Have you read Honoré de Balzac’s 1833 novel Eugénie Grandet?

I haven’t, but I’ve read the Wikipedia summary.

I’ve also read, several times, Donald Barthelme’s 1968 parody, “Eugénie Grandet,” which is very very funny.

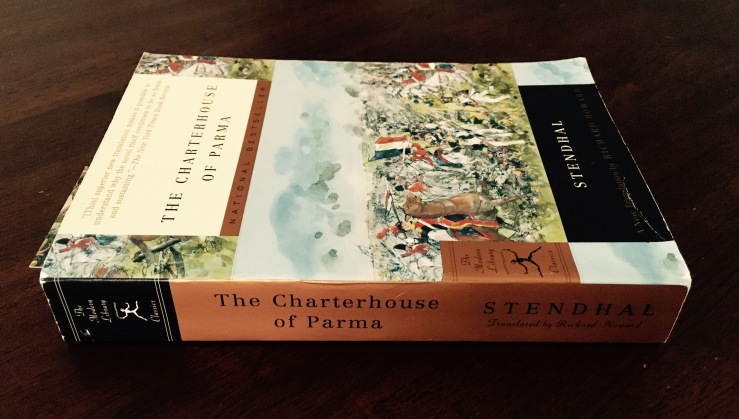

Have you read Stendhal’s 1839 novel The Charterhouse of Parma?

After repeated false starts, I seem to be finishing it up (I’m on Chapter 19 of 28 of Richard Howard’s 1999 Modern Library translation).

I brought up Eugénie Grandet (Balzac’s) to bring up “Eugénie Grandet” (Barthelme’s). Stendhal’s (1830’s French) novel Charterhouse keeps reminding me of Barthelme’s (1960’s American) short story “Eugénie Grandet,” which is, as I’ve said, a parody of Honoré de Balzac’s (1830’s French) novel Eugénie Grandet. Balzac and Stendhal are pre-Modernists (which is to say they were modernists, I suppose). Donald Barthelme wanted to be a big em Modernist; his postmodernism was inadvertent. By which I mean— “postmodernism” is just a description (a description of a description really, but let me not navelgaze).

Well and so: I find myself often bored with The Charterhouse of Parma and wishing for a condensation, for a Donald Barthelme number that will magically boil down all its best bits into a loving parody that retains its themes and storylines (while simultaneously critiquing them)—a parody served with an au jus of the novel’s rich flavor.

My frequent boredom with the novel—and, let me insert here, betwixt beloved dashes, that one of my (many) favorite things about Charterhouse is that it is about boredom! that phrases like “boredom,” boring,” and “bored” repeat repeatedly throughout it! I fucking love that! And Stendhal, the pre-Modernist (which is to say “modernist”), wants the reader to feel some of the boredom of court intrigue (which is not always intriguing). The marvelous ironic earnest narrator so frequently frequents phrases like, “The reader will no doubt tire of this conversation, which went on for like two fucking hours” (not a direct quote, although the word “fuck” shows up a few times in Howard’s translation. How fucking Modern!)—okay—

My frequent boredom with the novel is actually not so frequent. It’s more like a chapter to chapter affair. I love pretty much every moment that Stendhal keeps the lens on his naive hero, the intrepid nobleman Fabrizio del Dongo. In love with (the idea of) Napoleon (and his aunt, sorta), a revolutionist (not really), a big ell Liberal (nope), Fabrizio is a charismatic (and callow) hero, and his chapters shuttle along with marvelous quixotic ironic energy. It’s picaresque stuff. (Fabrizio reminds me of another hero I love, Candide). Fabrizio runs away from home to join Napoleon’s army! Fabrizio is threatened with arrest! Fabrizio is sorta exiled! Fabrizio fucks around in Naples! Fabrizio joins the priesthood! Fabrizio might love love his aunt! Fabrizio fights a duel! Fabrizio kills a man! (Not the duel dude). Fabrizio is on the run (again)! Fabrizio goes to jail! Fabrizio falls in love!

When it’s not doing the picaresque adventure story/quixotic romance thing (which is to say, like half the time) Charterhouse is a novel of courtly intrigues and political machinations (I think our boy Balzac called it the new The Prince). One of the greatest strengths of Charterhouse is its depictions of psychology, or consciousness-in-motion (which is to say Modernism, (or pre-modernism)). Stendhal takes us through his characters’ thinking…but that can sometimes be dull, I’ll admit. (Except when it’s not). Let me turn over this riff to Italo Calvino, briefly, who clearly does not think the novel dull, ever—but I like his description here of the books operatic “dramatic centre.” From his essay “Guide for New Readers of Stendhal’s Charterhouse“:

All this in the petty world of court and society intrigue, between a prince haunted by fear for having hanged two patriots and the ‘fiscal général’ (justice minister) Rassi who is the incarnation (perhaps for the first time in a character in a novel) of a bureaucratic mediocrity which also has something terrifying in it. And here the conflict is, in line with Stendhal’s intentions, between this image of the backward Europe of Metternich and the absolute nature of those passions which brook no bounds and which were the last refuge for the noble ideals of an age that had been overcome.

The dramatic centre of the book is like an opera (and opera had been the first medium which had helped the music-mad Stendhal to understand Italy) but in The Charterhouse the atmosphere (luckily) is not that of tragic opera but rather (as Paul Valéry discovered) of operetta. The tyrannical rule is squalid but hesitant and clumsy (much worse had really taken place at Modena) and the passions are powerful but work by a rather basic mechanism. (Just one character, Count Mosca, possesses any psychological complexity, a calculating character but one who is also desperate, possessive and nihilistic.)

I disagree with Calvino here. Mosca is an interesting character (at times), but hardly the only one with any psychological complexity. Stendhal is always showing us the gears ticking clicking wheeling churning in his characters’ minds—Fabrizio’s Auntie Gina in particular. (Ahem. Excuse me–The Duchessa).

But Duchess Aunt Gina is a big character, perhaps the secret star of Charterhouse, really, and I’m getting read to wrap this thing up. So I’ll offer a brief example rather from (what I assume is ultimately) a minor character, sweet Clélia Conti. Here she is, in the chapter I finished today, puzzling through the puzzle of fickle Fabrizio, who’s imprisoned in her dad’s tower and has fallen for her:

Fabrizio was fickle; in Naples, he had had the reputation of charming mistresses quite readily. Despite all the reserve imposed upon the role of a young lady, ever since she had become a Canoness and had gone to court, Clélia, without ever asking questions but by listening attentively, had managed to learn the reputations of the young men who had, one after the next, sought her hand in marriage; well then, Fabrizio, compared to all the others, was the one who was least trustworthy in affairs of the heart. He was in prison, he was bored, he paid court to the one woman he could speak to—what could be simpler? What, indeed, more common? And this is what plunged Clélia into despair.

Clélia’s despair is earned; her introspection is adroit (even as it is tender). Perhaps the wonderful trick of Charterhouse is that Stendhal shows us a Fabrizio who cannot see (that he cannot see) that he is fickle, that Clélia’s take on his character is probably accurate—he’s just bored! (Again, I’ve not read to the end). Yes: What, indeed, could be more common? And one of my favorite things about Charterhouse is not just that our dear narrator renders that (common) despair in real and emotional and psychological (which is to say, um Modern) terms for us—but also that our narrator takes a sweetly ironic tone about the whole business.

Or maybe it’s not sweetly ironic—but I wouldn’t know. I have to read it post-Barthelme, through a post-postmodern lens. I’m not otherwise equipped.