William Melvin Kelley’s final novel Dunfords Travels Everywhere was published in 1970 to mixed reviews and then languished out of print for half a century. Formally and conceptually challenging, Dunfords contrasts strongly with the mannered modernism of Kelley’s first (and arguably most popular) novel A Different Drummer (1962). In A Different Drummer, Kelley offered the lucid yet Faulknerian tale of Caliban Tucker, a black Southerner who leads his people to freedom. The novel is naturalistic and ultimately optimistic. Kelley’s follow up, A Drop of Patience (1965), follows a similar naturalistic approach. By 1967 though, Kelley moved to a more radical style in his satire dem. In dem, Kelley enlarges his realism, injecting the novel with heavy doses of distortion. dem is angrier, more ironic and hyperbolic than the works that preceded it. Its structure is strange—not fragmented, exactly—but the narrative is parceled out in vignettes which the reader must synthesize himself. dem’s experimentation is understated, but its form—and its angry energy—point clearly towards Kelley’s most postmodern novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres. Polyglossic, fragmented, and bubbling with aporia, Dunfords, now in print again, will no doubt baffle, delight, and divide readers today the same way it did fifty years ago.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres opens in a fictional European city. A group of American travelers meet for a softball game, only to learn that their president has been assassinated. They head to a cafe to console themselves. After some wine, the Americans toast their fallen president and begin singing “one of the two or three songs the people back home considered patriotic.” Chig Dunford, the sole black member of the travelers, refrains from singing, and when his patriotism is questioned and he is implored to sing, he explodes: “No, motherfucker!” The profane outburst alienates his companions, and Chig questions his language: “Where on earth had those words come from? He tried always to choose his words with care, to hold back anger until he found the correct words.”

It turns out that Chig’s motherfucker is a secret spell, a compound streetword that unlocks the dreamlanguage of Dunfords Travels Everywheres. After its incantation, Dunfords’ rhetoric pivots:

Witches oneWay tspike Mr. Chigyle’s Languish, n curryng him back tRealty, recoremince wi hUnmisereaducation. Maya we now go on wi yReconstruction, Mr. Chuggle? Awick now? Goodd, a’god Moanng agen everybubbahs n babys among you, d’yonLadys in front who always come vear too, days ago, dhisMorning We wddeal, in dhis Sagmint of Lecturian Angleash 161, w’all the daisiastrous effects, the foxnoxious bland of stimili, the infortunelessnesses of circusdances which weak to worsen the phistorystematical intrafricanical firmly structure of our distinct coresins: The Blafringro‐Arumericans.

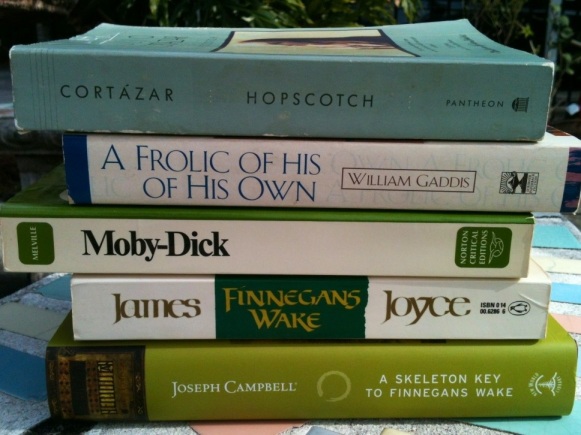

So Chig, who has told us he looks always to choose the “correct words,” comes through languish/language “back tRealty,” to commence again his education and reconstruction. He’s given new names Mr. Chuggle and Mr. Chigyle. Renaming becomes a motif in the novel. Here in the dreamworld—or is it reality, as Chig’s dreamteachers seem to suggest?—there are multiple Chigs, a plot point emphasized in the novel’s strange title. Dunfords Travels Everwheres seems initially ungrammatical—shouldn’t the title be something like Dunford Travels Everywhere or Dunford’s Travels Everywhere? one wonders at first. Packed into the title though is a key to the novel’s meaning: There are multiple Dunfords, multiple travels, and, perhaps most significantly, multiple everywheres. The novel’s title also points to two of its reference points, Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (famously absent an apostrophe).

Many readers will undoubtedly recognize the influence of Joyce’s Wake in Kelley’s so-called experimental passages. And while Finnegans is clearly an inspiration, Kelley’s prose has a different flavor—more creole, more pidgin, more Afrocentric than Joyce’s synthesis of European tongues. The passages can be difficult if you want them to be, or you can simply float along with them. I found myself reading them aloud, letting my ear make connections that my eyes might have missed. I’ll also readily concede that there’s a ton of stuff in the passages that I found inscrutable. Sometimes its best to go with the flow.

