Set millennia in the future, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 dystopian novel We tells the story of a man whose sense of self shatters when he realizes he can no longer conform to the ideology of his totalitarian government. Zamyatin’s novel is a zany, prescient, poetic tale about resisting the forces of tyranny, conformity, and brute, unimaginative groupthink.

We is narrated by D-503. D-503 is an engineer building a spacecraft, the Integral, which will expand the domain of OneState. Although OneState has conquered earth (after the apocalyptic Two Hundred Years War), they seek to expand their empire of conformity to the stars, perhaps replicating their giant city-state on planets yet unknown. In its physical form, OneState is a glass panopticon surrounded by a great Glass Wall that keeps the wild natural world out. In its ideological form, OneState mandates uniformity, mechanization, and mathematical precision. The denizens of OneState conform to this ideology at all times. They wear uniforms — “yunies” — that bear the numbers that serve as their names. Indeed, they are “Numbers,” not people. The Numbers wake and sleep at the exact same hour. They march in unison and live and work in glass buildings. They “vote” to elect the same Benefactor each year, who runs unchallenged. They eat foods made from petroleum and produce children in a machine-like process that follows a system of “Maternal and Paternal Norms.” Numbers that don’t meet these Norms are forbidden from reproducing, but any Number can register for intercourse with another Number on Sex Day. A secret police force, the Bureau of Guardians, monitors the population, but it’s ultimately groupthink that keeps the Numbers in line.

One-State’s groupthink ideology is neatly summed up in propaganda that D-503 shares late in the novel:

Here’s the headline that glowed from page one of the State Gazette:

REJOICE!

For henceforth you are perfect! Up until this day your offspring, the machines, were more perfect than you.

IN WHAT WAY?

Every spark of the dynamo is a spark of purest reason. Every stroke of the piston is an immaculate syllogism. But do you not also contain this same infallible reason? The philosophy of the cranes, the presses, and the pumps is as perfect and clear as a circle drawn with a compass. But is your philosophy any less perfect? The beauty of the mechanism is in the precise and invariable rhythm, like that of the pendulum. …But think of this: The mechanism has no imagination.

Imagination is the ultimate enemy of the machine, and the Benefactor and his Guardians have a plan to finally root it out and exterminate it.

Throughout much of We, D-503 is very much attuned to this ideology. D-503 thinks of OneState as “our glass paradise.” What we see as dystopia he sees as utopia, he initially constructs We as a testament to OneState’s glory that he will include as part of the cargo of the Integral. However, as the narrative unfolds, D-503 unravels. His sense of self divides as signs of mental illness emerge–first dreams, then an imagination, and then—gasp!—a soul.

D-503’s internal conflict stems from discovering his own innate irrationality—namely, a soul which cannot be measured in numbers or weighed in physical facts. This internal conflict drives much of the narrative of We. Zamyatin delivers this conflict in D-503’s first-person consciousness, a consciousnesses that contracts and expands, a consciousness that would love to elide its own first-person interiority completely and subsume itself wholly to a third-person we—but he can’t. Consider the following passage;

I lie in the bed thinking … and a logical chain, extraordinarily odd, starts unwinding itself.

For every equation, every formula in the superficial world, there is a corresponding curve or solid. For irrational formulas, for my √—1, we know of no corresponding solids, we’ve never seen them…. But that’s just the whole horror—that these solids, invisible, exist. They absolutely inescapably must exist. Because in mathematics their eccentric prickly shadows, the irrational formulas, parade in front of our eyes as if they were on a screen. And mathematics and death never make a mistake. And if we don’t see these solids in our surface world, there is for them, there inevitably must be, a whole immense world there, beneath the surface.

I jumped up without waiting for the bell and began to run around my room. My mathematics, up to now the only lasting and immovable island in my entire dislocated life, had also broken loose and floated whirling off. So does this mean that that stupid “soul” is just as real as my yuny, as my boots, even though I can’t see them now (they’re behind the mirror of the wardrobe door)? And if the boots are not a disease, why is the “soul” a disease?

What initiates D-503’s anti-quest for a soul? It is a woman of course. I-330 interrupts D-503’s routine life, puncturing his logic with irrational passions, taking him on transgressive trips to the Old House—and eventually, leading him to the greatest transgression of all. You see, there’s an underground movement, a secret resistance force—one that not uncoincidentally needs access to the Integral—and this resistance plans to…but I shouldn’t spoil more.

