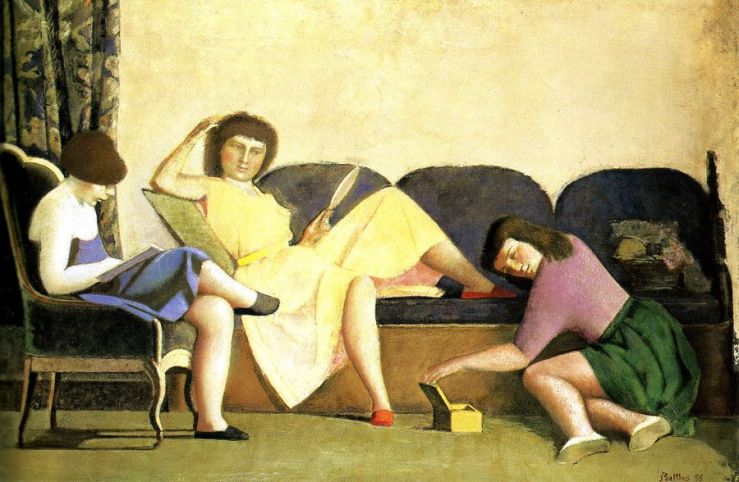

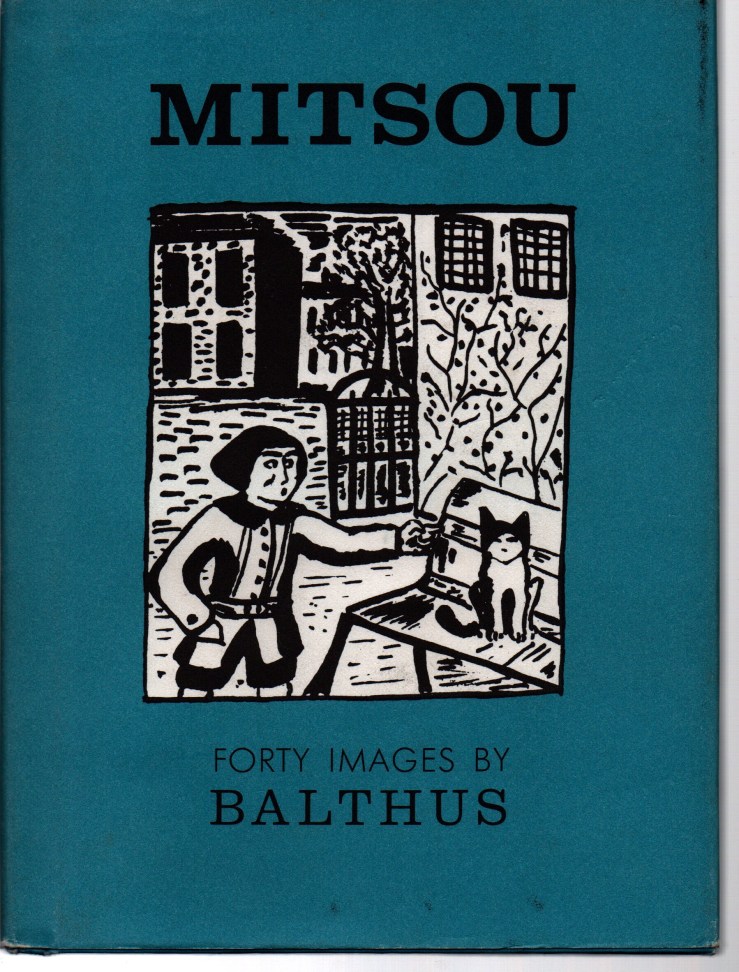

My young girls who read in dreaming poses are escaping from fleeting, harmful time: Katia, Frederique, and The Three Sisters. Fixing them in the act of reading or dreaming prolongs a privileged, splendid, and magic glimpsed-at time. A suddenly opened curtain sheds light from a window and is seen only by those who know how. Thus a book is a key to open a mysterious trunk containing childhood scents; we rush to open it like the child with butterflies, or the young girl with a moth. It is a gold-sprinkled time that avoids worldly alteration, time nimbused by a magic halo, time fixed in terms of what the smiling, dreaming girls see. It is surreal time in the true sense of the term.

—From Balthus’ 2001 memoir Vanished Splendors, “as told to” Alain Vircondelet. English translation by Benjamin Ivry.

The first Balthus painting I saw was The Bedroom. I saw it in Edward Lucie-Smith’s Movements in Art since 1945. I was maybe 17, and I found the painting not so much shocking as disturbing. It upset something in me, but I also found myself enchanted by it. In the painting an aesexual woman of dwarfish proportions, scowling and stern, pulls a black curtain to its side to allow sunlight to flood over the nude body of a young woman whose posture is simultaneously sexually vibrant and alarmingly comatose. A cat perched on a book glances out the window. There’s a dark fairy tale embedded in the painting. In its color, light, staging, subject, and theme, it’s of a piece with much of Balthus’ work. I didn’t know that over 20 years ago when I first saw it, but I did know that it intrigued me. I wanted to see more.

As a teenager, Balthus’ visions disturbed and engaged me. My response was aesthetic, but I also found a narrative even in his most static paintings. There’s an eerie peace to his reading girls that I saw then and see now. The rooms he painted were little dreams.

Now that I am older I find Balthus’ depictions of girls far, far more disturbing than I did two decades ago. Or rather, I find his paintings disturbing in a different way.

(I think here of rereading Lolita as an adult. I think I first read the book at 15 or 16, and was floored by its language; I read it again in my early 20s—and then in my late twenties. It was a different book).

And yet when I look at Balthus’ paintings of girls reading what emanates most strongly for me is that “gold-sprinkled time that avoids worldly alteration, time nimbused by a magic halo.” He captures something about the private world of reading that I identify with—what I mean is that I feel the feeling of the girls who read in his paintings.

Elsewhere in his memoir, Balthus declares—

…I completely reject the erotic interpretations that critics and other people have usually made of my paintings. I’ve accomplished my work, paintings and drawings, in which undressed young girls abound, not by exploiting an erotic vision in which I’m a voyeur and surrender unknowingly (above all, unknowingly) to some maniacal or shameful tendencies, but by examining a reality whose profound, risky, and unpredictable unreadability might be shed, revealing a fabulous nature and mythological dimension, a dream world that admits to its own machinery.

Balthus here gives us a fitting description of the “unreadability” of the visions he depicts. Key here is that both his negation (“not by”) and its parallel divergent conjunction (“but by”) frame a perfectly apt analysis of his own work—he is a voyeur, yes, and ushers in a voyeuristic eye—but he also stages a dream world that his viewers can feel.

Unclothe Hercules, 2015 by Xiao Guo Hui (b. 1969)

Unclothe Hercules, 2015 by Xiao Guo Hui (b. 1969)

Man after Man by Dougal Dixon with illustrations by Philip Hood. First edition hardback from St. Martin’s Press, 1990. Book design by Ben Cracknell; cover art by Philip Hood. It’s Hood’s illustrations that make Dixon’s “future anthropology” of the human race so fascinating. A discursive sci-fi novel of sorts, posing as a textbook.

Man after Man by Dougal Dixon with illustrations by Philip Hood. First edition hardback from St. Martin’s Press, 1990. Book design by Ben Cracknell; cover art by Philip Hood. It’s Hood’s illustrations that make Dixon’s “future anthropology” of the human race so fascinating. A discursive sci-fi novel of sorts, posing as a textbook.