And where does that flow go? The title promises everywheres, and the central plot of Dunfords might best be understood as a consciousness traveling though an infinite but subtly shifting loop. Chig Dunford slips in and out of the dreamworld, traveling through Europe and then back to America. The final third of the novel is a surreal transatlantic sea voyage that darkly mirrors the Euro-American slave trade. It’s also a shocking parody of America’s sexual and racial hang-ups. It’s also really confusing at times, calling into question what elements of the book are “real” and what elements are “dream.” In my estimation though, the distinction doesn’t matter in Dunfords. All that matters is the language.

The language—specifically the so-called experimental language—transports characters and readers alike. We’re first absorbed into the dreamlanguage on page fifty, and swirl around in it for a dozen more pages before arriving somewhere far, far away from Chig Dunford in the European cafe. In the course of a paragraph, the narrative moves from linguistic surrealism to lucid realism to start a new thread in the novel:

Now will ox you, Mr. Chirlyle? Be your satisfreed from the dimage of the Muffitoy? Heave you learned your caughtomkidsm? Can we send you out on your hownor? Passable. But proveably not yetso tokentinue the candsolidation of the initiatory natsure of your helotionary sexperience, le we smiuve for illustration of chiltural rackage on the cause of a Hardlim denteeth who had stopped loving his wife. Before he stopped loving her, he had given her a wonderful wardrobe, a brownstone on the Hill, and a cottage on Long Island. Unfortunately, her appetite remained unappeased. She wanted one more thing—a cruise around the world. And so he asked her for a divorce.

This Harlem dentist employs Carlyle Bedlow, a minor but important character in dem, to seduce his wife. Bedlow then becomes a kind of twin to Chig, as the novel shifts between Chig’s story and Bedlow’s, always mediated via dreamlanguage. Bedlow’s adventures are somewhat more comical than Chig’s (he even outfoxes the Devil), and although he’s rooted in Harlem, he’s just as much an alien to his own country as Chig is.

Dunfords’ so-called experimental passages are a linguistic bid to overcome that alienation. While they clearly recall the language of Finnegans Wake, they also point to another of Joyce’s novels, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Kelley pulls the first of Dunfords’ three epigraphs from Joyce’s novel:

The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine…I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech…My soul frets in the shadow of his language.

In Portrait, Stephen Dedalus realizes that he is linguistically inscribed in a conqueror’s tongue, but he will work to forge that language into something capable of expressing the “uncreated conscience of [his] race.” The linguistic play of Dunfords finds Kelley forging his own language, his own tongue of resistance.

The dreamlanguage overtakes the final pages of Dunfords, melting African folklore with Norse myths into something wholly new, sticky, rich. There’s more than a dissertation’s worth of parsing in those last fifteen pages. I missed in them than I caught, but I don’t mind being baffled, especially when the book’s final paragraph is so lovely:

You got aLearn whow you talking n when tsay whit, man. What, man? No, man. Soaree! Yes sayd dIt t’me too thlow. Oilready I vbegin tshift m Voyace. But you llbob bub aGain. We cdntlet aHabbub dfifd on Fur ever, only fo waTerm aTime tpickcip dSpyrate by pinchng dSkein. In Side, out! Good-bye, man: Good-buy, man. Go odd-buy Man. Go Wood, buy Man. Gold buy Man. MAN!BE!GOLD!BE!

You’ve got to learn how/who you are talking to and when to say what/wit, right? The line “Oilready I vbegin tshift m Voyace” points to shifting voices, shifting consciousnesses , but also the voice as the voyage, the tongue as a traveler.

The passages I’ve shared above should give you a sense of whether or not the ludic prose of Dunfords is your particular flavor of choice. Initial reviews were critical of Kelley’s choices, including both the novel’s language and its structure. It received two contemporary reviews in The New York Times; in the first, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt praised Kelley’s use of “a black form of the dreamlanguage of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake…to escape the strictures of the conventional (white) novel,” but concluded that “there are many things in the novel that don’t work, that seem curiously cryptic and incomplete.” Playwright Clifford Mason was far harsher in his review a few weeks later, writing that “the experimental passages offer little to justify the effort needed to decipher them. The endless little word games can only be called tiresome.”