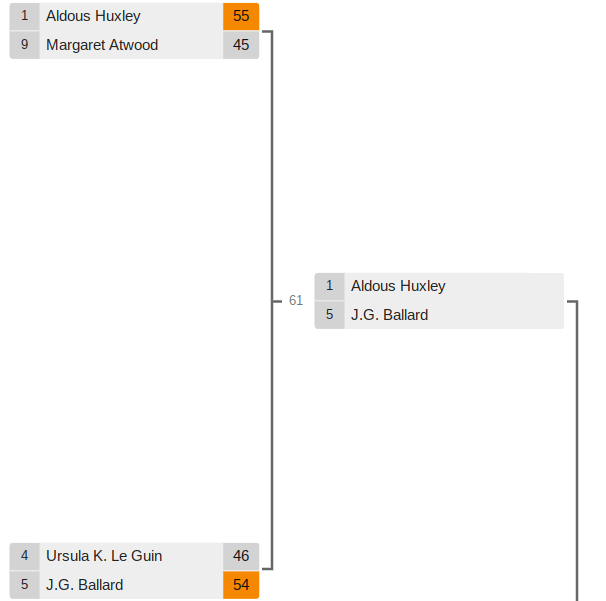

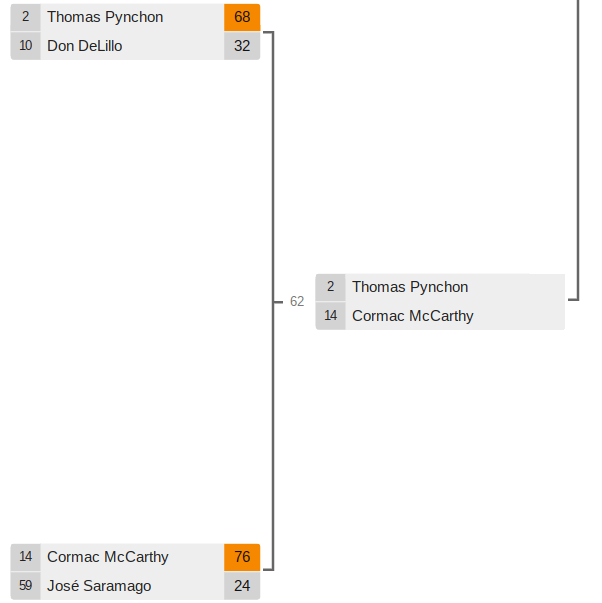

Or really, could I even spoil the plot of We? So many novels and films have borrowed heavily from (or at least echoed) its premise that you already know what it’s about. The major examples are easy—Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), Lang’s Metropolis (1927), Orwell’s 1984 (1949), Vonnegut’s Player Piano (1955), etc. Then there are all their followers—the cheap sci-fi paperbacks of the sixties and seventies, their corresponding films—Logan’s Run, Soylent Green–and so on and so on, well into our Now (Running Man, Total Recall, The Matrix, The Hunger Games, etc. forever).

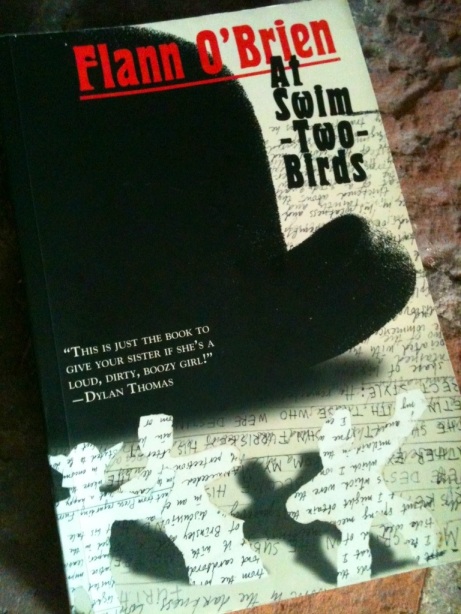

You get the point: We is a generative text. And after reading We, I couldn’t immediately think of a clear generative text that generated it. From what materials did Zamyatin craft his tale? The closest predecessor I could initially think of was Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1907), or maybe bits of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), neither of which feel as thoroughly modern as We does. However, cursory research (uh, skimming Wikipedia) turned up Jerome K. Jerome’s 1891 short story, “The New Utopia,” which does feature some of the tropes we find in We. Set in city of the future, “The New Utopia” features uniformed, nameless, numbered people whose government attempts to destroy the human imagination. Here, the “Destiny of Humanity” has become an egalitarian nightmare.

While it’s likely that “The New Utopia” furnished Zamyatin some of the tropes he needed to construct We, Jerome’s story simply doesn’t have the same epic themes of underground resistance to technological bureaucracy that have became the stock of so much 20th and 21st-century science fiction. (I rewatched Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) while reading We, and the parallels are remarkable—but the same can be said for any number of sci-fi films of the last sixty or so years).

