I finished Martin Bax’s surreal dystopian romance The Hospital Ship last night and then finished the audiobook version of Margaret Atwood’s hyperreal dystopian anti-romance The Year of the Flood today. Both books take their cues from that first apocalypse story, the story of Noah and his ark, and continue that tradition imagining a version of the end of the world. Despite their mythical-biblical origins, such books tend to get ghettoized into a certain genre of science fiction — let’s call it apocalypse fiction — despite the artistic power or literary merit of the author’s prose itself. Apocalypse books like Kurt Vonnegut’s satire Cat’s Cradle, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and Aldous Huxley’s Ape and Essence diverge in style, tone, and execution. It’s their subject that compels us, each vision a proposition, a promise of some kind of future, a future after the future. Many of these apocalypse books remain prescient today. However, others feel dated simply because so much of what the author wrote twenty or fifty or more years ago more or less came true. For instance, is the homogenized, greenzoned aristocracy of Brave New World who lavish in the trivial culture of the feelies and centrifugal bumblepuppy all that different from contemporary exurbanites who basically live in walled-off compounds, little homogenized townships that strive to exist outside of civic reality and history? Robert Siegel’s recent report for NPR on the The Villages, an eerie Florida compound for senior citizens, illustrates how willing people are to buy into a company-owned, company-governed greenzone. The Villages even has its own whimsical fake “history,” complete with markers and plaques. It’s like The Prisoner or something. But enough about real life. We have apocalypse lit to tell us about the present.

The heroes of Atwood’s The Year of the Flood are not, for the most part, from the corporate-controlled compounds that keep the rest of the world at bay. There’s Toby, the orphan who grows up tough yet learns the healing arts. There’s Ren, a young girl trying to find her identity wherever she can. There’s their would-be spiritual guide, Adam One, and his lieutenant/rival Zeb. They are outsiders, members of an eco-cult called The Gardeners who worship saints like Rachel Carson, Ernest Shackleton, and Sojourner Truth. Flood is the sprawling companion to Atwood’s 2003 novel, Oryx and Crake, which I enjoyed very much. Both take place in a world where the “Waterless Flood,” a SARS/mega-flu type virus brought about via genetic tinkering, has turned most people into zombie-goo. I could go and on about the world Atwood shapes here, one full of genetic modification, eco-terrorism, religious fervor, and radical disparity, but other folks have already done it. So, in the grand tradition of internet laziness, I point you to excellent reviews here and here, which do a better job explicating the plot than I’m willing to do now (and it was an audiobook, remember, so I don’t exactly have it in front of me. Mea culpa). Apocalypse lit isn’t so much predictive as it is descriptive of the contemporary world, and Atwood’s dystopian vision is no exception. Viscerally prescient, Flood paints our own society in bold, vibrant colors, magnifying the strange relationships with nature, religion, and our fellow humans that modernity prescribes. Atwood ends her book in media res, with Toby and a handful of other characters somehow still alive, ready, perhaps, to become stewards of a new world. Flood concludes tense and, in a sense, unresolved, but Atwood implies hope: Toby will lead her small group to cultivate a new Eden. Despite all the ugliness and cruelty and devastation, people can be redeemed. The audiobook rendition of The Year of the Flood is very good, employing three actors to play the three principal roles, Ren, Toby, and Adam One. There are also terribly cheesy full-band versions of the hippy-dippy songs the Gardeners like to sing on certain Saint Days that are witty as parody but ultimately distracting. Atwood’s prose sometimes relies on placeholders and stock expressions common to sci-fi and YA fiction, and her complex plot (disappointingly) devolves to a simple adventure story in the end, but her ideas and insights into what our society might look like in a few decades are compelling reading (or, uh, listening in this case). Recommended.