I did not find the word games endless, little, or tiring, but I’m sure there are many folks who would agree with Mason’s sentiments from five decades ago. While American culture has slowly been catching up to Kelley’s politics and aesthetics, his dreamlanguage will no doubt alienate many contemporary readers who prefer their prose hardened into lucid meaning. Kelley understood the power of language shift. He coined the word “woke” in a 1962 New York Times piece that both lamented and celebrated the way that black language was appropriated by white folks only to be reinvented again by by black speakers. In some ways, Dunfords is his push into a language so woke it appears to be the language of sleep. But the subconscious talkers in Dunfords don’t babble. Their words pack—perhaps overpack—meaning.

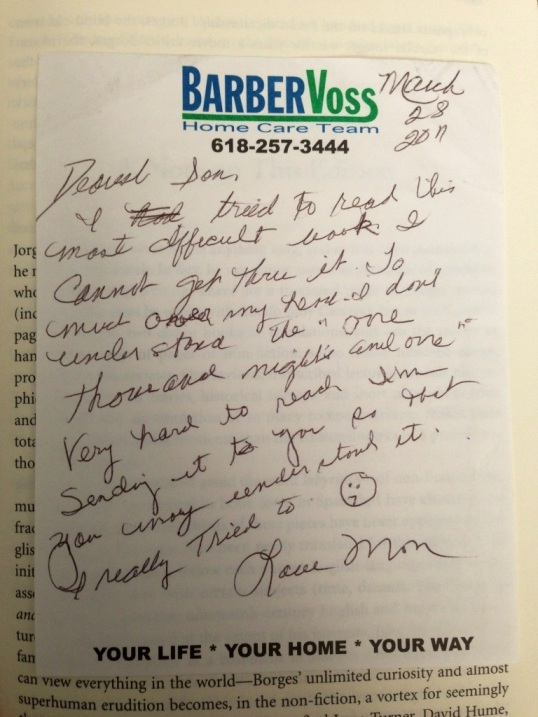

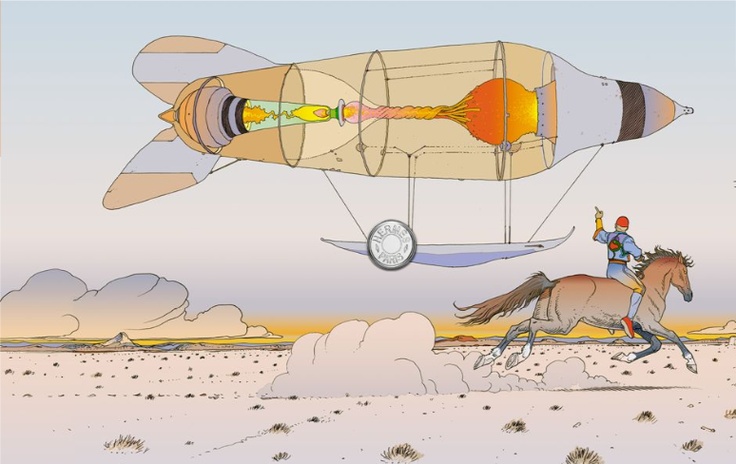

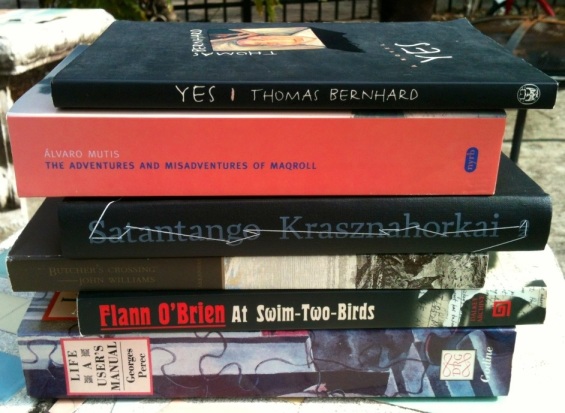

The overpacking makes for a difficult read at times. Readers interested in Kelley—an overlooked writer, for sure—might do better to start with A Different Drummer or dem, both of which are more conventional, both in prose and plot. Thankfully, Anchor Books has reprinted all five of Kelley’s books, each with new covers by Kelley’s daughter. This new edition of Dunfords also features pen-and-ink illustrations that Kelley commissioned from his wife Aiki. These illustrations, which were not included in the novel’s first edition in 1970, add to the novel’s surreal energy. I’ve included a few in this review.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres is a challenging, rich, weird read. At times baffling, it’s never boring. Those who elect to read it should go with the flow and resist trying to impose their own logical or rhetorical schemes on the narrative. It’s a fantastic voyage—or Voyace?—check it out.