More significantly, Jerome’s “The New Utopia” is beholden to a rhetorical scheme that makes it feel closer to an essay than a finished work of art. The story is essentially a one-sided dialogue—a man falls asleep, wakes up a few thousand years later, and gets the skinny on the utopian nightmare city he’s awoken in from an enthusiastic Future Person. Reading “The New Utopia” reminded me of reading London’s The Iron Heel, which essentially works in the same way—London’s plot often feels like an excuse to stitch together Marxist readings into monologues posing as dialogues.

Zamyatin’s book, in contrast, is Something New. We is a work of Modernism, not just a collection of new tropes, but a new configuration of those tropes. Zamyatin’s D-503 is a consciousness in crisis, a self that simultaneously dissovles and resolves into something new—a creature with a soul. Consider D-503’s recollection of a nightmare:

It’s night. Green, orange, blue; a red “royal” instrument; a yellow-orange dress. Then, a bronze Buddha; suddenly it raised its bronze eyelids and juice started to flow, juice out of the Buddha. Then out of the yellow dress, too: juice. Juices ran all over the mirror, and the bed began to ooze juice, and then it came from the children’s little beds, and now from me, too—some kind of fatally sweet horror….

The prose here showcases Zamyatin’s vivid style. We, crammed with colors, often evokes Expressionist and Futurist paintings. We get here a painterly depiction of D-503’s abjection, his sense of a self leaking out in “some kind of fatally sweet horror” — his boundaries overflowing. The dream-synthesis here is at once joyful, terrifying, and utterly bewildering to our poor hero. It is also poetic in his rendering. D-503 laments early in his narrative that he is not a poet so that he cannot properly celebrate OneState in writing for his readers. But later, his friend R-13—a poet himself—tells him that he has “no business being a mathematician. You’re a poet…a poet!”

R-13 is correct: D-503 is a poet, a poet who cannot abide all the metaphysics gumming up his mathematical mind. This poetry is rendered wonderfully in the English translation I read by Clarence Brown (1993), and is showcased in the very “titles” of each chapter (or “Record,” in the book’s terms). Each “Record” begins with phrases culled from the chapter. Here are a few at random:

An Author’s Duty

Swollen Ice

The Most Difficult Love

Through Glass

I Died

Hallways

Fog

Familiar “You”

An Absolutely Inane Occurrence

Letter

Membrane

Hairy Me

These are the titles of four random chapters, but I suppose we could string together the whole series and arrive at a Dadaist poem, one that might also serve as an oblique summary of We.

And yet for all its surrealist tinges and techno-dystopian themes, the poem that We most reminded me of was, quite unexpectedly, Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself (1855). Whitman’s poem sought a new language and a new form to tell the story of a new land, a new people. He wanted to be everyone and no one at the same time, himself a kosmos, form and void, an I, a you, a we. Whitman addressed his poem to both the you of his readership, an immortal future readership beyond him (“Listener up there!”) as well as himself, famously declaring: “I loaf and invite my soul.”

D-503 presents almost as an anti-Whitman. He directly addresses his “unknown readers” in nearly every chapter, and with a Whitmanesque turn, like this one: “You, my unknown readers, you will be told everything (right now you are just as dear, as close, and as unapproachable…).” His ebullience and optimism are ironic of course—they are honest performances that crack under the increasing reality of his emerging soul. Unlike Walt Whitman, D-503 cannot loaf and invite his soul. He can’t sustain the negative capabilities Whitman’s poem engenders. His we cannot reconcile with an I, even as it seeks a mediating you in its dear readers.

And yet for all its bitter ironies and for all its hero’s often feckless struggle, We is a comedy. The book is a cartoon-poem-satire, its comedy sustained in the careening voice of D-503. It’s somewhat well known that George Orwell used We as a template for 1984 (he began that novel less than a year after penning a review of a French translation of We). Orwell’s novel though falls into the same essaying that we see in The Iron Heel and “The New Utopia.” It’s also awfully dour. In contrast, We shuttles along with zany elan, inviting us to laugh at modern absurdity. Indeed, Zamyatin posits laughter as resistance to tyranny, myopia, and brutish closed-mindedness. Late in the novel, D-503 arrives at the following epiphany:

And that was when I learned from my own experience that a laugh can be a terrifying weapon. With a laugh you can kill even murder itself.

I could end by cataloging the various parallels that might be drawn between We and our own dystopian age, but I think that they are too obvious, and, as I’ve noted, have been repeated (with degrees of difference) throughout the body of dystopian narratives that We has helped generate. What the book does though—or I should say, what it did for me—is offer the strange comfort. A century after Zamyatin diagnosed the emergence of another modern world, the human position remains essentially unchanged, and in times of despair we can remember to laugh—and imagine to imagine. Very highly recommended.