The heroes of Atwood’s The Year of the Flood are not, for the most part, from the corporate-controlled compounds that keep the rest of the world at bay. There’s Toby, the orphan who grows up tough yet learns the healing arts. There’s Ren, a young girl trying to find her identity wherever she can. There’s their would-be spiritual guide, Adam One, and his lieutenant/rival Zeb. They are outsiders, members of an eco-cult called The Gardeners who worship saints like Rachel Carson, Ernest Shackleton, and Sojourner Truth. Flood is the sprawling companion to Atwood’s 2003 novel, Oryx and Crake, which I enjoyed very much. Both take place in a world where the “Waterless Flood,” a SARS/mega-flu type virus brought about via genetic tinkering, has turned most people into zombie-goo. I could go and on about the world Atwood shapes here, one full of genetic modification, eco-terrorism, religious fervor, and radical disparity, but other folks have already done it. So, in the grand tradition of internet laziness, I point you to excellent reviews here and here, which do a better job explicating the plot than I’m willing to do now (and it was an audiobook, remember, so I don’t exactly have it in front of me. Mea culpa). Apocalypse lit isn’t so much predictive as it is descriptive of the contemporary world, and Atwood’s dystopian vision is no exception. Viscerally prescient, Flood paints our own society in bold, vibrant colors, magnifying the strange relationships with nature, religion, and our fellow humans that modernity prescribes. Atwood ends her book in media res, with Toby and a handful of other characters somehow still alive, ready, perhaps, to become stewards of a new world. Flood concludes tense and, in a sense, unresolved, but Atwood implies hope: Toby will lead her small group to cultivate a new Eden. Despite all the ugliness and cruelty and devastation, people can be redeemed. The audiobook rendition of The Year of the Flood is very good, employing three actors to play the three principal roles, Ren, Toby, and Adam One. There are also terribly cheesy full-band versions of the hippy-dippy songs the Gardeners like to sing on certain Saint Days that are witty as parody but ultimately distracting. Atwood’s prose sometimes relies on placeholders and stock expressions common to sci-fi and YA fiction, and her complex plot (disappointingly) devolves to a simple adventure story in the end, but her ideas and insights into what our society might look like in a few decades are compelling reading (or, uh, listening in this case). Recommended.

