- I first read Russell Hoban’s 1980 post-apocalyptic quasi-religious coming-of-age novel Riddley Walker in maybe 1996 or 1997, when I was sixteen or seventeen, or possibly eighteen.

- That was the right age to read Riddley Walker for the first time, although I think anyone of any age, for the most part, could read Riddley Walker, if they want.

- This is not a review of Riddley Walker, but here is a nice summary from Benjamin DeMott’s 1981 NYT’s review:

-

Set in a remote future and composed in an English nobody ever spoke or wrote, this short, swiftly paced tale juxtaposes preliterate fable and Beckettian wit, Boschian monstrosities and a hero with Huck Finn’s heart and charm, lighting by El Greco and jokes by Punch and Judy. It is a wrenchingly vivid report on the texture of life after Doomsday.

-

The setting is near what was known – until 1997, when cataclysms wiped us out – as Canterbury, England. It is about 2,000 years after that disaster. The mostly dim lights of human life who survive are slaves to the obsessions of their invisible rulers. From generation to generation, they labor ceaselessly, under close surveillance, to disinter by hand the past that lies buried beneath tons of muck – mangled machines, mysteriously preserved bits of flesh, indecipherable fragments of writing. The rulers dream of uncovering the secret of secrets – the key to the power that enabled the giants of yesteryear to create a world in which boats sailed in the air and pictures moved on the wind.

- If the plot of Riddley Walker seems a trickle familiar it of course is. It’s been warmed up and reserved many times (and wholesale ripped off in the third Mad Max Max film). (It’s good eating.)

- But the novel still feels fresh (and grimy!) because of Hoban’s electrifying prose. Young Riddley’s narration is odd and alienating, even if, in, say, 2023, the novel’s premise seems worn.

- Back in the halcyon nineteennineties, when the world seemed generally less apocalpytic, a very good friend of mine loaned me his copy of Riddley Walker.

- I never gave it back.

- (Somehow, he still gives me books.)

- I too lost the first copy of Riddley Walker that I read. I loaned it to a student who never returned it, or Dune, or The Left Hand of Darkness, or a bunch of other sci-fi novels, god keep his soul.

- Riddley Walker was one of the first novels I wrote about on this silly website, way back in 2006. It wasn’t a review, it was about book theft.

- I had no plan to reread Riddley Walker, but here’s what happened—

- —I had finished reading Ian Banks’s odd coming-of-age novel The Wasp Factory—

- —and I had and have been listening to the audiobook of T.H. White’s Arthur saga, a return perhaps inspirited by—

- —reading Jim Dodge’s alchemical-grail-quest-coming-of-age novel Stone Junction—

- —and really, there were a lot of coming-of-age novels I seemed to get into this year:

- —Trey Ellis’s postmodern polyglossic satire Platitudes—

- —Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations and Blood and Guts in High School—

- —Henri Bosco’s The River and the Child—

- —Bernardo Zanonni’s picaresque My Stupid Intentions—

- —and Cormac McCarthy’s coming-of-age novel The Crossing—

- And so well and anyway, I was reading a novel in bed, my eyes working overtime, they’re older now, lenses over them but still there’s never enough light. I was reading this novel, it doesn’t matter what novel, but there was this little weird urge, germinating from the reading of the novels I mentioned above, asking me to Go pick up Riddley Walker again and check in.

- So I went and found my copy of Riddley Walker.

- It was not, obviously, the copy that I stole from my good friend that was later stolen from me.

- I’m not sure when I picked up this particular copy of Riddley Walker, but I’m thinking it was around 2008 or 2009.

- I think that’s when I read the other Hoban novels that I’ve read: The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz; Kleinzeit; Pilgermann.

- Of these three novels, Pilgermann is the best and most fucked up.

- (I like Kleinzeit, but it’s too indebted to Beckett.)

- Well so and anyway, I put down the novel I had been trying to read, and dug up Riddley Walker, put the thing under my poor old lensed eyes.