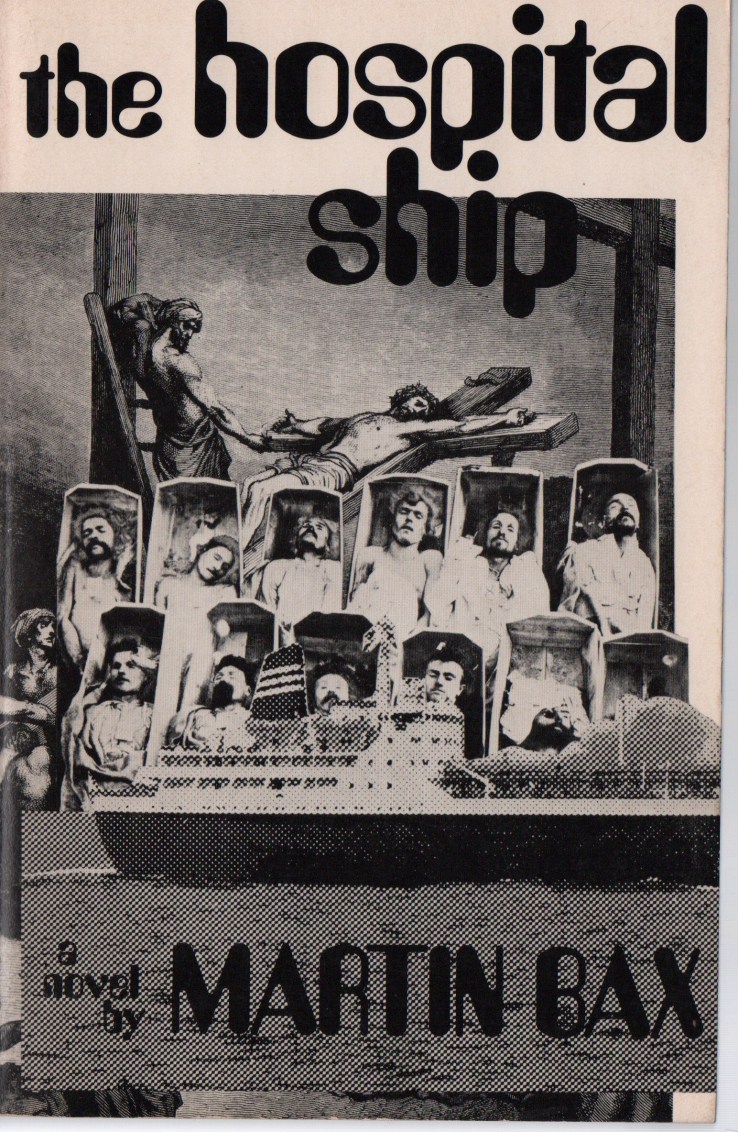

The doctors, specialists, sailors, and patients of the titular vessel in Martin Bax’s The Hospital Ship are afloat in their own greenzone of sorts, a moving compound that seeks to treat the troubled world. What’s the trouble with the world? No one’s sure, exactly–there’s permanent all-out-war, of course, famine perhaps, insanity for sure. There’s also a bizarre army of bureaucrats going from continent to continent crucifying men and raping women for no clear reason. The ship’s psychiatrists diagnose it “The Crucifixion Disease.” Euan, Bax’s erstwhile lead, tries to figure out how to love and how to heal in the middle of hate and extinction. Aided by the eccentric, Falstaffian Dr. Maximov Flint, Euan conducts an experimental therapy between a Moi prostitute named V and a suicidal Wall Street broker named W. He also finds a lover and partner in an American girl named Sheila. About half of The Hospital Ship comprises citations from a variety of non-fiction texts, including medical textbooks, psychiatric studies, sociology texts, travelogues, war diaries, and more. The technique is bizarre and jarring, and Bax often imitates the style of such texts, most of which linger on sex or death. There’s also an obsession with the Vietnam War, which makes sense as the book was published in 1976. There’s a lovey-hippie type vibe to the hospital ship’s personnel, and like Atwood with her Gardeners, Bax is satirical and loving to his heroes at the same time. He mocks some of the silly idealism of the movement even as he finds solace in their vision of love and healing in an apocalyptic world. Bax’s book is wholly weird, disconnected, lurching and farcical, a madcap dystopian Love Boat on peyote. I spotted it at my favorite used bookstore, intrigued first by the (now retro-)futurist font, then the name, echoing Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, another book about a hospital-as-ark. If the black-and-white collage cover art didn’t seal the deal, then the blurb from J.G. Ballard comparing Bax favorably to William Burroughs did. Burroughs is an appropriate reference point, with the sexual alienation and the medical flavor and the cut-up technique and all, but Bax’s writing is utterly Ballardian (he even directly cites Ballard among other authors–like, you know APA style in-text citations). The Hospital Ship is a cult novel which might not have a big enough cult. It definitely belongs in print again; until then, pick up a copy if you can find one.

The doctors, specialists, sailors, and patients of the titular vessel in Martin Bax’s The Hospital Ship are afloat in their own greenzone of sorts, a moving compound that seeks to treat the troubled world. What’s the trouble with the world? No one’s sure, exactly–there’s permanent all-out-war, of course, famine perhaps, insanity for sure. There’s also a bizarre army of bureaucrats going from continent to continent crucifying men and raping women for no clear reason. The ship’s psychiatrists diagnose it “The Crucifixion Disease.” Euan, Bax’s erstwhile lead, tries to figure out how to love and how to heal in the middle of hate and extinction. Aided by the eccentric, Falstaffian Dr. Maximov Flint, Euan conducts an experimental therapy between a Moi prostitute named V and a suicidal Wall Street broker named W. He also finds a lover and partner in an American girl named Sheila. About half of The Hospital Ship comprises citations from a variety of non-fiction texts, including medical textbooks, psychiatric studies, sociology texts, travelogues, war diaries, and more. The technique is bizarre and jarring, and Bax often imitates the style of such texts, most of which linger on sex or death. There’s also an obsession with the Vietnam War, which makes sense as the book was published in 1976. There’s a lovey-hippie type vibe to the hospital ship’s personnel, and like Atwood with her Gardeners, Bax is satirical and loving to his heroes at the same time. He mocks some of the silly idealism of the movement even as he finds solace in their vision of love and healing in an apocalyptic world. Bax’s book is wholly weird, disconnected, lurching and farcical, a madcap dystopian Love Boat on peyote. I spotted it at my favorite used bookstore, intrigued first by the (now retro-)futurist font, then the name, echoing Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, another book about a hospital-as-ark. If the black-and-white collage cover art didn’t seal the deal, then the blurb from J.G. Ballard comparing Bax favorably to William Burroughs did. Burroughs is an appropriate reference point, with the sexual alienation and the medical flavor and the cut-up technique and all, but Bax’s writing is utterly Ballardian (he even directly cites Ballard among other authors–like, you know APA style in-text citations). The Hospital Ship is a cult novel which might not have a big enough cult. It definitely belongs in print again; until then, pick up a copy if you can find one.