- Here are the first two paragraphs of Russell Hoban’s novel Riddley Walker:

-

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen. He dint make the groun shake nor nothing like that when he come on to my spear he wernt all that big plus he lookit poorly. He done the reqwyrt he ternt and stood and clattert his teef and made his rush and there we wer then. Him on 1 end of the spear kicking his life out and me on the other end watching him dy. I said, ‘Your tern now my tern later.’ The other spears gone in then and he wer dead and the steam coming up off him in the rain and we all yelt, ‘Offert!’ The woal thing fealt jus that littl bit stupid. Us running that boar thru that las littl scrump of woodling with the forms all roun. Cows mooing sheap baaing cocks crowing and us foraging our las boar in a thin grey girzel on the day I come a man.

- I think this is probably the fifth time I’ve read Riddley Walker. I have a very distinct memory of using the novel as the basis for a project in a linguistics class in college. The project had something to do with graphemes and phonemes and was very harebrained, and I am lucky, as always, that the internet was an infant at the time. (I got a “B” on the project and recycled it my senior year in an English class, getting (earning?) an “A.”)

- The previous point is a way of protesting that, even as familiar as I was and perhaps am with Riddley Walker’s linguistic barrier, I still found rereading it physically exhausting.

- (I am older now, and all reading tires my body in ways I didn’t expect would be possible even five years ago.)

- I also find myself putting the book down to chase rabbits down internet holes that simply weren’t available to me the last times I read the book—

- —reading variations of the legend of St. Eustace or mapping Hoban’s Riddley Walker map to contemporary England—

- —or just getting hung up on particular phrases and images, letting them rattle around. (And now wishing I’d underlined them so as to share them here, which I didn’t, underline them that is.)

- Riddley himself is far more arrogant and decisive than I’d remembered; the angst here is more about a great becoming of a world to come than it is a becoming into the self of adulthood.

- (Whatever the fuck that last phrase means; sorry.)

- I find myself with new connections too—Aleksei German’s 2013 film adaptation of the Strugagtski’s novel Hard to Be a God comes readily to mind, as does Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 film Children of Men.

- And David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas, too (along with the Wachowskis’ film adaptation), which stole readily from Riddley Walker.

- The bookmark at the back of the copy of Riddley Walker I opened was a postcard from Mexico from Texas:

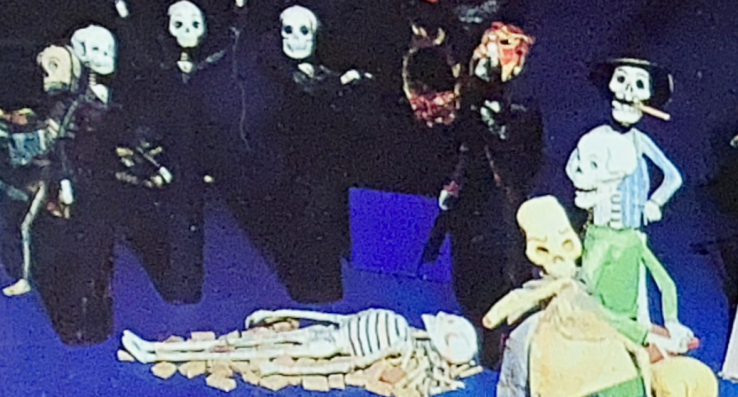

- The piece, according to the back of the postcard, is appropriately titled The Atomic Apocalypse—Will Death Die? The piece is a photograph of a painted papier mache menagerie, attirbuted to the Linares Family of Mexico City, 1989.

- Some old younger version of myself stuck it in the back of Riddley Walker as a joke.

- The postcard came from a man in Texas who won a contest to win a copy of the 25th-anniversary edition of Blood Meridian.

- This man sent several postcards, and I scanned them and shared them on the site, but this particular postcard is not in that set of shared postcards.

- Why? Did the postcard not fit on the scanner? Was it sent later, as a polite Thank you? (I don’t think so; on the postcard’s b-side, the man who won the contest shared a quote from Blood Meridian describing the physical appearance of Judge Holden.)

- Let this postcard stand as aesthetic précis for Riddley Walker though, and let me be done. (I will find the other postcards over the years, or not.)